The NFL has used empiricism’s tenets to mystify the link between concussions and head injury. But “science” can’t defeat “Mom logic”

I recognize the tinkling Chopin in the NFL film from third-grade ballet class. Football players clash onscreen. “On this down and dirty dance floor,” the male voice-over intones, “huge men perform a punishing pirouette. The meek will never inherit this turf. Because every play is hand-to-hand and body-to-body combat.” It’s like ballet, but violent, “down and dirty,” “combat.” In a perverse citation of the Sermon on the Mount, the voice-over casts out the meek, as if to fend off any hint of femininity. One of football’s most famously violent drills is called “The Nutcracker.” It’s not a reference to the Tchaikovsky ballet; it’s a reference to head injury.

The PBS Frontline documentary League of Denial, based on the book of the same title by Mark Fainaru-Wada and Steve Fainaru, offers this clip about 25 minutes in, as an example of the NFL’s official aestheticization of violence. It lets the -gendered premise lie there, plain to see yet unremarked. Gender everywhere structures the documentary’s account of NFL head injuries: who can claim knowledge, who can claim connoisseurship, who can claim love—and what kind. Female caregivers, especially mothers, are cast in a special relationship to “the truth” about head injury, one whose only authority is moral. Yet the film ostensibly concerns itself with gender only in passing, and typically distances any mention of it.

The documentary departs from this strategy only once, when the neuropathologist Ann McKee—apologizing, hesitating to name it even as she calls upon the authorization of her generational experience of years in a male-dominated profession—affirms that sexism played a role in the NFL’s reception of her research. “According to Dr. McKee,” says the voice-over, not openly endorsing McKee’s statement. But the excruciatingly long, stumbling response of Henry Feuer, the Indianapolis Colts team physician and member of the NFL’s mild traumatic brain injury (MBTI) committee, speaks volumes:

I, I, y’know, I don’t know why she feels that way. That she presented herself … as I recall; it’s been several years … that, that, something … something in her manner and, and … I think she’s a brilliant woman; she’s done a great job … there’s just something, just about the way she said it … and, and not that everybody was looking down, it’s just … um … [Voice-over: “Dr. Feuer insists Dr. McKee is mistaken about how she was treated.”] … if we, if we coming, came across as disrespectful, then everybody else that we interviewed for the, over the fifteen years must have felt the same way. Uhh, that’s all I can say about that. And I feel strongly about that, too. [Pause.] We would just, we would listen and thank you, and, and that’s it, whether she wanted us to start, yeah, I don’t know where she’s coming from on that.

Feuer lobs anything and everything at hand: He denies the reality of McKee’s experience while at the same time affirming that the committee was indeed patronizing and dismissive, but blaming it on McKee and “something … something in her manner.” And then, after claiming that the experience was specific to McKee and her fault, due to the way “that she presented herself,” Feuer adds that her experience could not have been sexist because it was the way that “everyone” was treated. It didn’t happen; it happened; it happened, but only because of something personal about Ann McKee; it happened, but it wasn’t sexist because it happened to everyone. Men of science.

League of Denial weaves together a tale of two publics whose memberships are contested and gendered masculine. First, do you get the game? Do you understand the power of combat, the beauty of the “punishing pirouette,” what the fresco in my undergraduate gym called “the glory of manly sports” and what the anthropologist Clifford Geertz called “deep play”? Are you a member of that public? “I get it,” Ann McKee, a lifelong football fan, explicitly affirms to the camera. But she is not allowed to “get it.”

And second, do you have scientific expertise? Are you rigorous? Do you have the facts, the hard facts, the hardest facts, to prove beyond the shadow of a doubt not only that being hit on the head causes long-term brain trauma but also that this trauma is a bad thing or that the hitting on the head is really caused by the kind of hitting on the head that happens on the field during football games, as opposed to other kinds of hitting on the head, or any number of factors that could cause early-onset dementia, the early-onset dementia that seems to strike so many former football players? In League of Denial, we are shown that the NFL’s strategy is to merge the publics of scientific consensus with that deep play. It’s a matter of who can be trusted, who gets to be an expert. It’s a matter of who’s in.

