Drinking on the old, mossy fortress in Viejo San Juan, talking about bitcoins, exes, and the eyebrows of María Félix, it’s hard to imagine we were ever not friends. We met on the internet in 2016, when we discovered each other to be the only people writing in English about the dead Puerto Rican poet Marigloria Palma. From the page she beckoned us to listen and to write back in poems, which we called translations. We both raged over why she’s so rarely read, and rage can be intimate when it’s so specific. The first time we met IRL, we spent the whole time yelling. Even our laughter screamed.

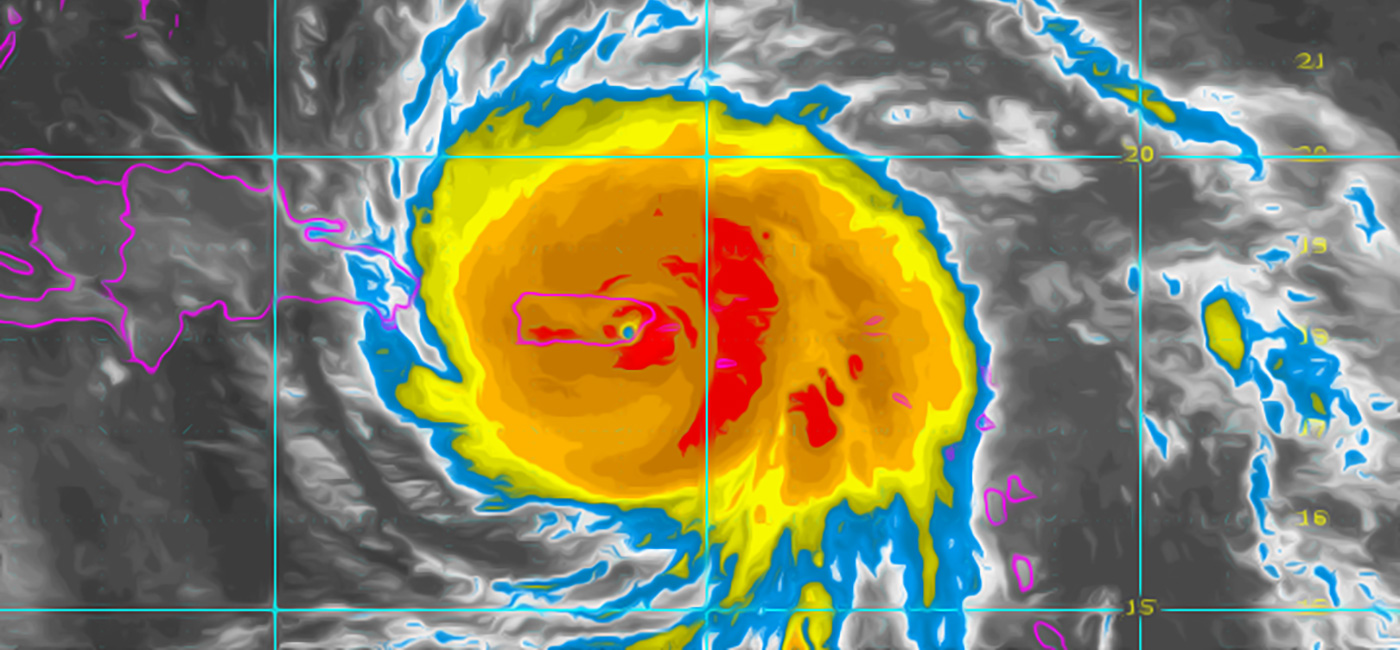

Neither of us expected the devastation brought on by Hurricane María. We formed a nuclear group with poets and translators Ricardo Maldonado and Erica Mena, and the four of us compiled work by poets on the island and in diaspora, printing a series of handmade bilingual broadsides called Puerto Rico en mi corazón after the slogan used by the Young Lords. These poems helped us raise over $3,000 for the grassroots organization Taller Salud, which supports public health and gender justice on the island. But our group was more than editorial: We formed a family, far-flung and necessary, a net where we could catch each other while the grief flowed through us.

We’ve both been on the road with our writing, our relationship to Puerto Rico on the page both shored up and devastated by the disaster capitalism that comes for the culture industry as much as any other sector of the economy. Our correspondence has been a way to tether ourselves to the real work of tending to each other. We’re often each other’s first readers, with the translator’s infinite patience for a single turn of phrase. We both know that a politics of care is fundamental to translation: Just one word can tear down a kingdom or cradle una flor de marta. These are letters from fall 2018, sent en route from city to city. From our point of view, in this exchange, every city is Puerto Rican.

