From New York to Switzerland, there are no films without banks

I hadn’t been in Zurich for even an hour before we declared cinema dead. The red eye from New York will play tricks on you, especially when you abandon the notion of sleep and spend the seven hours reading nearly an entire memoir by a prominent indie film producer who has recently quit the craft, sort of, because there isn’t a living in it anymore. Ted Hope’s Hope for Film wasn’t weighing on my yawning companions, foreign journalists who had come all the way from Los Angeles. We drowsily rode the Zurich Film Festival shuttle from the airport to our hotel, which wasn’t accepting us when we got there; it was 9 a.m. Central European Time but our rooms wouldn’t be ready until 2 p.m. The horror.

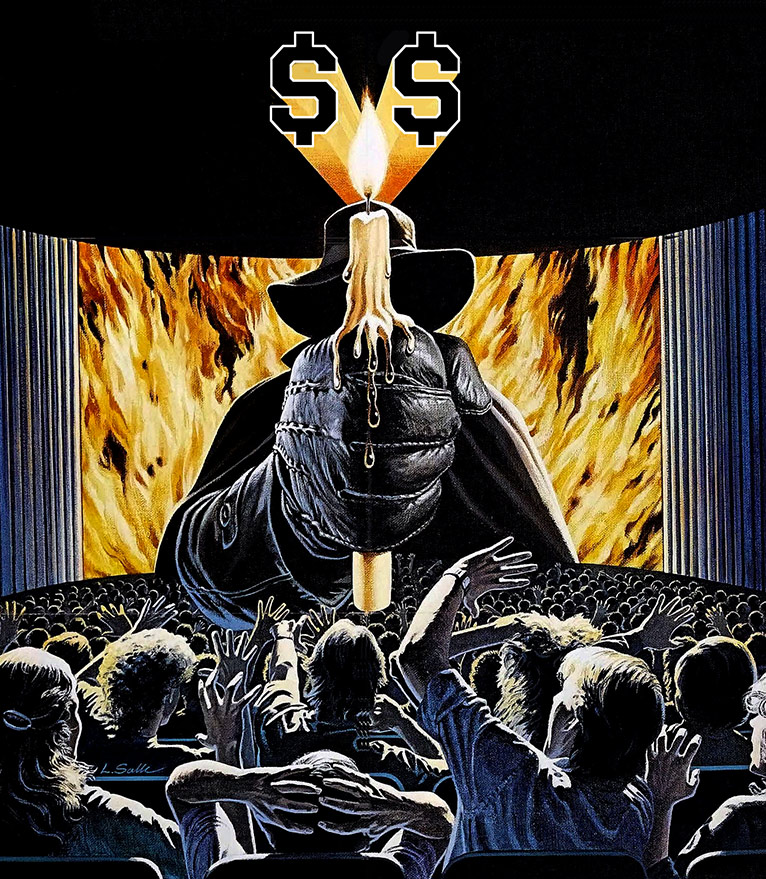

Perhaps nobody, out in the real world, really cares about “cinema” anymore we lamented as we sat on the couches in the lobby and talked about those many movies which seemed like they should be finding audiences but were not. Someone remarked on the silliness of any job that would pay us as little as it does to travel as far as we do to write about vain wealthy people’s efforts to crack the cultural conversation. Another thought the movies, at least in big cities, were too expensive, and a price-point shift would fix everything. Others thought it was the brutal efficiency, the all-consuming power of the Hollywood global marketing apparatus. One especially cynical person thought that in the future, small if not microbudget movies will have to transform into branded content, tied to the desires of corporations, in order to exist. Even if indieWIRE itself agreed with him, I held out hope he was wrong; the night before had left me thinking he wasn’t.

I spent my last evening in the US at a screening of Spent: Looking for Change, a doc featurette narrated by Tyler Perry that has been available on YouTube since June and has over a million views. It focuses on the financial struggles of four families of various racial and geographical profiles, who are the daily victims of unnecessary fees and predatory financial practices that thrive outside of the traditional banking and credit systems. The screening and the reception that followed were presented by American Express, which also paid for the film.

The world’s 22nd most valuable brand trotted out one of their executives -- in nice leather shoes and unassuming but surely very expensive jeans -- to host a panel afterward about the ways money is extracted from those 80 million Americans who don’t use banks, and what we can do about it. Then we walked a hundred feet to drink champagne and eat lamb sliders. I doubt much of the conversations centered on poor people or on the $75.7 million dollars our hosting moneylender spent ending an investigation into its misrepresentation of various credit products to 335,000 customers.

The documentary itself is competently and conscientiously made, though it’s generally unadventurous. Especially high on its list of unnecessary evils, all explained in Perry’s velvety and concerned cadence, are payday lenders and other check-cashing debt traps. These charlatans are pretty up-front about how they’re ripping off working Americans who are “unbanked”; they usually tell you if they are taking some ungodly amount from this check or the next one. That hasn’t stopped American Express, who obfuscates how they plan to fuck you, from being unduly concerned. A more fully rounded critique would have included how being “banked,” or having American Express cards, can also ruin you. Maybe it’ll be in the feature version, but I’m not holding my breath.