***

Geertz's 1972 essay “Deep Play: Notes on the Balinese Cockfight” drew aesthetics into the practice of ethnography in a new way. The Balinese cockfight, in all its violence and mass-cultural appeal, he argued, is an art form that tells us as much about Balinese culture as ethnographic chestnuts like kinship structures or gift giving. The cockfight “is, for the Balinese, a kind of sentimental education. What he learns there is what his culture’s ethos and his private sensibility … look like when spelled out externally in a collective text.” In The Sun Also Rises, Ernest Hemingway called the achievement of that sentimental education, with respect to the Spanish bullfight, afición. The “only a game” that is “more than a game” has the status of art—Geertz’s comparison is not the ballet but Shakespeare’s Macbeth—and performs the same function, but it is explicitly masculine. “To anyone who has been in Bali any length of time,” Geertz notes, “the deep psychological identification of Balinese men with their cocks is unmistakable. The double entendre here is deliberate. It works exactly the same way in Balinese as it does in English, even to producing the same tired jokes, strained puns, and uninventive obscenities.” Women and foreigners are functionally excluded from the Balinese cockfight. The parade of NFL officials, coaches, doctors, and spokespersons—all men (mostly white) but for one or two lawyers—show how they are functionally excluded from football’s deep play too.

Deep play is enacted on bodies, human or animal, that will be violently sacrificed for this art. Fainaru-Wada and Fainaru report, “New England Patriots coach Bill Belichick believed that the Nutcracker answered some of football’s most fundamental questions: ‘Who is a man? Who’s tough? Who’s going to hit somebody?’” To understand deep play is to be an aficionado of a masculine art of violence. “I mean it’s, it’s affected my life, but I’m not out there crying about it,” says former Oakland Raider Jim Otto early in the film. “I know I went to war, and I came out of the battle with what I got. And, uh, you know, that’s the way it is. That’s the way [former Pittsburgh Steeler] Mike Webster [the first posthumously diagnosed case of football-related chronic traumatic encephalopathy, or CTE] would say it too, I’m sure of it. We battled in there.” Battle is an art with deep significance, and either you understand or you don’t.

***

Ira Casson was promoted to co-chair the NFL’s MBTI committee in 2007, an at least nominally reformist move since he, unlike the previous chair, Elliot Pellman, was a neurologist. In a press conference that year in response to growing concerns about head trauma, Casson was unambiguous in rooting his authority in his identity as a certain kind of knower and a certain kind of believer: as scientific. “Anecdotes do not make scientifically valid evidence,” he stated, thus reducing evidence of CTE in former football players to the status of that story you tell about your cat. “I’m a man of science; I believe in empirically determined, scientifically valid data, and that is not scientifically valid data … In my opinion, the only scientifically valid evidence of chronic encephalopathy in athletes is in boxers and in some steeplechase jockeys.”

NFL experts—team doctors, MBTI committee members, even coaches and NFL commissioner Roger Goodell—all affirm a belief in scientific expertise characterized by a modesty or parsimony about its claims to knowledge. Historians of science Steven Shapin and Simon Schaffer, in their classic study of 17th century natural philosopher Robert Boyle, name this the position of the “modest witness.” The turn to experiment initiated by British empiricists like Boyle changed the standards of evidence. Deductive reasoning and logical consistency became less important than observed phenomena: If you saw it, it was true. The true was no longer a matter of the always true, as in deductive reasoning; it was a matter of punctual events, witnessed and recorded, preferably repeatedly, but not always. (Boyle’s air pump leaked.) This meant that the humans doing the witnessing had to be trustworthy, a determination made on thoroughly social grounds. “It is absolutely crucial to remember who it was that was portraying himself as a mere ‘under-builder,’?” Shapin and Schaffer observe. “Boyle was the son of the Earl of Cork, and everyone knew that very well. Thus, it was plausible that such modesty could have a noble aspect, and Boyle’s presentation of self as a moral model for experimental philosophers was powerful.” The NFL, in statements like Casson’s, deploys a historically evacuated and fully Reddit-ready philosophy of science made of slogans like “the plural of ‘anecdote’ is not ‘data’?” and “correlation does not equal causation.” On this basis, the NFL makes itself the seat of both aesthetic afición and scientific validity.

