11th June 2009

A review of Jaron Lanier’s Who Owns the Future?

What becomes of America when the social contract can no longer be fulfilled? Generations of parents taught their children about deals that they thought were immutable aspects of the American condition; they now watch their adult children struggle in a society where those deals are not honored. The current employment crisis in the U.S. can be understood only in light of this basic social contract, the central theme of the American myth, the moral of our national fable: If you work, you will survive. Not only will you survive but you will prosper. All our propaganda begins here. Young Americans are promised that work will translate to an ever-improving lot in life, within and across generations — a bigger house when you’re 40, and your children in a bigger house than they were raised in. You might say that this is a lot to ask of any social order. But then, it wasn’t my idea.

A country that has made its self-definition utterly dependent on the ubiquity of paying work now has an insufficient number of jobs. This is not short-term economic cyclicality; labor-force participation has dropped, fairly steadily, for decades. Capital-biased technological change contracts industry after industry. The most powerful, most profitable companies now employ a tiny fraction of the workers that similarly sized enterprises once did. The biggest employers, like Wal-Mart, provide insufficient wages and hours to give employees access to middle-class existence. The problem is not merely those who are entirely unemployed but also those who need more hours or higher wages and can’t get them. And all these people desperate to work or for more work undermine the bargaining power of those currently employed. Who asks for a raise when there are 50,000 young graduates who will do your job for two-thirds of what you make now? Who complains about discrimination, harassment, and other workplace immiseration when relief for employers is a round of pink slips away? This is what an employment crisis means. The unemployed suffer, and their suffering causes the employed to suffer. Each person’s precarity is instrumental in another’s.

It is hard to overstate: This country, in its current condition, has no other option but something close to full employment. Our pathetic social safety net, even absent the contracting effect of austerity measures, can’t fill in the gaps caused by the demise of ubiquitous employment. Even the counterrevolution has no other idiom; the most common epithet directed toward Occupy protests, after all, was “Get a job!” That the near impossibility of getting a job was the point for many who were protesting was too destabilizing a notion to be understood. In the short term, I have no doubt that the unemployment rate will fall. The question is the long-term structural dependability of a social contract built on mass employment.

***

For argument’s sake, let’s consider America’s employment crisis not as a failure of conservatism, market fundamentalism, neoliberalism, nor austerity. Let’s suppose that the problem is proceduralism.

