In a narco-hypnotic trance, at four a.m., I dial a man’s phone number. He lives in New York and I live in Los Angeles. I am awake in the bedroom I grew up in, where for years every inch of white space was papered over with magazine cut-outs of rockers and actors. I’m in the most perilous phase of the pharmaceutical stupor. The narcotic-grade sleeping pill my body is burning through numbs my frontal cortex, the part of your brain that tells you to stop. An impaired cortex is no excuse for making the initial phone call, but it does help explain the subsequent redials I make after first hitting voicemail. It also accounts for some magical thinking. I am calling the man I love. He hasn’t spoken to me for three years, but this is not the first time I have called him in the middle of the night, hoping to catch him groggy in an East Coast dawn. We were together for one compressed, tumultuous year, a period when we were both making rude attempts at adulthood. I set the distance between us. Our relationship collapsed, and I was the one who walked. It was not my first major relationship and I have dated since; I even told another man I loved him. But every couple of months, for the past three years, I have called the man in New York to ask for him back. This night, my desire feels so giant, so true, that I am convinced it exists beyond me. Some cosmic tug must be occurring. He must feel it too, I think. I dial again.

On the fourth try his voice, still scratchy with sleep, breaks through.

“ ... Hello?”

“Hi,” I say in the most neutral tone I can muster. “It’s Natasha.”

“Are you joking?” He is agitated but not angry, as if inconvenienced by something trifling.

“That would be a bad joke.”

The line goes dead.

After some sobbing and a second sleeping pill, I knock out just before daylight. In the morning, my moral inventory produces the usual mixture of horror, embarrassment, and self-pity. I resolve never to pull this sort of stunt again, never to allow myself to slip so far downward and inward that I start looking up early morning flights to New York.

Time has indeed healed the psychic wounds of most past relationships—even the ones that involved a shared lease—but in the case of the man in New York, time only mystified what had happened between us. In truth, part of what enabled my histrionic behavior was the sense of ethereality I experienced while dialing. It was somehow momentarily affirming to let my pride dissolve, to give in to something grander. I knew that, for a time, when with the man in New York—we’ll call him M.—I was at my happiest. After our relationship I had done the work to make myself whole, and now, as a total person, I still wanted him. It was not out of some co-dependent need, I believed. When I thought about our time together, I did not crave our complementary weaknesses, I clung to the complementary differences I had taken for granted. There was, of course, something terrifying in my attempt to engage a personality that I had blown up to mythic proportions, but it was also invigorating, even sublime, like staring into the expanse of the ocean or being up so high you see the curvature of the earth. J.H. Van de Berg describes this sensation as the libido’s lurch towards the exterior world:

The libido leaves the inner self when the inner self has become too full. In order to prevent it from being torn, the I has to aim itself on objects outside the self. Ultimately man must begin to love in order not to get ill ... Objects are of importance only in an extreme urgency. Human beings, too.

My deification of M. felt equal parts bracing and humbling. Weren’t these feelings a sign of something beautiful, some yielding to form? Wasn’t Romanticism based on this sensation? Wasn’t there in fact a noble tradition of surrendering to the terror, the swoon?

Writing this now, I think of Cher’s open palm thwacking Nicolas Cage’s slack-jawed face in Moonstruck, the best romantic comedy in film history. Cher’s character cheats on her fiancé with his dopey-eyed brother (the one with the wooden hand and the lacerated heart). Furious that she’s let herself sleep with him, she leaps out of bed the next morning and shouts, “Y'know, you got them bad eyes, like a gypsy!” He tells her that he’s in love with her and can’t let her go. A hard thwack! He says nothing; she slaps him again, even harder.

“Snap out of it!” goes Cher.

Camille Paglia is my Cher. She’s a hard-boiled Italian; she counters my gooey solipsism with hard blows. Before her, nothing could shift my perception of romance: not the span of a continent, not periods of promiscuity, not vigilant celibacy, not pleas from friends, not the sound reasoning of a deft psychiatrist. For me, Paglia’s greatest merit as a critic is the fact that her literary analysis can double as self-help. So many feminist readings of art tend to be heavy-handed and personally worthless—X marginalizes women because Y, endless nattering about the male gaze, leaden treatises about being left out and so on. This agitprop is largely useless if you have to figure out, say, how to feel about an unrequited text after an evening of casual sex with a doctoral student. What Paglia’s writing demonstrates is that critical interpretations by women that concern themselves with women's experience (as opposed to a political agenda) can make great art meaningful—even helpful—for women as women. The near absence of women's voices in the history of art is a loss largely because we don't have their accumulated wisdom to help guide us today.