Raquel Salas Rivera

& Carina del Valle Schorske

•

AmigXxXxX,

I found you when I was actively searching for poetic predecessors on the island, out from my mother’s profound disillusionment with the misogyny of the Nuyorican poetry scene in which she participated in the ’70s. I had just begun translating Marigloria Palma’s work from the same period as a kind of evasion or alternate route, depending on the day. Google took me to you through her: I found you reading her poems about New York on YouTube—“Nueva York con paloma.” Spanish doesn’t lie about the fact that “doves” and “pigeons” are the same birds, so the shared word is able to embrace both romance and contamination, an urban intimacy.

I also found an essay you’d written for VIDA on Julia de Burgos that quoted one my favorite stanzas of Palma’s. You translated:

My sadness, that wet piece of cardboard that moans

against the wall;

that fusion of rain and dead tree,

that dog, lost in a forest of smoke,

that dirtied scrap of yellow news.

I translated it differently, in the first line, as “that wet brown box / moaning against the wall.” I think I was unconsciously influenced by Zora Neale Hurston’s description of her raced body-and-soul as “a brown bag of miscellany propped against a wall.” The resonance between these lines made me see the color of the cardboard. But we’d come to the same stanza to say something, and your anger electrified me: “Marigloria Palma, la jevota, la megamujerota. You don’t even know who the fuck she is.” I did know, but barely. I was at the beginning. You said “she will translate an old anger, one that precedes your encounter.” I felt directly addressed, “called out” if calling out meant something different than it does now. You were coming from a deeper saturation in the literary culture of Puerto Rico, but I saw that you too were grappling with the lineages we inherit, make, and break. Sometimes I find essays about Julia de Burgos frustrating bc it’s like . . . obsessively circling a single grave in the middle of Potter’s Field when there’s a whole cemetery singing and seething around her. She was and is a part of that polyphonic song. It’s like José María Lima says—our friend Mara Pastor quotes him in her new book—“hay una canción / pero está rota / y es inútil decirla en pedacitos.”

Back to the question of lineage—I guess I’m wondering about any early experiences you had of choosing poetic or political kin. So much is unchosen, and I’m interested in that too, what we’ve received or can’t help carrying on. But right now I’m wondering about the choosing and the needs that drive it. The way I chose Palma . . .

Choosing you,

C

•

Amigaaaa(ay),

Acabo de volver de Puerto Rico. I just came back from the Festival de la Palabra, where there were so many beautiful things. In particular, I remember speaking to a group of high-school students who have formed a literary club in Río Grande, and one of them described receiving the criticism that her use of ay was outdated. The force and anger with which she defended it, and her refusal to change that ay in her work, made me think about those moments when language points to its own excess. Like ay coño, or maybe ay ya, which mirrors itself, or maybe meets in the middle y like wings of a bird, ay being excess and ya being the cutting short of excess, but in the paradox always sort of exceeding itself.

Of course, Marigloria loved ay. It was a sincere love, a sincere belief that something was happening, an evocation, an invocation, an outer-inner. You and I do that when we talk, right? I mean we sort of pull at the ay, try and find words for what it does, add to its excess. This is why we share a love for the essay, that genre that in the Caribbean seems to do so much more than critique and something other than poetry.

As for doves and pigeons (Hello, pigeon!), aka palomas, really really, en veldá en veldá, one of my first memories as a child was being in el parque de las palomas feeding the pigeons. I have a picture of one on my shoulder eating from my hand. I’m sure it wasn’t hygienic, but my mother couldn’t find it in herself to deprive me of the love I had for this common city bird. What is the distinction between dove and pigeon if not a distinction between ciudad y campo, city and country. You know me enough by now to know this makes me think of history, of migrations within a country (Puerto Rico) that lead to migrations without a country (New York). These narratives we inherit, a la Carreta, in which we have fallen from grace, migrated to the big then bigger city in which we are ground to nothing by the machine. ¡Ay, if only it were true! But instead we survive and become something other than what we were before, an amalgam of losses and inventions, immigrants, or residents of movement. You know, allá afuera.

Con toda la fuerza del amor,

Raquel

•

Fuerza de Amor,

There you are, on the road! The excuse for my slowness is I’m on the road too, in spirit.