I went home with mixed emotions. I was pretty broke and needed those lamb sliders. I was sitting on three defaulted credit cards from when I made the decision to make my own movie, one that I was living with the consequences of every day. Spent has its heart in the right place, it’s just that the people that financed it don’t. One could say the same thing about most film festivals; the first “main partner” listed in the Zurich Film Festival catalogue is Credit Suisse.

***

The festival opened with the regrettable James Brown biopic Get On Up, but having already considered its lazy knownothingness elsewhere, the first screening I saw in Zurich was of the Mexican picture Gueros, the first feature from Alonzo Ruiz Palacios. It was scarcely attended. Held on a Friday afternoon, the first full day of the festival, this movie had premiered in Berlin. Zurich wants to be the first place a significant movie plays in the “German speaking realm”; its audiences seem to expect as much. Occasionally programming director Viviana Vizzani wants a movie so badly she’ll overlook the informal restriction, and this was certainly one of those instances.

The movie, shot in glorious black and white and edited with dexterity and grace, follows a pair of brothers in Mexico City over the course of a few days. Its title, like everything else about the movie, is droll but not to be taken literally. The younger one, who appears to be Caucasian (Gueros is Mexican slang for “white person”), has been sent by their mother, tired of his youthful hijinks that include dropping giant water balloons on unsuspecting newborns and their mothers, to live with his older sibling. A college student who is at the center of a student strike over the possibility of tuition being charged, the older brother doesn’t “look” white. He has little to say about the nature of student protests or the liberation of young people from needless student debt; the student strike is the background as the pair of brothers, along with a few interlopers, try to track down an infamous Mexican rock star now apparently dying of cancer. The whole thing is sweet if not savory, pretty if not accomplished, fun if not fulfilling. It is as uninterested in the Mexican caste system as is in the sustainability of radical politics, but calling Gueros an exercise in bourgeois aesthetics might be an overreach.

This was the tenth year of Zurich’s festival. It’s young and wealthy, a cultural boon in an old European finance capital where a cheeseburger at McDonald’s can cost $10. They can afford to foot the bill, often in tandem with the concurrently running San Sebestien Film Festival, and to fly in Antonio Banderas and Benecio Del Toro, Diane Keaton and Cate Blanchett. Placed after the fancy fall triumvirate of Venice/Telluride/Toronto, the program is full of films that previously premiered at those longer running and more prestigious festivals, as well as the bigger spring and winter events. The festival caused its biggest stirs in year four, when Roman Polanski was arrested shortly after landing here to receive a lifetime achievement award.

Zurich wants to be taken seriously as an industry event and regardless of how much money they throw at the problem, how many wonderful films they screen, that really isn’t up to them as much as an international consortium of dealmakers, none of whom make their decisions about a festival’s merits in concert, but through a process of taste-osmosis. One day, we all looked up and SXSW was considered a significant film festival. Hype had trumped reason and suddenly sales agents and distributors and journalists from fancy, endowed magazines started showing up to buy and publicize young white women who’d gone to Saint Ann’s with Puff Daddy’s children. It didn’t matter that the program stunk as much in 2007 as it would in 2014. It was part of the show now.

I already had the chance to dig into some of the festival’s bigger ticket items earlier on. Gone Girl, David Fincher’s adaptation of Gillian Flynn’s blockbuster novel, opened the New York Film Festival a day after Zurich began, three days before it would screen for the Swiss, a week before it opened throughout the world. I’d seen it nearly a month earlier in order to interview Fincher in time for a magazine deadline. Over chocolates or bratwursts, various Swiss people, and other non-Swiss people I only ever see in Switzerland (or places like it), kept asking me what I thought of it. Spoilers be damned, I normally obliged them.

Part procedural, part dirge-like diary of false exposition, part satire that turns ever more vicious even as some maudlin humanism bubbles up at the edges, this is a picture about a disappearance, an investigation into said circumstance and underneath all that, a failed marriage. Gone Girl tells its story using dueling unreliable narrators and a byzantine structure. Rosamund Pike’s Amy Dunne gets to narrate her fake diary entries, dramatized as expository interludes in the film’s first half, while Ben Affleck’s Nick Dunne gets to tell us one story as the protagonist in the film’s narrative proper and another altogether in front of the TV cameras and in private with the various women of his life. This allows the filmmakers to effectively shift the emphasis of blame from one end of the marriage in question to the other. Some find it infuriating that by picture’s end only the woman seems like a sociopath, but I suspect they are missing the forest for the trees. As timely and thematically expansive as any of Mr. Fincher’s work to date, Gone Girl indulges in both misogyny and misandry with a sort of “shame on both your houses” glee. It sits in the tradition of late ‘80s “Michael Douglas gets picked on by one crazy lady” pictures like Fatal Attraction, The War of the Roses, and Basic Instinct as it slowly peels the onion back on a marriage that contains two failed writers, one womanizer, one recession, and one trust fund.