Recourse to such convenient maxims ignores the practical limitations of doing experimental work in medicine and public health, which, for ethical reasons, often precludes doing the outright controlled trials that could help establish causality. Moreover, the group in question, current and former NFL players suffering from CTE, is by definition relatively small. And you can’t very well go harvesting and sectioning brains from living players, although it was widely speculated that the former NFL linebacker Junior Seau aimed to facilitate just that outcome when he shot himself in the heart—not the head—in 2012. To hear the NFL tell it, the burden of proof is not on them to prove that football is safe; rather, the burden is on its opponents to prove that football is systematically and universally unsafe: that every case of CTE in a former player was directly caused by playing football and that football players are disproportionately likely to suffer from CTE. Casson and his committee thus cast any attempt to question the NFL’s policies as claiming to have proved just that; as, in other words, claiming improperly—-immodestly—broad implications for the existing findings. Unscientific.

In the film, Bennet Omalu says, “Everybody looked at me like, ‘Where is he from? Is he from outer space? Who is this guy? Who doesn’t know Mike Webster in Pittsburgh?” Omalu is the Nigerian-born Pittsburgh neuropathologist who happened to serve as the Allegheny County Medical Examiner when former Pittsburgh Steeler “Iron” Mike Webster died. He is an outsider in many ways: a dark black man with a Nigerian accent, a relatively low-profile public worker, and above all, not a football fan. When Webster’s body is brought into the coroner’s office, a colleague tells him, “It’s Mike Webster!” Omalu replies, “Who’s Mike Webster?” The same thing happens when another former Pittsburgh Steeler, Terry Long, commits suicide in 2005. Again, Omalu is the medical examiner on call, and again, the film makes a point of showing us, he has no idea who Long is. League of Denial casts Omalu as disinterested, a neutral party, a naïf, even. When Seau kills himself in 2012 and Omalu—now deeply professionally invested in the study of CTE—secures verbal permission to study the brain from Seau’s son Tyler, he once again stresses that he had never heard of Seau. Even in his documentary interviews, Omalu continues to mispronounce Seau’s name. “He doesn’t know anything about football,” says Steve Fainaru. But this outsider status is a scientific liability, not a strength, as the NFL succeeds in discursively making the circle of reliable modest witnesses identical to the circle of aficionados.

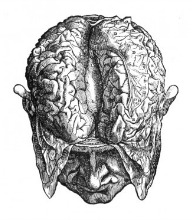

Omalu does his regularly scheduled autopsy of Webster and finds unusual patterns of tau protein deposits—the first diagnosed case of chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE) in a football player. Sharing his findings with other experts in the field, he publishes a paper on Webster’s brain and CTE in Neurosurgery. Three members of the NFL’s MBTI committee, including Casson, write to Neurosurgery, casting aspersions on the study and on Omalu’s scientific chops and demanding a retraction. The MBTI committee adds insult to injury when, in 2007, the year that Roger Goodell becomes commissioner, the league stages a major conference on brain trauma in Chicago and invites everybody who’s anybody—except for Omalu.