I just wanna hear you screaming ay bendito. It’s weird how that excess becomes a tag at the Latinx superstore. Say a certain kind of ay y ya todo el mundo sabe que eres boricua. (As if we ever let one minute go by without letting folks know. Pa que tú lo sepas.) I didn’t want to bring in “Despacito” pero aquí estamos. After the summer of “Despacito” was the autumn of the hurricane and a song that wearied me could make me cry at the bodega if I caught it at that contagious ay bendito moment. For me I just wanna hear you screaming / ay bendito became awkwardly linebroken to magnify the desire the empire has to hear us screaming, whether in pain or celebration—it doesn’t seem to matter much so long as it produces a lucrative spectacle. And yet you know how I love our lifesaving loudness. I just wanna becomes a kind of minimum desire for maximal expression. I know how to love a well-worn phrase, a played-out song. Sometimes I can bite it so it bursts and I can swim in the spit of everyone who’s said it. La muchedumbre.

When I was in Puerto Rico this August, I stayed at an Airbnb for a few days before staying at Nicole’s, because my cousin was having an emergency hysterectomy and couldn’t host me at the last minute. I met a tourist there—am I a tourist there?—who’d gone down to La Perla to follow in the footsteps of the “Despacito” video, and she scrolled through photographs of herself stretched out on the concrete rim of el Bowl, the concrete skate bowl that neighbors fill up with a hose on the weekends to make a seaside pool. The public artist who built el Bowl (Chemi Rosado-Seijo) calls it a “micro utopia” and I wonder how to use latinate techno language without sounding like a cryptobro. “Puertopia” is an ugly word, but ultimately so is “Puerto Rico.” Where are your micro utopias, beyond el parque de las palomas?

I feel you saying that “country” works in English like “paloma” works in Spanish—collapsing a difference that maybe shouldn’t be understood as difference. In English “country” is both “nation” and . . . not city. Where my mother bathed summers in a big tin tub under the mango tree, etc. How can we love that country fiercely without immediately making it a country, theirs or ours. Is there another kind of claim to make? El Bowl is so country—so country-cum-city. It’s not that I really want to set up a wall to keep that particular tourist away from it. I just want her to know it’s not her country.

X,

C

•

Carinística,

Pues mira, mija, Julio Ramos once made a point about the word pueblo (was it Julio or was it me?). He/I/We were like pueblo is people/town/country. Perhaps the body of a nation? Perhaps the idea that nation is a people? I’ve always hated this idea, for example, that American is an identifying marker beyond empire. As in, I am an American because my formation is in the United States. No, you are an American because you cannot disentangle identity from imperialism. There is this very important debate between James Baldwin and Audre Lorde published in Essence Magazine in 1984 (one year before I was born). It starts with Baldwin:

JB: [ . . . ] Du Bois believed in the American dream. So did Martin. So did Malcolm. So do I. So do you. That’s why we’re sitting here.

AL: I don’t, honey. I’m sorry, I just can’t let that go past. Deep, deep, deep down I know that dream was never mine. And I wept and I cried and I fought and I stormed, but I just knew it. I was Black. I was female. And I was out—out—by any construct wherever the power lay. So if I had to claw myself insane, if I lived I was going to have to do it alone. Nobody was dreaming about me. Nobody was even studying me except as something to wipe out.

I think this is a very important moment because it offers the possibility that to identify as American is not a given. So, I’d like to start here. No one is born allied to empire. No one has empire imprinted in their marrow. If to be un-American meant you lost your job, died, were blacklisted, and to be non-American means you are bombed, persecuted, and disappeared, then what is there in this word that so many people within the confines of this country are attached to, if not the promise that their lives can be better than the lives of the excluded.

Me fui por la tangente. Digo todo esto porque no soy gringa, sí, no soy gringa. No es tour para mí, ni es gozo, ni me gusta imaginar que puede haber una opción para Puerto Rico que no incluya una libertad futura, porque si Puerto Rico va a sobrevivir el cryptocapitalismo, tenemos que quitarnos de encima la sanguijuela del imperio.

Lo dejo ahí por ahora,

Raquel

•

Raqueloque,

Ah that interview is so fucking evergreen! I kinda wonder if Audre Lorde’s experience as a child of Caribbean immigrants shaped or sharpened that perspective, but it’s not the only way to get it. Like, Ntozake Shange was born and bred in Trenton to black bourgeois parents with a long history in this nation. When she passed on earlier this week, her lines came back to me: “i have always hated being referred to as an american citizen / though i love the western hemisphere.” She changed her own name. No soy gringa. There are a lot of ways manifest destiny can cross you, a lot of ways not to believe in America or its interpellation of you as American.