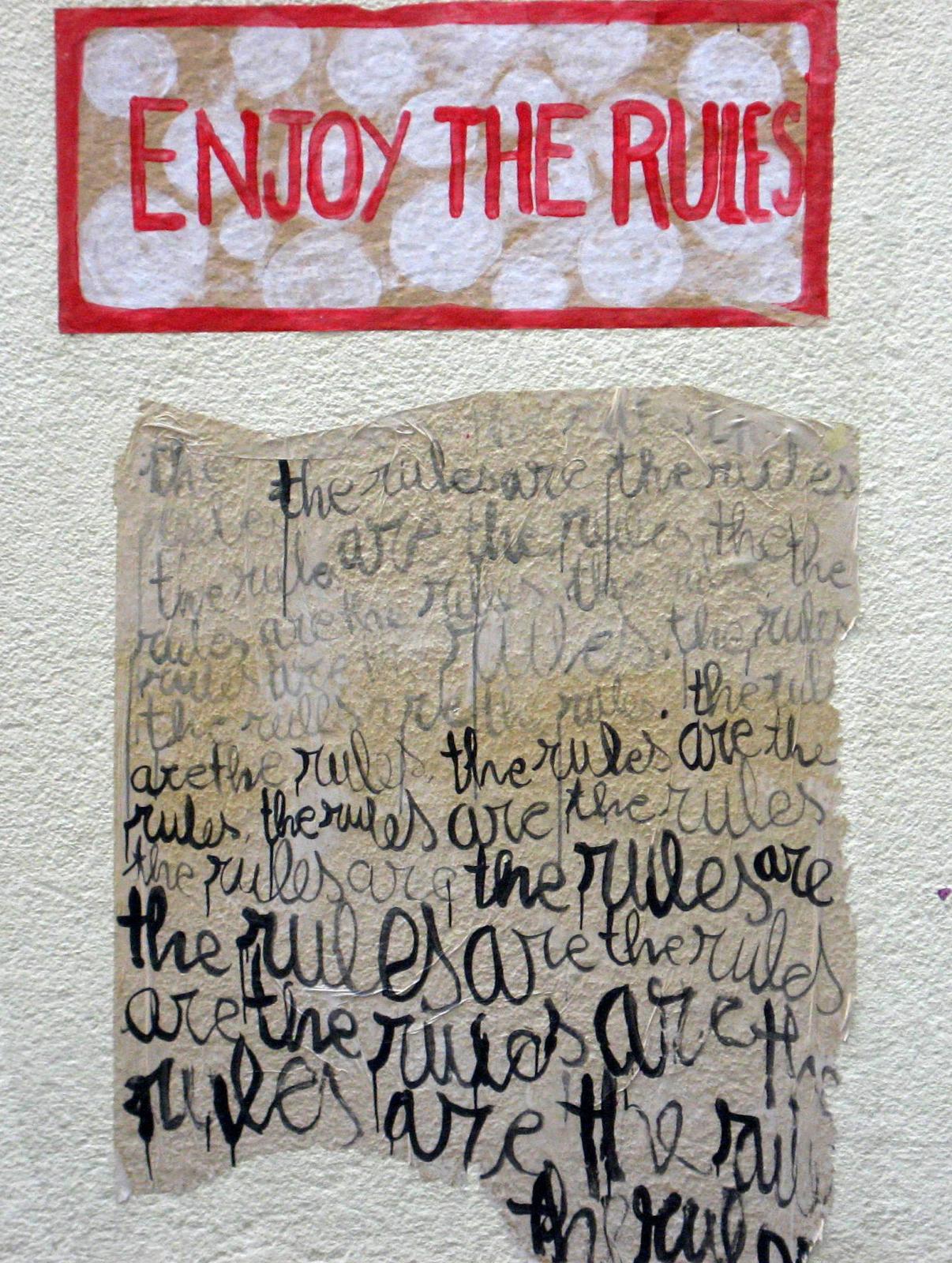

A proceduralist views society not in terms of a necessary goal (say, happiness and opportunity for all its members) but instead as a set of rules that it must follow—because they are natural, because they stem from the Western tradition, because they comport with human behavior, because they follow God’s law, depending on whoever is justifying the current procedure. If these rules are followed, no injustice needs to be redressed. Rules can be discarded or changed if their intent is found to be problematic, but outcomes can be good or bad without issue. Problems arise only if the rules are broken.

Proceduralism tends to be popular among those who wrote the procedures; it’s a discourse of power. From Wall Street to the NSA, “we were following the rules” is a cynical but effective defense, undertaken by people who know that those same rules will save them from the consequences of their destructive yet superficially lawful behavior.

But what happens when established procedures lead to unsustainable or immoral consequences, such as widespread and persistent unemployment? The employment crisis reveals a conflict between the procedures of democratic capitalism, which ensure certain rights but promise nothing else, and the logic of the American social contract, which justifies the social order by assuring citizens that they can trade work for material security.

Talk of social contracts is passé in an America obsessed with technocapitalist visions of a prosperous future. The yen for “disruption,” an empty term for empty minds in empty people, makes traditional obstacles like social contracts suspect or downright pernicious. This has led to an embrace of proceduralism by those true believers who want an app economy to be the engine of capitalism. And such people rule the world.

The problem for proceduralists is that social contracts exist for a reason. It turns out that there are, actually, certain outcomes that society must ensure if it is to go on functioning. The really essential function of the social contract is to prevent the people from burning everything down. There are too many of us to be held down by force. The average person must agree to be governed for anything resembling civilization to endure. If the average citizen finds that their agreement with society has been broken, then civil unrest will result, as it has in Egypt, and in Greece, and in Turkey, and in Brazil. Trust me: it is not the cops that keep people from invading your home and stealing your stuff. Proceduralists may generally rule, but eventually, their bodies end up stacked in the village square.

Reactionaries of various stripes respond that something, somehow, will come along, despite the fact that recent Stanford graduates, pockets stuffed with Silicon Valley cash, are creatively disrupting the jobs out from under hundreds of thousands of Americans. The economy will correct itself, jobs will spontaneously will themselves into being, just as the finance industry will become spontaneously, magically self-regulating.We just need everybody to buy into the rules, to accept the procedure..

