The ISISCat is an LOLCat gone feral

“The trouble with a kitten is that eventually it becomes a cat.”

--Ogden Nash

ON the 25th anniversary of his invention, Tim Berners-Lee said his biggest surprise was to find the World Wide Web filled with so many kittens. The web is the world’s largest cat rendering plant: feline images are made, molded, and memed (or copycatted) to suit our representational needs. The cat’s uncanny flexibility as a sign has made it a powerful medium--and an unlikely weapon.

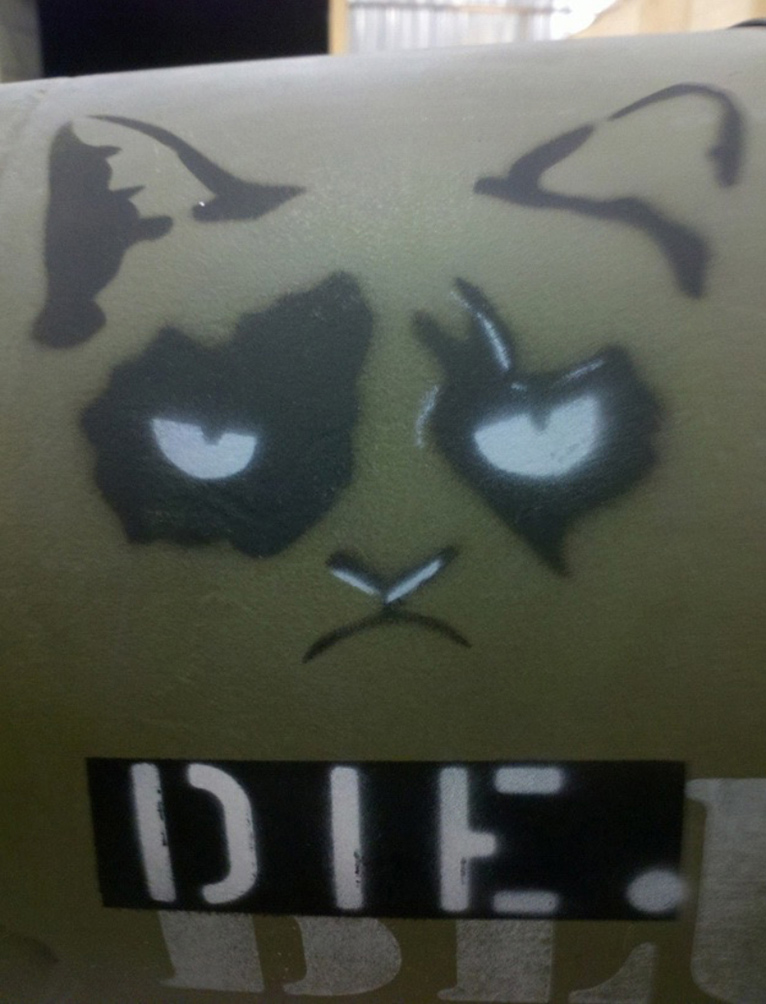

In March 2013, Reddit-user “nymattyd” posted a photo snapped by a friend serving in the U.S. Air Force depicting a bomb stenciled with the iconic feline and Internet celebrity Grumpy Cat. Immediately below Grumpy Cat’s scowling puss was a single message: “DIE.” Grumpy Cat had been enlisted in the War on Terror.

The Grumpy Cat bomb met its match just a year later with the introduction of a new species: the ISISCat. This feral offspring of the beloved LOLCat surfaced in the summer of 2014, first on Twitter and Instagram under the hashtag #catsofjihad. By mid-June, the species appeared on Twitter under the name Islamic State of Cat (@isilcats); it was a mysterious account that has since been suspended and whose slogan, delivered in cutesy LOLCat vernacular, read: “I Can Haz Islamic State Plz :).” Islamic State of Cat’s avatar--a plump cat sprawled out on a bedspread, the parts of an assault rifle arranged around its furry body--is accompanied by a crude rendering of ISIS’ iconic black flag. Just as in the Grumpy Cat Bomb, the message is clear: this cat is a weapon. It has been weaponized in the ISIS image war (volleys of visual propaganda spread through social media) against “the West.” ISIS’ English language propaganda often assumes a phantasmatic and monolithic West as its target. According to its online magazine Dabiq, ISIS seeks to “bring division to the world and destroy the grey zone” between this West and itself, echoing George W. Bush’s binary framing of the War on Terror: “you’re either with us or you’re with the terrorists.”

