Unless you’ve avoided all sports news since Thanksgiving, you’ve probably heard the name Tim Tebow, the Denver Broncos quarterback and evangelical Christian who likes to thank his lord and savior Jesus Christ for winning football games. Despite his awkward throwing motion and his dismal stats, Tebow still led his team to six “miraculous” comebacks, including completing an unlikely 80-yard pass in the first seconds of overtime to beat the favored Pittsburgh Steelers in a playoff game last week. Already controversial from his college days — his painting John 3:16 in his eyeblack prompted the NCAA to ban the practice — and from a Focus on the Family-sponsored anti-abortion ad that ran during the 2010 Super Bowl, Tebow’s eagerness to talk about his faith as much as win games has made him a touchstone for a debate about the role of religion in sports. “Tebowing” has even become a verb, describing the act of dropping to one knee and touching one’s forehead in apparent praise of God as Tebow frequently does.

Though the scale of hype may make Tebow seem at best a flash in the pan and at worst a prop in a cynical NFL marketing scheme (Charles Barkley has called him “the national nightmare”), the Tebow phenomenon is nonetheless a uniquely American one, tapping into the long intertwining of sports and religion in the U.S. It dates back to the Puritans, who considered sports sinful idleness that detracted from godly work. But as historian Robert Higgs points out in God in the Stadium: Sports and Religion in America, a competing Christian ideal rose up in America to counter the Puritans: the Christian knight, the progenitor of muscular Christianity, whose icons include Theodore Roosevelt, Andrew Carnegie (who popularized the Gospel of Wealth), Amos Alonzo Stagg (pioneer of American football and Yale divinity student), and James Naismith (Presbyterian minister and founder of basketball, a sport explicitly designed for missionary work).

In the First Great Awakening in the 1730s and 1740s, huge Protestant revivals swept across the colonies, shaping the American evangelicalism to come. Revival preachers like John Wesley and George Whitefield emphasized theatrics and entertainment, which yielded accounts of falling, “holy jerks,” dancing, sweating and other “exercises” at meetings. “The campground revival was our first tailgate party,” Higgs writes. Physical activity became associated with movement of the Holy Spirit, “emphasizing the heart as opposed to the head, the spirit and power in the blood.” Presbyterians, Methodists, and Baptists — Tebow’s denomination — took up the call. Throughout the 19th century, during the Second Great Awakening, American politics, religion, and sport all shared an outward momentum: to push the Western frontier, to spread the Word and win souls, to exercise and be outdoors and recruit a team of others to do the same.

By the mid-19th century, the Christian knight of muscular Christianity was primed for battle. The idea that exercise was conducive to a healthy mind and soul was thriving at Harvard and West Point. And the squalor and unhealthiness of emerging cities and the specter of disease helped overcome the Puritanical aversion to athletics, historian William Baker points out. “The muscular Christian movement” — championed by such men as Thomas Wentworth Higginson, who argued for it in a series of essays The Atlantic Monthly from 1858 to 1862 — “began not as a passion for competitive games but rather as a concern for healthy diet, fresh air, and firm muscles,” Baker writes in Playing With God: Religion and Modern Sport. “Health crusaders considered the body a sacred temple of God…. To grow up ‘puny, frail, sickly, mis-shapen, homely’ was to sin against ‘the Giver of the body.’ ” The Civil War became a testing ground for these ideals, and even in the wake of its devastation, surrogate battlefields quickly took shape in the decades that followed, as baseball, football, and basketball were well on their way to collegiate and professional organization.

Later in the century, YMCAs would become hugely influential in winning young men to Christianity through “the baptism of the gymnasium” and a focus on the trinity of baseball, football, and basketball. And as pro sports took off in the early 20th century, the evangelical link to athletics brought forward a sort of popularity gospel in which success on the field could be understood as illustrative of the rewards of faith. Consider Billy Sunday, one of the most famous evangelicals of the 20th century, who began as a professional baseball player and later made evangelism itself a kind of sport, with a scoreboard tracking registered conversions.

Traditionally and theologically attuned to the power of any kind of stage, evangelicals have had a special relationship with sports. Evangelicalism and professional sports make for a natural marriage, and evangelicals have in recent decades recognized the vast recruiting potential in the sports market. As religion scholar Charles Prebish notes, “If lucrative television contracts were making club owners and athletes into fiscal wizards, while providing ample exposure to an adoring public, then perhaps it was time for professional religion to imitate professional sport.” Football reaches far more Americans — and of many more stripes — on a regular basis than traditional politics or pulpits. “Look at the attention focused on the Mormon Church since Brigham Young University became a national football power,” Jerry Falwell commented when the fundamentalist Christian university he founded entered NCAA Division I football.