For the rest of us who have lost faith in these rules, the question is what else is to be done. Can full employment be brought back by force? Can something else be built in its place? These are uncomfortable questions in a proceduralist country populated by a teleological people. But they are not going away. In his latest book, Who Owns the Future?, Jaron Lanier tries to provide some answers.

***

The growing edifice of tech journalism is dominated by a certain kind of thinking: optimistic to the point of triumphalist, obsessed with gadgetry, endlessly impressed by technological legerdemain, stuffed with faith in capitalism, delighted by empty buzzwords and facile grand narratives, always enraptured by the next hot gizmo but endlessly impatient for the next big thing. There is never a shortage of complaints — why has someone not innovated those grubby delivery men out of pizza delivery yet? But salvation is always only a few drops of innovation away. What kind of problems do you have? Tech is coming. Poverty, disease, war, rape? Hey, man. Just wait for 3-D printers.

Lanier has, for decades, represented an alternative: the humanist techie. Immune to the accusation of being a Luddite, Lanier has legitimacy to burn among technologists. A pioneer in virtual reality, his pedigree goes back to the earliest days of a recognizable Silicon Valley. He has seen transformative technologies from their earlier days and refuses to take them for granted. At MIT, at Xerox labs, at Marvin Minsky’s cluttered apartment — he was there. Lanier has that rare ability to mention an association with big name after big name without ever seeming pretentious. That’s due in part to his principled insistence on giving credit where due — an instinct that underlies the big answer his book proposes to preserve the middle class.

But his love for technology does not imply the kind of solipsism and sloppiness that mark many technology writers. In attacking digital optimism, Lanier makes for a compelling apostate. Against those who mistake technology for an agent of change, rather than a tool through which human beings create change, Lanier can be unsparing. The clarity of his thinking helps demonstrate the wooly illogic of various utopian assumptions, the folly of thinking that the Internet means we can have something for nothing — that we can freely download anything and everything without incurring a social cost.

Anyone who has ever publicly questioned the long-term sustainability or morality of digital piracy (or “piracy,” if you prefer) knows how quickly the mob will descend on you. To insist that people who create digitizable goods should be compensated is to be seen as a rube, an authoritarian, an apologist for the Man. Yet Lanier is unflinching: the endless copying and sharing of worthwhile digital media has deeply threatened creative industries and may threaten the essential structure of civil society by undermining the economics behind middle-class jobs.

In his first book, You Are Not a Gadget, Lanier (an accomplished musician) describes the way in which file sharing has gutted the “musical middle class.” The magical thinking which pervades justification for endless digital copying has provided no answers to the vast decline in revenues for music. Despite the anti-elite posturing that has long attended pro-piracy arguments, the elites in the music business are doing fine. Jay-Z can continue to make his millions selling cell phones and T-shirts. It’s the musical middle class, people who clawed their way to sustainable employment in the arts in jobs as session musicians or A&R guys or similar, who have lost the most. People may have thought that they were merely robbing from the rich when they used file sharing services, but last time I checked, the guys in Metallica were still millionaires.

There were legitimate complaints, in the early years of file sharing, that there were no practical, legal alternatives that permitted consumers to purchase digital content. Those complaints can no longer be taken seriously. Now, it’s easy to get songs for 89 cents, albums for $5, 48-hour movie rentals for $2, endless apps for a couple bucks, access to Netflix’s vast streaming database for less than $10 a month…. Yet unauthorized and unpaid downloads continue to number in the hundreds of millions. Can it really be that less than $10 a month is still too much for access to so much content? How low, exactly, must the price point be before there is no longer a legitimate excuse for not paying it? What if that price can’t sustain the people who create the content?

People are still getting paid, with digital file sharing—the search engines that direct you to the files, the programs that enable the downloads, the ISPs that provide the bandwidth, the electric companies that power the computer. But among these winners, Lanier’s chief targets in Who Owns the Future? are what he calls the “Siren Servers,” which capture vast amounts of value that was once more evenly distributed throughout the economy, partly by preying on the willingness of many millions of people to provide content for free (or “free,” in his telling).