Reading Paglia on the poetry of William Blake was one of the few intellectual experiences that changed my emotional life. For Paglia, Blake is the British Marquis de Sade, probing and exposing the tyrannical impulses behind misty emotionalism. Blake is interested in “coercion, repetition-compulsion, spiritual rape.” Like Rousseau, Blake wanted to free sex from religious and social restraints, but unlike Rousseau, Blake recognized there is no escaping the domination of nature and our own ignoble desires. His poems are filled with a latent human amoralism: men and women cannibalizing each other (“The Mental Traveler”), physically and psychologically exploited children (“The Chimney Sweeper,” “The Little Black Boy”), erotic ambivalence (“The Sick Rose”), and resentment towards the demonic power of sex.

It’s Paglia’s insight into an often-ignored Blake poem, “Infant Joy,” that exposed me to my own coercive caress.

I have but no name

I am but two days old. —

What shall I call thee?

I happy am

Joy is my name—

Sweet joy befall thee!Pretty joy!

Sweet joy but two days old.

Sweet joy I call thee:

Thou dost smile.

I sing the while.

Sweet joy befall thee.

The poem has a “devouring presence,” Paglia says. “This is one of the uncanniest poems in literature. Seemingly so slight and transparent, it harbors something sinister and maniacal. The infant is given a name by a greater power. The infant has no voice. It is silent, passive and defenseless against the person who cradles it.” The poem’s dialogue eerily mimicked for me what it felt like to be on the other end of M.’s dial tone. His silence, I suddenly understood, was in part a reaction to my insistence on immediate intimacy, my hope to bypass any sort of reacclimation and plunge right back into high romance. I wanted his heart so furiously I would tear through bone to get it, though I knew I had to approach softly.

In one liberating spank, Paglia’s reading of the poem made me realize that my phone calls and romantic gestures were not noble or life-affirming but a perverse, coercive form of power. What I perceived to be my romantic idealism was actually a fascistic impulse to dominate, what Paglia describes as “sadistic tenderness”: “Every gesture of love is an assertion of power. There is no selflessness or self-sacrifice, only refinements in domination ... Romantic love—all love—is sex and power. In nearness we enter each other’s animal aura. There is magic there, both black and white.”

When I say that we didn’t speak for three years, I’m not being entirely honest. One time we got back in touch and engaged in some friendly, light emailing, and after one brief but affectionate phone call he suggested we visit. In Las Vegas. We share a birthday, and “we could celebrate it together,” he said kindly. I was delighted, but then, in a sudden moment of clarity, I asked if he knew what he was getting into. I could tolerate being ignored, I said, but ambivalence would crush me. It was “all or nothing.” When I told him that it would break my heart if we slept together, he disappeared back into the East Coast ether, rescinding the offer and cutting off contact. For months I regretted revealing myself so thoroughly. I strategized. I would get back in touch, but this time—gently. I would creep silently, hovering, as though to a crib. Once reengaged, I would be a simple, soothing presence. I would demand nothing. I would secretly wait to devour.

Part of the reason I felt compelled to call M. in the middle of the night was to recreate the physical charge he must have felt waking up next to me. “We have regressed to the infancy consciousness,” Paglia says. “Sensory experience is the avenue of sadomasochism, ‘Infant Joy’ recreates the dumb muscle memory of our physicality.” I hoped to trigger whatever remnants of me still existed in his blood, to recreate the warmth of my body pressed to his in the sensuousness of my voice. Or perhaps it was closer to a blind grope. As Eric Fromm says, “For the authoritarian character there exist, so to speak, two sexes: the powerful ones and the powerless ones.” What is more powerless, I secretly reasoned, than a state of unconsciousness?

