Bananas, artichokes, and salsify, reviewed.

Edited by Atossa Abrahamian

Anti-Banana

by ELISA GABBERT

The "unique” taste, texture, and “design” of bananas leave much to be desired. To speak first to the taste: Bananas are one of the few fruits that is not even appealing to children when converted into candy form—banana-flavored Runts and Laffy Taffy are among the most swapped, nay, reviled kinds of Halloween candy, left along with Tootsie Rolls and Bottle Caps at the bottom of the plastic pumpkin. Cherry-flavored and appleflavored candies, on the other hand, may taste nothing like their namesake fruits but are at least appealing qua junk food.

Banana flavor out-bananas bananas and, as such, reminds us of health food when we’re trying to focus on sugar. The texture of bananas rivals microwave oatmeal and lowfat yogurt in sheer lack of appeal, requiring no involvement of the teeth whatsoever.

The design flaws of the banana are legion. Unless housed in a hard, banana-shaped casing (an object which is available for purchase but has no other conceivable use), bananas decompose in the process of being transported. When more or less than perfectly ripe, the stem resists snapping, causing the top inch of the banana—the all-important first bite—to be smooshed into a paste. Must I go on?

Yes, bananas turn black when placed in the freezer. Let us remember that uniqueness is not in itself a virtue. This “unique” feature of bananas primarily serves to remind us that we are essentially eating garbage. Compared to apples, which can last in the fridge for weeks, the pre-garbage window for bananas is remarkably short, a few days at best, and this is true only if your embarrassing father or an aging aunt perversely prefers rotting bananas. Watching (not to mention smelling) a person eat a banana in a blackened state, one feels Death’s icy fingers graze the back of one’s neck.

Bananas may have some interesting structural facets. For example a Trivial Pursuit card once informed me that bananas have five “sides” (yes, they are in some sense pentagons or perhaps even pentagrams). However, the topic of structural concerns brings us to one of the most disturbing facts about bananas, a fact that is rarely spoken of. This fact is banana strings.

Bananas have strings. Strange strings that connect the peel to the fruit and seem to belong to neither. Are you supposed to eat these strings? Are they digestible? No one is saying.

And yes: the noun banana is initially pleasing on a superficial level. But notice how it skirts the palindrome question. It is almost a palindrome, but not quite. Much like the fruit is, on occasion, when perfectly yellow with no brown spots but no fibrous green ends, almost a tasty snack—but not quite.

Pro-Banana

by CATHERINE MENG

Bananas have endeared themselves to us in such creative ways that it is hard to imagine a world worth living in without them. Humor, music, poetry, recycling, and failed recreational drug use all owe quite a good deal to the banana.

Linguistically, bananas share many of the same characteristics as Mississippi, in that children and Gwen Stefani like to shout out their spellings. Would Bananarama would be where they are today if their name had been Grapeorama? And would the world be guffawing its head off at Buster Keaton had he slipped on a grapefruit?

If you stick your finger in the middle of a peeled banana cut cross-wise, it will evenly split into three sections like the Mercedes Benz logo. And if you put it in the freezer, it will turn black.

Without bananas we would not have the funny story about that time at summer camp when we tried to smoke banana peels nor the Dead Milkmen song that gave us the idea. Did you know that during the 19th century, as a preventive measure to cut down on the risk of slipping on a banana peel, cities relied on wild pigs to dispose of rotting organic matter? This later led to the first recycling programs in the United States. Just think, without the banana there would be no recycling. Only landfills and wild pigs roaming the streets ...

Sure, bananas aren’t cute like berries, practical like apples and oranges, or great baked in pies like peaches or cherries, and they get all mushy in fruit salad—but when we stop comparing the banana to other fruit and appreciate it for its own unique taste, texture, and design, we should acknowledge that the banana demands perhaps not our fan-club membership but at least our profound respect.

Perhaps bananas were set up for failure when they were labeled as fruits. Some day, an elite research team in Holland will publish their groundbreaking paper that scientifically proves there is a new phylum or kingdom or whatever, and that it comprises bananas, platypus, and Gwar. Bananas!

Desperately Seeking Salsify

by KARA BLOOMGARDEN-SMOKE

It's a good idea to be able to correctly pronounce the name of the obscure vegetable you are trying to find.

I met my friend at the Farmer’s Market in McCarren Park in Williamsburg, Brooklyn. We went early, so it was all babies in pea coats and dads with facial hair. After an egg sandwich from the egg-sandwich cart, I set to work.