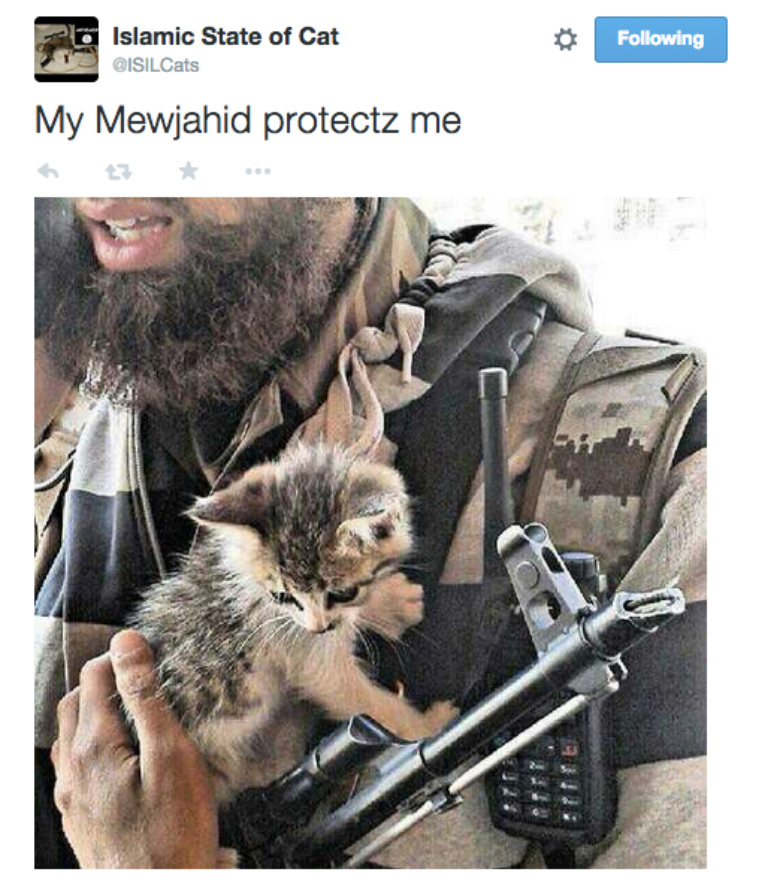

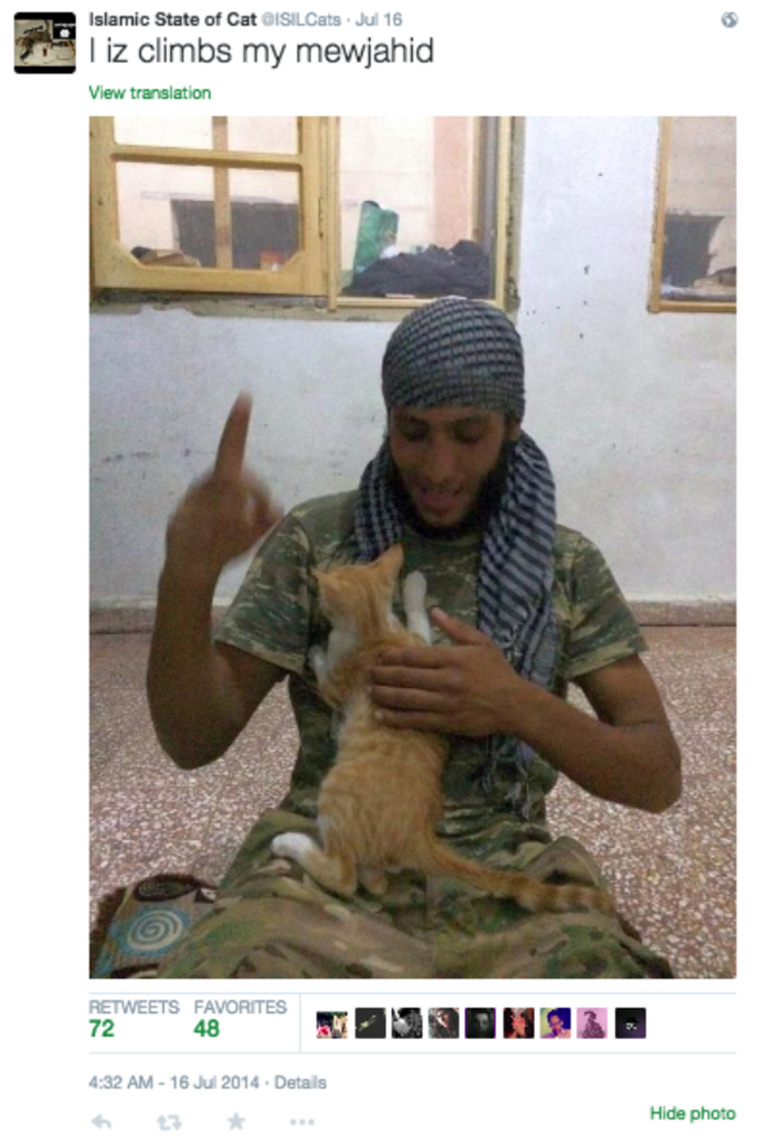

In the year that followed its debut, the account shared pro-ISIS propaganda interspersed with dozens of images of cats, often posing with ISIS militants. These tweets were written in humorous LOLspeak and identified their subjects, with a bit of clever wordplay, as “mewjahids.” As such, they combined two of today’s most popular genres: the LOLCat and the selfie.

Western pundits and politicians have so far understood ISISCats as a form of propaganda designed to normalize and “soften” the foreboding image of the militant group, while using “fancy memes” to lure so-called “foreign fighters” into the battlefield. But few have stopped to ask why ISIS, with its fearsome and violent reputation, would deploy cuteness--and specifically cute cats--in conjunction with videos of beheadings and mass executions to fashion its self-representation.

But who are the proper subjects, the mewjahids, of these unusual portraits--the cats or their human companions? These photographs construct a hybrid image. The cats, most of them kittens, are endowed with human characteristics. They function, in other words, as tiny avatars for the young men who have “gone feral,” leaving home for the wildness of war. A tweet posted on July 2, 2014, for example, depicts hungry kittens swearing allegiance to ISIS in exchange for food; another, from June 25, 2014, ascribes them faith by asking “Did you know: cats can drink from the water for ablution […]?”

