Beckett’s archive, founded at the University of Reading in 1971 by Beckett’s official biographer, James Knowlson, is spread across two continents and several universities, and contains manuscript pieces, typescript drafts and notebooks, periodical titles, news cuttings, dissertations, audio and video recordings, ephemera, posters, photographs, paintings, annotated production texts, books from Beckett’s personal library, and many signed editions. From 1996, when Knowlson’s “Damned to Fame” was published, until the arrival of The Letters of Samuel Beckett 1929-1940 in 2009, Beckett’s archive for the non-specialist had been mostly silent.

The measured release of material has multiplied the way Beckett’s work can be interpreted, transforming the image of Beckett as a leading 20th century existentialist into a historically and culturally complex figure who actively resisted a stable interpretation of his work. What the estate has accomplished through its trickle of archival material is perpetual scholarship, allowing certain numbers of comments upon a theme before new information is dangled in front of eager scholars, negating earlier arguments. With Palgrave Macmillian, Continuum, Rodopi, and Cambridge University Press all with dedicated imprints to Samuel Beckett, and The Samuel Digital Manuscript Project (the digitization of Beckett’s manuscripts along with accompanying rewrites and revisions), Beckett studies lubricates itself through the diffusion of the source material.

The Letters of Samuel Beckett are the culmination of 20 years of diligent work and service to perpetuate the author into the 21st century. The collected correspondence is being published in four volumes: the first, published in February 2009, covers the years 1929-1940; volume two, published this past September, covers 1941-1956. Volumes three and four are yet to be published. Compared with the monumental accomplishment of compiling his letters, Beckett’s published work can almost seem secondary. His is a life annotated, cross-referenced, and archived. Volume One of The Letters of Samuel Beckett 1929-1940 reveals a young writer struggling for freedom — it is no accident that his first theatrical work was titled Eleutheria — from Ireland, literary tradition, financial dependency, family, and ultimately his native English.

The second volume spans the most fecund writing period in Samuel Beckett’s life, a time he referred to as “the siege in the room.” In this lucrative and creatively fertile postwar period, Beckett wrote Waiting for Godot, his trilogy Molloy, Malone Dies, and The Unnameable; Texts for Nothing, Watt, All That Fall, Endgame, and a handful of other texts. Because of the administrative limits Beckett saddled his estate with, mainly functionary correspondence dominate the 800 pages of volume two, but the editors found a structural foothold in Beckett’s correspondence with Georges Duthuit, Matisse’s son-in-law. In these letters, Beckett is writing toward an aesthetic he can’t quite name; he is exploring the impossibility of the artist as anything other than the artist of failure. Finally, the work of his longtime friends, abstract painters Geer and Bram Van Velde, provide Beckett with a frame for his aesthetic visions, which manifested in The Unnameable: “For all that, it is still, for me a painting without precedent, in which as in no other I find what I am seeking, precisely because of this fidelity to the prison-house, this refusal of any probationary freedom. Because of that necessity of genius where he finds himself, to recognize in his hole, even as he obstinately seeks to pull himself out of it, the freedom, the high places, the light and the only gods that concern him, and that there is no escape other than partial, and even then only towards mutilation.”

Also touching on mutilation, volume two collects a lovely quibble with Simone de Beauvoir, and one sees Beckett fighting for the inclusion of both parts of his Suitein Les Temps Moderne: “You are immobilizing an existence at the very moment at which it is about to take its definitive form. There is something nightmarish about that. I find it hard to believe that matters of presentation can justify, in the eyes of the author of L’Invitee, such a mutilation.”