Flynn’s middle America doesn’t seem to interest Fincher and cinematographer Jordan Cronenweth as much as I’d like it to. Only one location pops off the screen, when the local policewoman (lovingly played by the criminally underutilized Kim Dickens) stops by the local shopping mall in the mid-sized Missouri suburb where most of the film takes place. The literary couple at its center met and fell in love in New York, and it all came apart when they moved to the Midwest to care for sick parents and downsize their dreams. In Fincher and Cronenweth’s vision the mall has become a post-apocalyptic shelter for meth addicts, a roiling cathedral of filth. In Flynn’s story this is the type of place a woman who relies on the wealth of her actually successful writer parents comes to buy a gun, but it can also be seen as a symptom of the halcyon days of economic collapse.

The shopping mall as site zombified consumer culture has been a trope in popular cinema as long as we’ve had George Romero, but here it gets retrofited for the meth age. Fincher doesn’t seem to much care; he’s admitted to rooting for his anti-heroine in the movie in several interviews, and when she says in one of her voiceovers that her adopted hometown of North Carthage, Missouri is “the navel of the country,” we’re led to believe this isn’t unfounded snobbery, but an observation of genuine insight. On the edges of his cynical adaptation of Gillian Flynn’s novel, class resentment simmers, both within a marriage that was undertaken under the illusion that the world would open itself up with opportunities, and out in the mall of North Carthage.

***

When I returned to New York, the 52nd New York Film Festival was in full swing. It doesn’t need to buy its reputation, even if most of the journalists standing in the rain to catch the first glimpse of Paul Thomas Anderson’s gonzo Pynchon adaptation Inherent Vice or Laura Poitras’s incendiary Ed Snowden verite doc Citizen Four have no idea who Amos Vogel was. The NYFF feels more central to New York film culture than ever. A few years back the Film Society decided to get younger and you look up one day, two years into the Kent Jones-Lesli Klainberg era, and you realize it has succeeded. Most of the staffers I know are central-Brooklyn gentrifiers.

As always, the NYFF gets a smattering of the most talked about movies, the best movies, the movies that leave you enraged. The old narrative and documentary auteurs -- the newest entry in “Late Godard” is here (in 3D!), as is the end of “Late Resnais” (he’s dead!) There’s more “Late Wisemen” and “Late Maysles” (those guys seem like they might never die or are already dead) alongside the mid career greats: the aforementioned Fincher and Anderson along with Olivier Assayas, Alejandro Gonzales Iñárritu, the Dardennes, David Cronenberg, and Hong Sang-soo, to name a few. There are also a few celebrated neophytes like Alex Ross Perry, Damien Chazelle, and The Safdie Brothers.

Birdman, by the once promising, frequently maligned, and now returned to critical favor Iñárritu, closed the festival. Emmanuel Lubezki, the 50 year old Mexican cinematographer who is widely considered one of the premiere DPs in the world, has outdone himself in Iñárritu's newest film. Forget the Michael Keaton “returns with a character that mirrors his own career arc” line everyone in the mainstream media is pushing about the film, forget that it represents the fullest payoff on the talent Iñárritu displayed in his Amores Perros 14 years ago -- “Chivo,” as his collaborators call him, is the real star of the show, the master behind the film’s formal ingenuity.

The shooting in Birdman -- an otherwise pedestrian, if well-acted, backstage dramedy about a fallen movie star who once headlined a superhero franchise and now hopes to gain some measure of critical respect by adapting and starring in a version of Raymond Carver’s What We Talk About When We Talk About Love for the stage -- achieves a technical virtuosity that transcends the material. It is in every way a triumph, one that surpasses Lubezki’s work on otherworldly films like Terrence Malick’s The Tree of Life and Alfonso Cuarón's Gravity. Shot entirely in and around the St. James Theatre in two weeks, the movie is a visual high-wire act, combining shots seamlessly to create the effect that the movie (which includes its fair share of CGI special effects, extras and ballet-like blocking arrangements) is unfolding in one long take. Iñárritu has cited such Russian slow cinema stalwarts as Alexander Sokurov and Andrei Tarkovsky as influences, but neither of those guys ever had Chivo. In its own very self-conscious way, the film finds a middle ground between the truly non-commercial cinema that takes form seriously and finds spectacle and fantasy childish, and the Hollywood tent-pole work that so many of its characters loath and/or need.

It’s an actor’s movie in some ways -- Edward Norton, as a self-serious Manhattan stage method actor, has never been used to greater effect -- it being mostly comprised of intimately observed, emotionally complicated moments. But unlike most movies that fit that description, the artifice and plasticity of the medium is always smack dab in your face in Birdman. The beautiful trick Iñárritu and his collaborators have pulled is that, by the final glimpse of Emma Stone’s face, full of wonder as she stares out a hospital window at an act of metaphysical joy, you’ve stopped asking “How?” and started whispering “Wow.” Perhaps combining the spectacle of trash and slow cinema’s earnest consideration of time is the only future the movies have left. You wouldn’t know it from the trailer from Birdman though; Fox Searchlight is selling the thing like another superhero movie.