In most of the portraits, the militant’s face is concealed by a mask, a sartorial choice that ensures anonymity but also outsources the affective labor to the cat, who gives the man a face with which to confront the spectator. By transferring the anthropomorphic qualities associated with cats back to the masked militant, the animal paradoxically humanizes the man. This also allows the human subject to resist objectification and return the gaze of surveillance. Unlike the famously aloof cat they have adopted as their avatar, ISIS militants are, as evidenced by the use of the hashtags like #AllEyesOnISIS and #NSAisComing, keenly aware of being watched by the U.S. national security state, which along with Twitter itself, monitors the site for extremist activity. These feline self-portraits harness such attention in a process that seeks to reverse the dehumanizing rhetoric of the War on Terror. Just two weeks after the 9/11 attacks, Bush vowed to find the perpetrators and “smoke them out of their caves.” This is the kind of framing that compelled American military personnel at the Abu Ghraib prison to stage photographs of prisoners as animals, most notoriously an image of military policeman Lynndie England leading a naked Iraqi prisoner by a leash.

There’s sadism in the process by which we render an animal cute, and a latent potential for cruelty and violence within the cute animal itself, qualities that are constitutive of its cuteness. As theorist Sianne Ngai argues in Our Aesthetic Categories, cuteness is “an aesthetic response to the diminutive, the weak, and the subordinate [that] depends entirely on the subject’s affective response to an imbalance of power between herself and the object.” Essayist Daniel Harris has similarly noted that an object “becomes cute not because of a quality it has, but because of a quality it lacks, a certain neediness and inability to stand alone…” Also tellingly, Ngai argues that we perceive cuteness in things that “seem sleepy, infirm or disabled.”