But whenever I begin to gesture around a feeling of complicity, as I did in describing the micro utopias that remain open to touristic penetration, maybe mine, you interrupt the gesture. I see you do this with other stateside Puerto Ricans who speak haltingly, in a broken way, of our relationship to a place our parents or grandparents were forced to leave as part of an explicit program of depopulation. It takes work to learn why we are where we are when the experience of choosing is so central to how we see ourselves. Even though our American citizenship as Puerto Ricans was imposed in 1917 without choice, I think it often seems easier to survive it if we interpret our journeys to new cities, the joy of new diasporic encounters, as chosen, of our own making. But if/when we get radicalized, this sense of choice shadows our relationship to Americanness. I think the question you’re raising is whether even a negative attachment to America, a sense of guilt or responsibility, is really just the imprint of imperial patriotism. Whatever it is that makes me stumble over the words No soy gringa—is that thing in my way when I imagine who or what world I am beholden to and fighting for?

I’m not sure. I know I don’t share Baldwin’s stated belief in the American Dream and that my vision of justice is not nationbound. But this is the week of Trump’s threats to birthright citizenship, an ambivalent element of the U.S. Constitution that has made various colonial exceptions in relation to Native Americans and Puerto Ricans, to say nothing of how threadbare and conditional it has been even for people it has claimed to protect. And yet we must fight for it. But maybe fighting for the rights of others to stay where they are does not require defending the hollow construct of citizenship or acting grateful for a style of citizenship that was never desired.

It is very good—endlessly enabling—that my Puerto Rican family has not had to live under the constant threat of deportation here in New York, as all other immigrants do. This is not the same as it being good that Puerto Ricans are American citizens. Especially since, on the island, Puerto Ricans have been subject to all kinds of informal and ongoing deportation to the United States. My abuela doesn’t talk much anymore, but she was lucid last week and I marveled to her over the fact that she’s lived in the same apartment in Washington Heights for 65 years. Is New York your favorite place? I asked, feeling touched by a ray of late light cutting through a red tree at the far end of the courtyard. She looked absolutely disgusted. No. No. So where then, I asked. Puerto Rico, she said, like I was dumb.

~ Carina

•

Carinística,

Pues, claaaro. Place and nation are not the same. Nation is just whatever the state says about itself through repetition and interpellation, right? And if that state is imperial, it says it about itself elsewhere, in blood, bullets, silencing.

This week I got into an argument with a stateside Puerto Rican who was defending Lin-Manuel Miranda. There was a moment in which I wrote, “Just as I believe in consent in interpersonal relationships, I believe in consent when it comes to political and economic power.” His response? “That’s irrelevant. The political status of the island is just an excuse by all sides for doing nothing.” This is what happens when a colonized subject identifies so much with the colonizer that they are willing to make excuses for his worst crimes. To believe that only gringos uphold empire is to forget that Puerto Ricans have been complicit in the exploitation of other Puerto Ricans since the invasion. Consent? That is irrelevant! So says a defender of a defender of the PROMESA bill.

During the discussion something very interesting happened. I never doubted Lin-Manuel’s puertorriqueñidad, yet the person I was arguing with responded defensively, insisting that Lin-Manuel was also Puerto Rican. When did identifying as Puerto Rican become more important than political and economic consent? Well, with the further development of cultural nationalism under Muñoz Marín and his argument that political independence was secondary to “cultural” independence, that one could have one without the other, that one could feel free without being free.

If being Puerto Rican means getting to wear a flag without caring that that flag was made alongside the Cuban flag by separatists, or that waving that flag was illegal for many years, I’m not sure I want part of that identity.

That being said, nos hace falta la solidaridad. Too many Puerto Ricans wear their U.S. citizenship like a badge of pride, something to differentiate them from other immigrants, but that is what we are, immigrants, that is what we deal with, and when the day comes that our citizenship is revoked like Paul Robeson’s passport was taken away after he testified before the HUAC, we better be ready to join forces with all the other immigrants to fight against the fascist state.

Abrazotes,

Raquel

•

Palomita,

As if “one could feel free without being free.” I’m hearing Kanye in that unholy decoupling of feeling and being. The Kanye of “Father Stretch My Hands Part 1,” where he repeats:

I just wanna feel liberated IIIII . . .