Given all this history, to be an evangelical in America means to accept, on some level, a muscular and imperialistic interpretation of Christianity. And conversely, to be a high-profile American athlete, regardless of personal religious affiliation, is to absorb on some level a theological motivation for winning. “Just as religion has been warped to justify sports,” Higgs writes, “so sports have been warped to assist in preparation for war and the waging of it, as a technique in the training of soldiers but mainly as a reinforcing symbol of manliness and knighthood.” When Tim Tebow drops a knee and thanks Jesus for his success, he is not just an athlete; he is a Christian athlete and exemplar. As Higgs notes, “It is sometimes difficult to distinguish between a Christian athlete and a muscular minister.”

From one perspective, Tebow is just using his celebrity status to simply do what evangelical Protestants have always been committed to doing: spreading the Word. But Tebow is also joining the ranks of those athletes whose religious identities have come to inform their personal brand and their fan base. When athletes instinctively use their public exposure as a platform for preaching (and ad campaigns), fans subtly shift to becoming congregants in the secular American church of what sportswriter Frank Deford dubbed “sportianity.” As former editor of The Christian Century Cornish Rogers asserted in 1972, sports were rapidly becoming “the dominant ritualistic expression of the reification of established religion in the United States.” Sports have become the central way we enact and celebrate what it means to be American.

What makes sports so compelling are the features they share with religious expression. In “Through the Eyes of Mircea Eliade: United States Football as a Religious ‘Rite De Passage,’ ” Bonnie Miller-McLemore boils down why sports are so critical to the American psyche: “Carefully camouflaged beneath the more obvious aspects of spectacle and sport, [football] embodies the ongoing power and survival of myth and ritual in popular culture. The game initiates a passage into a re-created state that reverses the oppressions of profane existence and brings about a moment in the presence of the sacred.” Profane time keeps marching forward; it doesn’t stop. Watching football interrupts the profane flow of time with sacred time, a dramatic spectacle that must be played out within an hour, albeit one meted out in carefully controlled and commercially interrupted dollops.

Whether in the stadium or in the living room, fans interact with sports in a way unlike other sources of entertainment. “Play and sport by their very nature alter reality,” Miller-McLemore writes. “Particular rules, regulations, limits, and goals create a sense of cosmos within a cosmos…. When we reduce the game by calling it mere entertainment, we overlook the extent to which the viewer as well as the participant becomes involved.” The fans are what enable the game to transcend a mere sequence of rules and exercises. Fans put on costumes, follow specific game rituals, speak to complete strangers, and get into fights, all for something that would “have little meaning or existence beyond that shared by this wide collective of observer-participants and the meanings that they construct and believe in together.”

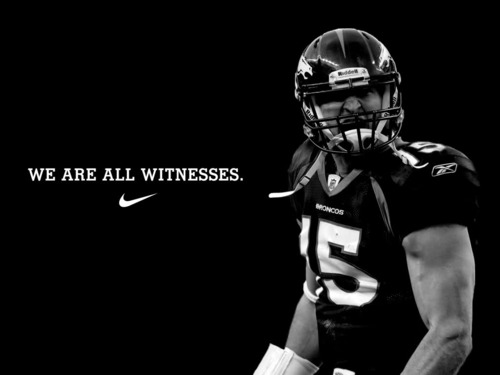

In other words, fans are witnessing. Like Christian conversion testimonies that become meaningful only when witnessed by members of the religious community, the Tim Tebow phenomenon operates the same way, and in no small part as a function of the way sports evolved with evangelicalism in this country. Look no further than fan-generated mash-ups of Nike’s “Witness” campaign with Tebow’s image. His improbable on-field success becomes important because we saw it, we were there, and we are talking about it. Tebow’s late season breakthrough isn’t so much a testament to Jesus being a Broncos fan as it is a testament to how large a community of secular witnesses football can generate in America. Regardless of the results of tomorrow’s game, Tebow is neither the alpha nor the omega. The tradition of which he is a part won’t end anytime soon. Another athlete will rise to remind us that our bleachers are also pews in the church-stadium built by previous generations. And let us say, game on.