Ethologist Konrad Lorenz was the first to argue that “cute response” had its origins in biology. His concept of the “Kindchenschema” or “baby schema,” proposed that certain facial and bodily characteristics in human infants--a large head, low-lying eyes, clumsy movements--trigger a caretaking response in their adult counterparts, which helps to ensure survival. This response, Lorenz argued, also fuels our anthropomorphic imagination, triggering powerful affective responses to baby animals with analogous traits.

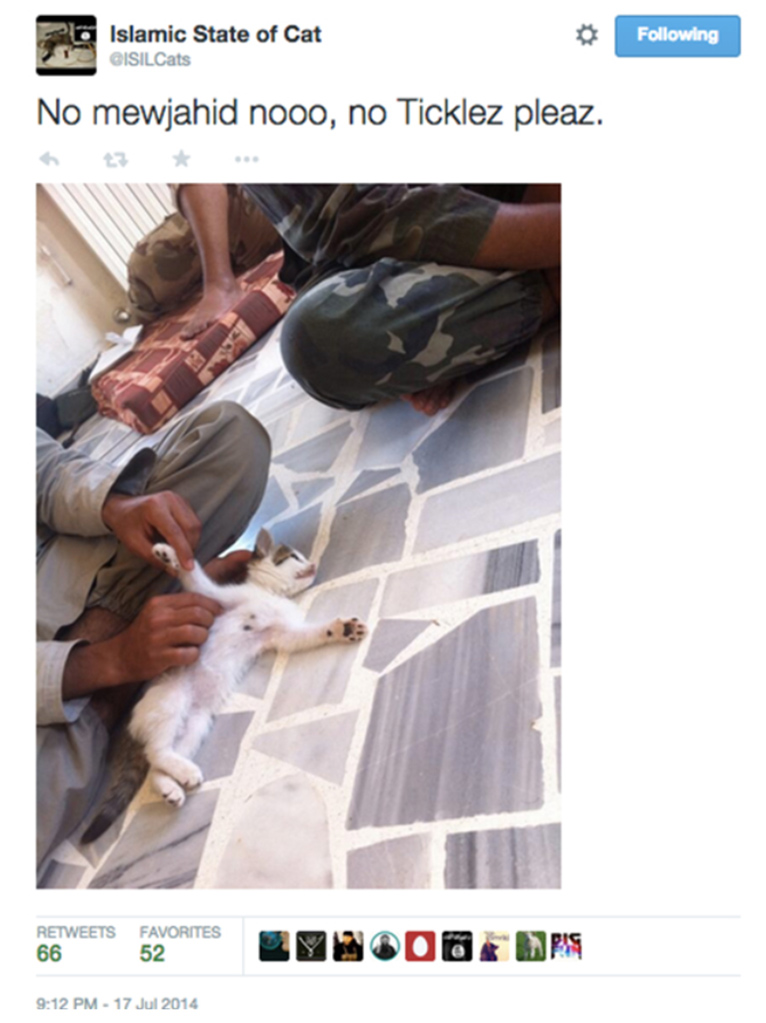

Cuteness does not simply trigger tender, caretaking feelings but also paradoxical impulses of domination and aggression. In a tweet posted on July 17, 2014, a militant tickles a small kitten. Whether the man is actually tickling the cat or simply posing for a shot, the act of tickling is suggestive in its ambiguity: tickling can take the form of pleasurable, intimate play and also of unpleasant and cruel torture. The humorous caption gestures toward this uncertainty as the cat cries “No mewjahid nooo, no Ticklez pleaz.”

Cuteness disarms us; it catches us off guard. The pet cat, a pinnacle of cuteness, is a plaything, or, to use geographer Yi-Fu Tuan’s formulation, a product of “dominance and affection.” The affective exchange in this play is ambiguous, but the cat’s status as a thing is not. The cat is an exemplary plaything because it is uniquely situated at the intersection of cuteness and cruelty. It is, as the Twitter account Refurb the Cat memorably suggested, “a sentient pillow filled with knives.” Furthermore, Ngai observes how encounters with cute things tend to deform or disrupt adult speech, triggering baby talk or the involuntary “awww.” ISISCats also provoke this mimetic response by deploying LOLCat baby talk to make viewers stop and fawn over its mewjahids.