The I works like an ay there, that’s the tone. But what makes him feel liberated, is, like, fucking a model who’s “just bleached her asshole.” The feeling can’t last. Because actually feeling free is no more attainable than being free. Feeling is not “just.” It’s not easy or minimal or divisible.

I think of “Father Stretch My Hands” in counterpoint to Nina Simone’s version of “I Wish I Knew How It Would Feel to Be Free.” (The jazz musician Billy Taylor originally wrote it for his daughter.) Superficially the sentiment might seem similar, but grammar matters here, as ever. She is not willing to stop short at feeling free; she wants to know what it would feel like to actually be free, to “remove all the chains holding me” and “all the thoughts that keep us apart.” Somehow in articulating the truer and more difficult ambition for actual liberation, we’re closer to it. Her driving piano accelerates towards an event horizon where feeling meets being:

Then I’d sing cuz I know

Then I’d sing cuz I know

Then I’d sing cuz I know

How it feels to be free

I know how it feels

Yes I know how it feels

How it feels

To be free, no no

Or know know. There are a few ways to hear those last lines, her improvised outro. One way is that knowing how it feels to be not free is a form of knowing how it would feel to be free. That freedom begins with saying no to unfreedom. Too often, a liberal like Lin-Manuel is saying yes please but maybe to unfreedom and calling that liberation. I’m not feeling it and don’t wanna "just."

But back to Ricans we can roll with: One of my favorite Marigloria Palma poems is called “Twilight” (the title’s like that, in English), where she writes:

A trompetazos de alma

defiendo mi emoción

de la mordida gris

del desencanto.

Right now I have something like:

To the soul sound of trumpets

I defend my feeling

from the grey bite

of disenchantment.

Palma recognizes that her capacity to feel freely, with intensity, is a precious resource that must be actively defended—the metaphors get kinda military, with the trompetazos. Her feeling is not a resting place, really. It’s feeling for or towards a freer world, por y para.

Ay, ya. Lo dejo aquí por ahora. Just for now.

<3 Cari

•

Carina, amor y amiga,

Yes, and then this is a utopian spark or a capacity to feel future or a desire to say no. Of course to be against feeling free as I articulated it is to be against feeling free without freedom, which is not to feel (the) free, but to promise (dar tu PROMESA) to deliver feels one day that are like freedom. I think of Lin-Manuel’s song “Almost like Praying,” where all the pueblos of Puerto Rico are listed, and how different it sounds from Hurray For the Riff Raff’s “Pa’lante.”

Lin-Manuel’s song lists these towns, but not their people. The only mention of a politics is a brief moment in which “Grito de Lares” is name-dropped. The video shows not scenes from Puerto Rico but a studio full of famous artists. It is a strange kind of celebration, a sort of “Puerto Rico se levanta” slogan that fits neatly on Coca-Cola cans but doesn’t capture the rupture, pain, and loss of the hurricane.

Then there is “Pa’lante,” a music video that opens without music, but with the sounds of cars passing puestos de fruta, a horse eating in an empty lot, the wind moving through the palms, the water hitting the beach where a house has been destroyed by the hurricane, seagulls and chickens near La Perla. Then we see a woman with her child walking down the steps of La Perla towards the beach, walking past the debris and then looking down at her little girl before looking out toward the ocean. Then, and only then, does the music come in. This is what it means to listen before speaking, this is what it means to imagine a future, not for you and your rich friends in a studio, but un futuro puertorriqueño desde Puerto Rico y la diáspora. ¿Cómo echar pa’lante? Con amor, con respeto y con dignidad.

When I hear this song I feel sad, and I also feel, yes, what freedom could be.

When we write to each other I feel sad, and I also feel, yes, what freedom we could make, we could feel together. “I just wanna fall in love / Not fuck it up, and feel something.” And feel something. And feel something. And feel something.

Then there is the part that kills me, lives me, brings me back, que me morivive.

Well lately, it’s been mighty hard to see

Just searching for my lost humanity

I look for you, my friend

But do you look for me?

Is this not the call from the colony, an anti-love song against empire?

And so I want to hold onto this rage and sadness as a form of hope, as a pointing to a way out. I want us to promise to each other that we will keep fighting until it looks like what it should, until it feels like freedom because we are finally free.

Te amo, querida,

Raquel