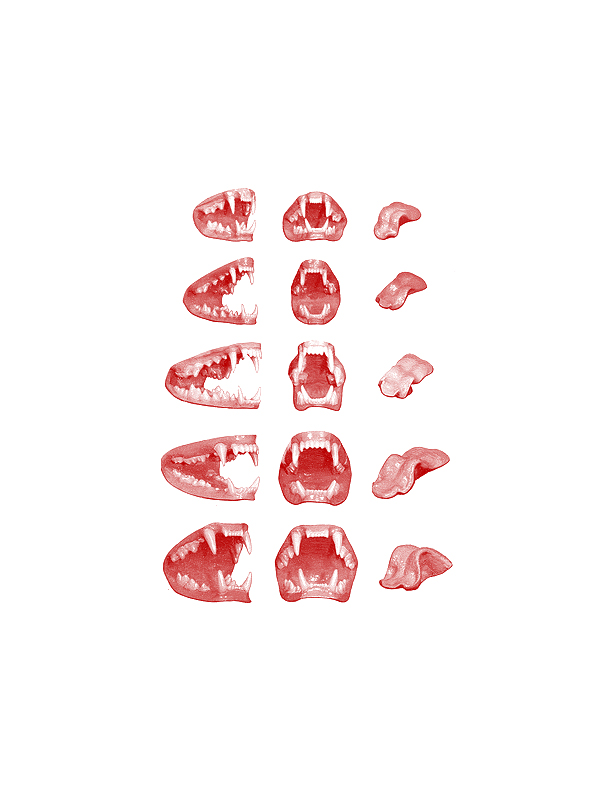

I call my impulses toward M. more fascistic than romantic because of the naked attempts at coercion, the tyrannical power dynamics between a rapacious figure (me) and a passive one (him). This vampirism disguised as romantic love is for Paglia a constant theme in Blake’s poetry. In Blake’s sexual grand drama, there is typically a character—sometimes the reader—who seems possessed with a bloodthirst, “a demonic black energy.” What I had originally identified as fullness, a libido-bursting abundance of emotion, the sort that Van de Berg describes, was actually a withering emptiness. What I craved, with a compulsion akin to thirst, was not only M.’s affection, but for his actual life to belong to me again.

It shouldn’t come as much of a surprise when I tell you that most of these panicked phone calls came during downswings in my emotional life, when I felt most dejected, unsteady, and lonely. I would coax M. back to me with breadcrumbs of sweetness and nostalgia but meant ultimately to tie him to me again through flesh (i.e. fucking). The vampire gains her victim’s life-force through ceremonial seduction. “Sex is how mother nature kills us, that is, how she enslaves the imagination,” Paglia says. At the core of the dynamic is death: the vampire, already a corpse, makes a cadaver of the victim. Love is a necromance, a death cult.

The vampirism and death in the (non)relationship is also reminiscent of themes found in fascist art. “The fascist dramaturgy centers on the orgiastic transactions between mighty forces and their puppets,” Susan Sontag wrote in 1980. “Its choreography alternates between ceaseless motion and a congealed, static, ‘virile’ posing. Fascist art glorifies surrender, it exalts mindlessness, it glamorizes death.”

Fascism infantilizes its victims. One of the best cinematic depictions of this principle is Palo Passolini’s Salo (1975), the cinematic adaptation of Sade’s 120 Days of Sodom. Fascist oligarchs kidnap countryside school boys and girls, and subject them to a litany of sexual cruelty, humiliation and torture (the opposite of Moonstruck). The movie is vile and riveting. It provides a scathing condemnation of fascism by depicting a universe where rapacious excesses go unchecked. Unlike the sexual delirium depicted in pornography, where body parts fill up the screen, all of the sex scenes in Salo are filmed coolly, in cavernous halls, and from far away. The long-shot camerawork miniaturizes the participants, obscuring their movements, reducing them to fuzzy white globs, geometrically posed. Viewers feel they are watching from balcony seats. This gives the sex crimes an even more voyeuristic, transgressive flavor. We instinctively lean forward in our seats. This sensation is what Paglia describes as the “rapacious eye.” The distance between M. and me allowed my compulsion to intensify, ultimately obliterating his form. The details of the relationship faded as M. became a more distant, diaphanous, and tantalizing figure. The infant is blind, “but we aggressively see,” Paglia says, and “along the track our seeing skids our unbreakable will.” In this void, my loquacious gaze thrived. I re-measured the trials of the relationship, newly desirous of that which was out of my reach.

None of these insights made me stop calling M. He finally called back, and we talked for hours. We were kind and amorous. Paglia gives no insight into what happens next. Our birthdays are coming up again. Viva la muerte.