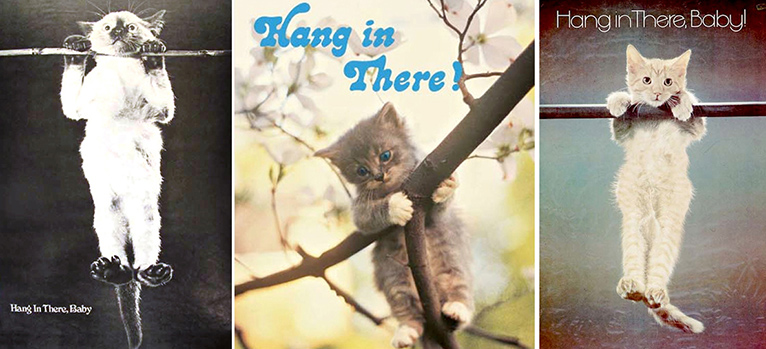

While cats enjoy an unequivocally cute status in much of today’s Internet culture, they have historically been represented with far more ambivalence. This duality is implicit in some of the most iconic representations of cats. A wildly popular motivational poster from 1969, for example, depicts a distressed cat dangling from a bamboo limb, captioned with the slogan “Hang In There, Baby.” Perhaps aware of the implicit sadism in the photograph, the designers of subsequent versions domesticated the image to a cuter and smaller one. The Onion supplied its own punch line to this proto-cat meme in 1999 with a satirical article headlined “Inspirational Poster Kitten Falls To Death After 17 Years.”

In a tweet posted on June 24, 2014, a man is shown playing with a kitten while crouched on the ground surrounded by trees. In his right hand, he holds a Steyr AUG assault rifle--butt on the ground, business end pointed toward the sky. The gun’s magazine lies flat, two grenades placed on its surface. The man holds his left hand above his knee, just out of reach of the kitten’s paw. The kitten stands on its hind legs, tail erect, gaze fixed on its target, while its left paw extends in an effort to touch the man’s hand. The caption reads “I can haz Steyr Aug? – Mujahid.” This is a scene of play between human and animal, but it also bears overt signifiers of violence: we see a militant taking a break from field duty and reloading his assault rifle while the cat, revealing his predatory nature, expresses a desire to possess the gun.

If we read the cat in this and other images as a figure that has been weaponized against the West, then this is a scene of an ISIS militant displaying his firepower--intended for the physical war as well as the cultural image war.

If we instead choose to read this as an image of a man and his cat, the mixture of intimate play with symbols of violence recalls the pet, which is always produced by affection and dominance. Here, the man teases the cat, using his raised hand to make the cat rise on its hind legs. The uncanny image of a cat standing on two legs is a staple of cute Internet cat imagery, perhaps because it pokes fun at the limits of anthropomorphism and underscores the hierarchy between the human and the cat. It is an image that diminishes the cat and renders him even cuter.

And yet, if we read the cat as a feline avatar for the ISIS militant, then its outstretched paw can be seen as a sign of swearing allegiance, while its stated wish to possess the gun underscores the militant’s desire to seize power through violence and topple his “Western” foe. Holding his palm over the cat, the man appears to draw from its power. The cat magnifies the man’s image as a canny predator, a creature of the wild. If the ISISCat is a self-portrait, then we need to consider the duality of the cat: its capacity for cruelty and the cuteness we project onto it. Resilient, resourceful and adaptable, the cat has nine lives.

W.J.T. Mitchell argues that the War on Terror “is really a war of and on a body of images, one which (as always) finds a way to mutilate and destroy actual, living human bodies, while the images themselves just grow stronger.” Through ISISCats, ISIS and its supporters seek to deploy the affective power of cute cats with the virality of memes to spread a new species of image.

Some suggest that ISISCats were devised by “foreign fighters”--young Western conscripts who grew up online, making LOLCats and snapping selfies. If this is true, then the ISISCat is an LOLCat gone feral. The uncanny power of these images radiates from the gap between the familiar and the foreign, the domestic and the wild. These images are weapons--they disarm not by dividing the “Western” spectator from the ISIS militant, but by playing in “the grey zone,” staging an intimate, yet conflicted relationship between them.