Lanier’s question is whether large masses of people deserve to somehow share in that value more broadly, given that it derives from their effort. It’s by now a well-worn cliché that Facebook’s hundreds of millions of users are not its customers but rather its product, a giant focus group that provides corporations with fine-grained data to parse and eyeballs for advertising. For individual Facebook users, the deal seems all right: a full-featured suite of social networking and data-hosting features at the cost of giving your data to strangers. Whether it works for society is a different question: The market value that siren servers create inevitably accrues to capital-intensive but low-employee companies, linking innovation to job destruction.

In excerpts and interviews, Lanier has talked about the demise of Kodak and the rise of Instagram. Both represent large corporate entities in terms of market value, customers, and visibility. But Kodak employed many thousands; Instagram, a few dozen. Many have rejected or even mocked this comparison: “They aren’t really the same kind of company!” But that’s an example of proceduralist myopia. Lanier’s point is not that these companies are perfect analogues but to note the trend in companies’ revenue-to-employee ratio. You could even compare completely dissimilar services, if you’d like, such as GM to Google. The automaker employed a generation of blue-collar workers and provided the means for a middle-class existence. Google, by its nature, never will.

Part of Lanier’s strength is in showing how this loss of value can spread from media businesses to other industries. Arts and media are not typically seen as being a part of the mainstream, middle American economy. But a vast number of industries are going to be subject to the disruption that has become the norm in media. In 50 years, there will be no such thing as a cabbie. The steady job that offered stable wages to thousands of new immigrants in urban locales will be gone. Bank tellers and nurses and elementary school teachers and journalists aren’t safe, either. For years, medicine has been trumpeted as a safe haven from unemployment. But the high-price of health care may drive the development of technological substitutes. Are doctors and nurse’s aides going to be replaced by robots in the next 50 years? I don’t know, but to not worry about it—to continue to push more and more young graduates into the medical field out of a conviction that it represents a safe harbor? That just seems foolish and potentially cruel.

***

One of Lanier’s cherished metaphors is his notion of “levees.” Levees, in Lanier’s text, are systems that ensure middle-class stability against the degradations of day-to-day capitalist chaos. Levees include systems like unions and hack licenses for cabbies. It’s an intuitively compelling metaphor on its own, and Lanier is perfectly right about the now-degraded ability of certain social structures to empower a middle class against income inequality. But he embeds this specific metaphor in a chapters-long conceit about how capitalism is like water, and the flow of this water resembles income distribution charts. He overdoes the comparison, to the point where its basic purpose is degraded. That section includes lines like “A mountain of [levees] rising in the middle of the economy might be visualized as a mountain of rice paddies…. Such a mountain rising in the sea of the economy creates a prosperous island in the tempest of capital.” The caption to an illustration: “An ad hoc mountain of rice-paddy-like levees raises a middle class out of the flow of capital that would otherwise tend toward the extremes of a long tail of poverty (the ocean to the left) and an elite peak of wealth (the waterfall/geyser in the upper right corner. Democracy depends on the mountain being able to outspend the geyser.” Whether you’re looking at the illustration or not, this makes no sense.

Many high school writers look at commas like a spice that you must arbitrarily sprinkle over your words to make a piece of writing come out right. Lanier has a similar taste for metaphor. For those who are unwilling to learn the technical details of the protocols and languages that permit our connected lives, like TCP/IP, metaphor is necessary. But Lanier lets his love for metaphor get away from him. When his metaphors work, they are intelligent and cutting. When they don’t, they fail on an elementary level.

Consider this extended metaphor that’s sprinkled out over a few pages in the book’s long descriptive section.

You may think of a marketplace as a form of what’s called an optimization problem….

Check.

Suppose you have a shower with only hot and cold knobs….

All right.

There are two inputs, hot and cold. A market can be thought of as a similar system, but with many inputs….

Okay.

The hot and cold knobs can be thought of like the X and Y directions on graph paper.

Well, all right.

Now set a piece of imaginary graph paper down on an imaginary desk in your mind. Imagine that each point on the graph paper sprouts a pole that sticks up….

Uh-huh.

A forest of these poles will form a sculpture above the graph paper….

I see.

This is also how evolution works….

Is it?

The idea of a marketplace is similar to evolution….

A-ha.

A multitude of businesses coexist in a market, each like a species, or a mountaineer on an imaginary landscape, each trying different routes.