I had once seen “smashed potatoes with salsify” listed on the blackboard of a Brooklyn-themed restaurant in Williamsburg and was never sure whether it was a real thing. So I decided to find out.

“Do you have salsify?” I asked at the stand with the better produce and long lines. I cut the line, past the people clutching dandelion greens and rainbow chard. I pronounced it like salsa-fi. The farmers, who seemed like they knew what they were talking about, had never heard of it. My friend told me it was pronounced sal-sif-i. I asked at another booth, pronouncing it her way. “You mean salsa-fi?” the farmer said. He didn’t have any either.

While searching for salsify, I ran into Jordan, this guy I know who owns a farm-totable— or, rather, farmers’-market-to-table type place in my neighborhood. He seems quite fond of sorrel. I figured if anyone could tell me about salsify, Jordan was the guy. But Jordan didn’t know. He didn’t really know how it was pronounced or where to find it. Although he gave me the names of some Union Square Farmers who may know. But I never did make it across the river.

I pulled out my iPhone and Googled “salsify season” and “salsify recipes.” Some things I learned about salsify: It’s a member of the sunflower family. It’s a root vegetable. You can eat both the root and the leaves, although the root isn’t too pretty. But that’s okay. If you are the kind of person who is cooking salsify, you should not be the kind of person who is overly concerned with appearances. It is planted in the spring and harvested in the fall, after the first frost. So theoretically, now is the perfect time to give it a go. But try telling that to the good farmers of the McCarren Park Farmers Market. It takes 150 days to grow.

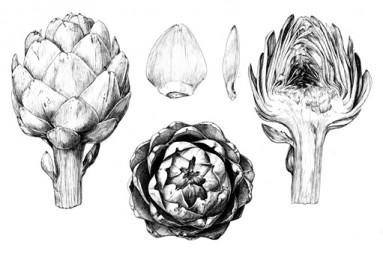

“The most surprising thing about salsify, the first time you eat it, is its flavor,” the Washington Post wrote last January. “Traditionally it is called ‘oyster plant,’ a name as inaccurate as it is unappetizing. The roots taste nothing like oysters, and nothing like parsnips either. They taste like artichoke hearts.”

It sounds delicious. I like artichokes a lot. I like oysters; even if salsify doesn’t taste like an oyster I wouldn’t mind being the judge of that. Too bad I still haven’t found it. I’ve since looked in Chinatown and other farmers’ markets, but to no avail.

Maybe when I grow up, move to Park Slope, and start picking up my weekly CSA box, I’ll finally satisfy my salsify curiosity. Or I’ll go to a Brooklyn-themed restaurant in another state and look up at the blackboard and there, nestled between the Amish Chicken and Kale Caesar salads, I’ll once again see the elusive root vegetable. This time, I’ll order it. Someday, somewhere, I will go to a restaurant or a farmers’ market or a dinner party and eat something that tastes like an artichoke but isn’t.

And then I will know that my quest is complete. I will have experienced salsify.

How to Eat an Artichoke

by LILLY O’DONNELL

Artichokes are usually sold in jars, little X-Files alien fetuses floating in oil. But to buy them that way—jarred or canned, 11 already tamed—is to miss out on a carnivorous experience. It’s like buying a slab of venison wrapped in cellophane vs. taking down a deer in the woods.

Eating an artichoke is about the thrill of the hunt. Artichokes make you work for your supper, not like spinach or sweet peas or baby carrots, which you can just shove into your mouth raw without a second thought. The artichoke is tough. Its spikes, nestled at the tips of its tightly huddled leaves, would prefer for you to back off. And even after you cook them for 45 minutes (steamed is best), the work isn’t over. You have to skin it, discarding the first couple of layers of protective leaves. Then, you tear the softer leaves off like fingernails, scraping the meat with your teeth.

Artichokes do not bleed, but if you dip the leaves in melted butter and let it run down your chin, biting into one is no less primal than eating a juicy, bloody steak.

Of course, the leaves are but details— amuse-bouches for the real deal. Once you’ve devoured them, the remains strewn about, covered in teeth marks and droplets of coagulating butter, you reach the delicious innards: the artichoke’s heart. In a feeble, cowering attempt at self-preservation, the artichoke heart is covered with tiny, hair-like spikes that will make you cough and sputter if they get caught in your throat.

But this defense mechanism is no match for spoons. Scrape off the fuzz, rinse the heart out, hold it up to the sky, and gorge yourself.