When Omalu flies out to study Seau’s brain, he is turned away at the last minute: The NFL gets to Tyler Seau and convinces him that Omalu is a quack, not to be trusted. The brain goes to the National Institutes of Health; “NFL doctors,” a voice-over informs us, “say the decision was made purely in the interests of science.” Of one of his many conflicts with the NFL, Omalu says to the camera in disbelief, “They insinuated I was not practicing medicine; I was practicing voodoo. Voodoo.” Drawing on a rich racist legacy that rewrites the knowledge of the colonized as superstition and, simultaneously, renders all people of color interchangeable, the NFL—and, if we are fair, others in the scientific community—made Omalu an outsider not only to football but to science.

The accusations of immodest overreach that the MBTI committee directed at Omalu also underwrote its objections to Ann McKee’s research. “I just have a problem,” says Hank Feuer, sounding like an aggrieved climate-change denier. “Ann McKee! She cannot tell me where it’s starting. We don’t know the cause and effect. We don’t know that right now. We don’t know the incidence.” McKee has not proved that playing football causes CTE, Feuer chides. But when it comes to health policy, is that the point? If we are doing something that seems remarkably correlated with early-onset dementia, massive depression, violent episodes, and abnormal deposits of tau proteins in the brain, is it necessary to definitively demonstrate causation before suspending the correlated activity? “Anecdotes are not data,” but neither are they meaningless.

To the NFL, this is dangerous logic—not scientific logic (correlation does not equal causation; anecdotes are not data) but Mom logic (don’t hurt my baby; you’ll shoot your eye out; if it’s dangerous, don’t do it). In a drawn-out interview, Omalu narrates a meeting with Joe Maroon, a distinguished neurosurgeon, member of the MBTI, and longtime brain consultant to the Pittsburgh Steelers, in which Maroon reveals why afición and science have to be identical, why Omalu’s science might lead disastrously to Mom logic and therefore not be science at all. Maroon asks Omalu if he -really understands the implications of his work, and it turns out that this is not a question about neuropathology but about football culture and those who are prone to not getting it.

And the NFL doctor at some point said to me, “Bennet, do you know the implications of what you’re doing?”

So I looked toward my left, I said, “Yeah, I think I do.”

Said, “No you don’t.” [Laughter.]

So we continued talking, talking, at some point he interrupted me again, “Bennet! Do you think you know the implications of what you’re doing?”

I said, “I, I, I think I do; I don’t know …”

He said, “No you don’t.”

So we continued talking again, then at that time he interrupted me, and I’m talking to him, I said, “okay, why don’t you tell me what the implications are.”

Said, “Okay, I’ll tell you. If ten percent of mothers in this country would begin to perceive football as a dangerous sport: that is the end of football.”

"I lied to my mom,” Michael Vick said in a 2012 television interview. “I told her the truth the day I got arraigned. I think my mom cried for four or five days straight.” Vick was convicted of dogfighting in 2007, the year of Ira Casson’s installation as MBTI committee co-chair; suspended from playing; imprisoned for two years; and subsequently declared Forbes’s most hated NFL player. Before that, he was my high school’s most celebrated alum. I never met him. We were both tracked—more so than I realized at the time. He would go on to be a professional football player, petted like a prize fighting cock (or Falcon) one minute and disgraced the next for cruelty to animals. I would go on to read classic ethnographies about “deep play.”

“I love dogs,” says Vick, a true aficionado. “Back when I was involved in those activities, I may have become more dedicated to the deep study of dogs than I was to my Falcons playbook.” The comparison between the study of dogs and the study of the Falcons playbook—the fluidity between them, the way they compete for the same mental terrain—is telling. Brenda Vick cried over her son’s dogfighting scandal; perhaps she cries over the danger of head trauma too. What does a mother know of deep play?

Of League of Denial’s many awkward moments, perhaps one of the most awkward is when McKee, a neuropathologist and co-director of the Center for the Study of Traumatic Encephalopathy at Boston University and, with Omalu, one of the film’s primary faces of opposition to the NFL’s stance on brain trauma, is forced to speak as a mom, in one of the few clips in which an interviewer audibly prompts responses.

Interviewer [off camera]: “If you had children who were eight, ten, twelve, would they play football?”