Along with the positive reviews and success Beckett received from Godot, he received a growing mass of fan letters, which he never relented from answering. Beckett often wrote his most profound and candid letters to strangers:

My dear Prisoner: I read and re-read your letter. Godot is from 48 or 49, I can’t remember. My last work from 50. Since then, nothing. That tells you how long I have been without words. I have never regretted it so much as now, when I need them from you. For a long time now, more or less aware of this extraordinary Luttringhausen affair, I’ve thought of the man who, in his cage, read, translated, put on my play. In all my life as man and writer, nothing like this has ever happened to me. To someone moved as I am phrases come easily, but from a sloppy way of talking not at all your style, given that I am no longer the same, and will never again be able to be the same, after what you have done, all of you. In the place where I have always found myself, where I will always find myself, turning round and round, falling over, getting up again, it is no longer wholly dark nor wholly silent. That you should have brought me such comfort is all that I can offer you as comfort. I, who am what is called free to come and go, to gorge myself, to make love, I shall not be fatuous enough to dispense to you words of wisdom. To whatever my play may have brought you, I can add this only: the huge gift you have made me by accepting it.

Though these letters often intersect with his work and allow for a wider understanding of his nuanced texts, they mainly elucidate an administratively proficient Beckett who delegated tasks to his beloved Suzanne, his longtime partner and sometime literary agent, and wrote thank-you notes to reviewers.

A letter to Donald McWhinnie shows Beckett’s genius at its best, pushing aesthetics and reinventing traditional forms. All That Fall, Beckett’s radio play for the BBC, called for animal noises and human grunts. To appease Beckett, the procurement of these sounds lead to electronic enhancements to concrete sources and eventually to the development of the BBC’s Radiophonic Workshop, “Perhaps your idea to give them the unreal quality of the other sounds [sounds produced by a human]. But this, we agreed, should develop from a realistic nucleus…could they not be distorted by some technical means?”

Beckett’s legacy has been cultivated to portray him as the apotheosis of a noncommercial artist, one who lives outside a traditional marketplace and one whose success is attributed to talent alone, a genius without any trifling for success. Although Beckett is a writer “damned to fame,” who valued his private life and wished for no middling upon it, who wrote in a letter in volume one, “if we must make money let it at all costs be at something other than writing.” In the footnotes to volume two, at least four archaic turns of phrase are explicated as “payment.”

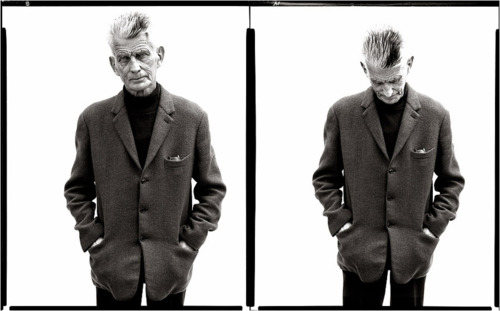

It’s befitting that an author who saw fame as an intrusion would have an estate positioned to evolve and transform and litigate with ease. The estate has preserved a manufactured and remanufactured image of the author, crafting the icon of the monastic Beckett and blocking publication and citation of many letters that might portray him as something other than the official emblem, splashed all over Grove Press’s reissues: the stark eyes and aquiline nose dug into a granite face.

The Beckett evoked is the static, humanistic interpretation that was prevalent during the middle 20th century, yet Beckett’s willing engagement with technology in the second volume’s letters retains the verve displayed in the first volume, and whether directly related to the texts or not, one hopes the editors will publish more letters that examine that trend and offer the reader a new way of framing our encounters not only with Beckett’s challenging body of work, but with a great deal of avant-garde writing generally.

For beyond being a strategy for guarding Beckett’s image and exploiting the letters to the fullest extent economically, the measured release of Beckett’s archive, by coinciding with the rise of new media, may help create a new type of Beckett audience, one that may not actually go to the theater to see his plays or watch his film, or even read his prose or poetry. This new participant is the user, one who encounters Beckett’s work first outside of the traditional forms, in letters or any digital media. An open-source Beckett of this sort is much more dynamic, and the viscosity of information flowing down from the archive, slow or fast as that may be, can be amended and become a resource to future readers.