So to clarify: Markets are like a shower with hot and cold knobs, which are like the X and Y dimensions on graph paper, which rests on an imaginary desk, from which extends poles, which resemble a forest, which forms a sculpture, which is like evolution, which brings us back to a marketplace, which is like mountaineering. It will not surprise you to learn that this conceit is extended to include cloud computing and artificial intelligence. I tell you truthfully: I don’t know if I’m too dumb to follow this or too smart. Either way, it’s beyond me.

Sometimes his metaphors aren’t elaborate so much as incomplete. Consider the following passage.

Every tale of adventure lately seems to include a scene in which characters are attempting to crack the security of someone else’s computer. That’s the popular image of how power games are played out in the digital age, but such ‘cracking’ is only a tactic, not a strategy. The big game is the race to create ascendant Siren Servers….

It’s like the setup to a joke without the punch line. How does computer cracking from James Bond movies relate to people trying to create a new Facebook? Where’s the second half of the metaphor?

Examples such as these are indicative of a writer so habituated to metaphorizing that he doesn’t bother to think them through. Lanier’s strengths — his tendency to assimilate an eagle’s-eye view of broad movements and his talent for aphorism — make this type of off-handed analogizing irresistible.

This a genuine shame, as Lanier can be cutting when he chooses to be. Reflecting on the absurd utopianism that occurs when the technological imagination comes unmoored from reality, he writes, “computer scientists are human, and are as terrified by the human condition as anyone else.” This is no-bullshit insight, animated by experience and expressed by someone with the credibility to say it. It requires no convoluted imagery to be understood.

But it may be the flaws of his convoluted, analogistic style necessarily mirror the solution he is trying to express. It is complex, idealistic, intriguing, ambitious, admirable though flawed, and utterly unworkable.

His solution is, essentially, to rewind the Internet, and reverse a decision he considers momentous and destructive. For Lanier, the fundamental flaw of the Internet is that its links are not two-way—that is, by default, a link leads forward to another page, but that page does not by default contain a link back to pages that link to it. What Lanier laments is that linkbacks, trackbacks, pingbacks, and similar are not embedded in the basic technological architecture of the internet.

Two-way linking, Lanier argues, would be a key instrument of reciprocity on the Web, fostering a culture of mutually beneficial cooperation and due credit. Lanier, walking the talk, traces his idea to Ted Nelson, a network theorist who envisioned something like the Internet before it existed. The essence of network life would be linking reciprocity, Nelson believed, because only this made networking fair for all participants.

Having perceiving the inadequate distribution of wealth our digital networks have fostered, Lanier dreams of an Internet where not only are links reciprocal but so is wealth generation. In the (overlong) last section of Who Owns the Future? Lanier describes his proposal for introducing this sort of reciprocity, a system wherein micropayments are constantly shuffled between online participants as each uses another’s data. The point is to cut people who aren’t holding stock in Google in on the action. The network would have embedded within it a financial transfer system that remunerated people for their data, whether personal or creative or annotative. Two-way linking, married to a system of automatic micropayments, makes this possible. “If the system remembers where information originally comes from,” Lanier writes, “then the people who are the sources of information can be paid for it.”

Today’s pure amateurs, who never derive any money from online interactions — which must describe the large majority of internet users — would in Lanier’s system be eligible to earn when they, say, logged onto Facebook or posted to YouTube. The more views, the higher the payment. Whenever a company scrapes users’ data, the users would be remunerated, depending on how much it is used. Meanwhile, as these users read blog posts or view videos, they would automatically pay for it, though some of that cost would be subsidized through advertising and through the value that flows to them when their data is scraped by Google Analytics.

Lanier’s system is not intended at all to be revenue-neutral for individuals. A blogger who regularly pumps out content and delivers value to many people would see a net gain — as will someone who makes memes that are shared by thousands or instructions for building a deck that benefits many, and so on. For some, this value will be sufficient to live on. Others, who have conventional jobs and income, will be net spenders, sending out more money for watching cat videos and downloading guitar tabs and streaming porn than they take in for the data and content they produce.

Lanier’s plan is at once intuitively satisfying and hard to wrap your mind around. This summary does not do justice to the scope of his dreams. His exploration of all that his system would entail ranges from the grand to the minute, from the purely practical to the fanciful. Some reviewers have complained that his system’s many implausibilties — technological implausibility, legal implausibility, cultural implausibility — makes this level of detail self-indulgent. But more relevant than whether his dream is plausible is what kind of revolutions Lanier is willing to dream about, and what kinds he isn’t.