McKee: “Eight, ten, twelve? No. They would not.”

Interviewer: “Why?””

McKee: “Because…it, the way football is being played currently, that I’ve seen, it’s dangerous. It’s dangerous, and it could impact their long-term mental health. You’d only get one brain. The thing you want your kids to do most of all is succeed in life and be everything they can be and if there’s anything that may infringe on that, that may limit that, I don’t want my kids doing it.”

McKee begins her final reply slowly, taking care not to speak of football as such but rather “the way football is being played currently,” adding “that I’ve seen,” embracing a position that flags the limits of her knowledge. Of course, what McKee has “seen” is not just “the way football is being played currently” but the 46 brains of football players that she has examined in her professional capacity, 45 of which showed the tau protein deposits typical of CTE. Yet her speed and assurance gather as she completes her answer, which turns to thoughts of a child’s well-being. We have just learned of her examination of the brain of 18-year-old high school athlete Eric Pelly, whose brain already showed signs of CTE. -McKee’s own son was 18 at that time. The “I don’t want my kids doing it” with which she closes is definitive. She’s a mom, and she’s refusing permission.

McKee’s expertise and her history as a football fan are superseded by her status as a mother. “I don’t think anyone else but the wives, sisters, mothers, daughters, and Ann McKee could have forced this issue into American consciousness,” journalist Jane Leavy affirms in the film. The film goes on to describe Eleanor Perfetto’s loving advocacy for her increasingly mentally impaired husband, former Pittsburgh Steeler and San Diego Charger Ralph Wenzel. It is as moms and caretakers that women are understood to challenge the NFL, with the morally suasive force of sorrowful fin-de-siècle wives campaigning for temperance. McKee’s professional reservations about Omalu, and her ascendancy as his more rigorous (whiter? more American? more attuned to the social conventions around football?) successor, detailed in the book, are submerged in the documentary. In the end, the documentary makes McKee less a neuropathologist than the prototypical concerned mother that Omalu is accused of creating—the one who, out of concern for her children’s health, will destroy football. Likewise, the film passes in silence over Eleanor Perfetto’s Ph.D. in public health and her job as senior director of health policy for Pfizer.

In the end, then, League of Denial mobilizes mothers’ moral authority but only as moms—and thus as structural outsiders to both scientific authority and “the game,” even when those mothers hold doctorates in medical fields or, as in McKee’s case, grew up thoroughly embedded in football culture. As the film’s closing sequence reveals, moms’ concerns are superseded by the concerns of deep play, whose structuring assumptions (who’s in, who’s out) the film can demonstrate but cannot bring itself to critique. A resigned outrage characterizes former New York Giant Harry Carson’s statements about the league’s treatment of player safety issues. It is clear that he is disgusted and fears dementia and early death as a result of league’s deceptions. He feels guilt for personally dealing so many blows to Webster. His is the most oppositional voice we hear as the League of Denial closes in a montage of melancholic masculinity.

Carson’s is also the last voice to speak for football players, as the site of worry subtly shifts. “For now,” says a voice over mournful background cellos, “the future of the league and the game of football seems secure. But fundamental questions remain about how the game will be played, and who will play it.” The film stops mourning players and their families, and starts to mourn the future of “the game,” that beautiful ballet of violence. Safe now, but perhaps not for long. We have seen who is not safe: players, the women and children toward whom they are violent, sometimes as an effect of early-onset dementia and related mental illness. But the film turns to the question of whether the game—the art—is safe. “I mean, you’ve got the most popular sport in America basically on notice,” agonizes Mark Fainaru-Wada in the film’s final words. “You’ve got the very real question being asked, whether the very nature of playing the sport exposes you to brain damage, and lots of science that suggests that it can. And that raises all sorts of questions for guys who are playing in the league, guys who played in the league, moms, kids, all of us who love football.” Could we be losing football to moms? “It’s pretty scary. It’s a big deal.”