The basic notion of cutting people into the system through which their data and online activity are monetized is compelling. What’s less clear is if this can happen on anything like the scale necessary for replacing the middle-class jobs that are disappearing. Lanier is convinced that if we actually monetized all the value that we derive from interacting with each other online, it would represent a vast fortune that could be divided fairly. “Twitter doesn’t yet know how to make much money, for instance,” Lanier writes,

but is defended this way: "Look at all the value it is creating off the books by connecting people better!" Yes, let’s look at that value. It is real, and if we want to have a growing information-based economy, the real value ought to be part of our economy. Why is it suddenly a service to capitalism to keep more and more value off the books?

I agree: That value is real. My question is whether it can replace manufacturing, the auto industry, and all the other industries that no longer employ people in the numbers or at the relative wages they once did. The math is everything.

It’s important to point out that not everyone spends endless time creating and extracting value from the Internet. Lanier’s book is guilty of a common sin in contemporary commentary: It assumes that everyone is or wants to be an Internet obsessive in the way the book’s audience (and this review’s probable audience) is. Participation on the internet — and the way it is economically valued — is still broadly influenced by socioeconomic class, education, and age. Perhaps that will change, but what happens to the people whose jobs are gradually disappearing who don’t have the time, ability, or inclination to be constantly trading value online?

This silence on class difference speaks to the book’s most consistent, most aggravating flaw. Lanier is a liberal and, as such, betrays a liberal’s limited imagination. As the passage above indicates, his project is truly meant to serve capitalism. Again and again, Lanier takes pains to explain that his plan is not anticapitalist but a kind of reformist capitalism. Indeed, he frequently descends into classic “both sides do it” self-defensive posturing, so fearful of appearing insufficiently faithful to good old American capitalism. “Let’s reject the Marxist ideal,” writes Lanier, “and instead consider the question of whether markets can be counted on to create middle classes as a matter of course.” Lanier’s apparent answer to this question is no, given the book he’s writing, and yet his solution is to expand market relations to people and activities that are, if not free, also not matters of pure capital exchange.

This tic would be annoying enough in any book, but in one proposing vast changes to the capitalist economy that would entail enormous effort, it’s strange to be regularly confronted with fastidious resistance to radical ideas. “If you select the right passages,” writes Lanier after a paragraph of careful repudiation, “Marx can read as being incredibly current.” Do tell.

And that’s the real problem. I love grand ideas and the pondering of novel solutions to intractable problems. But the incongruity between Lanier’s sweeping proposals and his reflexive assertion that he’s not looking to upset capitalism’s apple cart bothers me. Lanier’s book is instructive for demonstrating how someone can recognize the great need for genuine change in a decrepit system and at the same time close their mind to direct and uncomplicated reform. My reaction to his dream is not to say, “That sounds impossible.” It’s to say, “Why not just take money from the people who are getting it and give it to the people who need it?”

Who Owns the Future? can best fulfill its mission by providing readers with a vocabulary of societal change. Given how powerfully Americans have been conditioned to fear the mere mention of socialism, we might have to settle, in the short term, for big thinkers that stay comfortably in the capitalist box, while we in lower orbits ponder the boundaries of the possible. For all its fussiness, confusion, and dead ends, the book offers a sobering consideration of the kind of structural economic problems that Americans are habituated to see as beneath them. In arguing for restoring the value produced by the people to the people, he may be playing in the capitalist sandbox, but the castle he is building is redistributive and bent on economic justice. I’ve read worse.

Of course, Lanier’s plan won’t be put into place, and the masters of our universe will continue to believe that, somehow, the economy will correct itself — with innovation, or disruption, or dynamism, or some other soggy term that explains nothing and conceals everything. Meanwhile, more people will have their stable jobs disrupted from under their chairs, just a bad day at the markets away. What should disturb us most is not merely that the last financial crisis caused companies to shed so many workers but that so many seemed to do it with no real impediment to their daily operations. How many of the young white-collar middle-class workers stuffed into offices spend half their time on Facebook and YouTube? In a proceduralist country obsessed with efficiency, who is efficient enough to feel safe at work? And how long before that feeling of precarity compels them to tear the whole edifice down?