Imagine you are driving home from a long day one Friday and little ghoul-faced vampires, witches, and sheet-masked bodies start to dart around your car. They slow the traffic and swallow up your vehicle in a wave. They wade into the street and whack your sedan with buckets full of candy. A few of the gutsier ones press their faces up against the car windows and cackle at you, their little voices become a taunt, and their painted faces smear against the glass in some orgiastic tradition. It is like any other Halloween of the year, and yet it never ceases to be unnerving. Therein lies that unsettling fact: Whether under control or not, children can be terrifying.

There is a similar scene in Lynne Ramsay’s new film We Need to Talk About Kevin. Eva Khatchadourian is caught in a Halloween frenzy, made even more chilling by the use of Buddy Holly’s “Everyday” on the soundtrack. She manages to make it into her house, down an old glass of red wine, and collapse into a corner as the children surround and pound on her door yelling “trick or treat.”

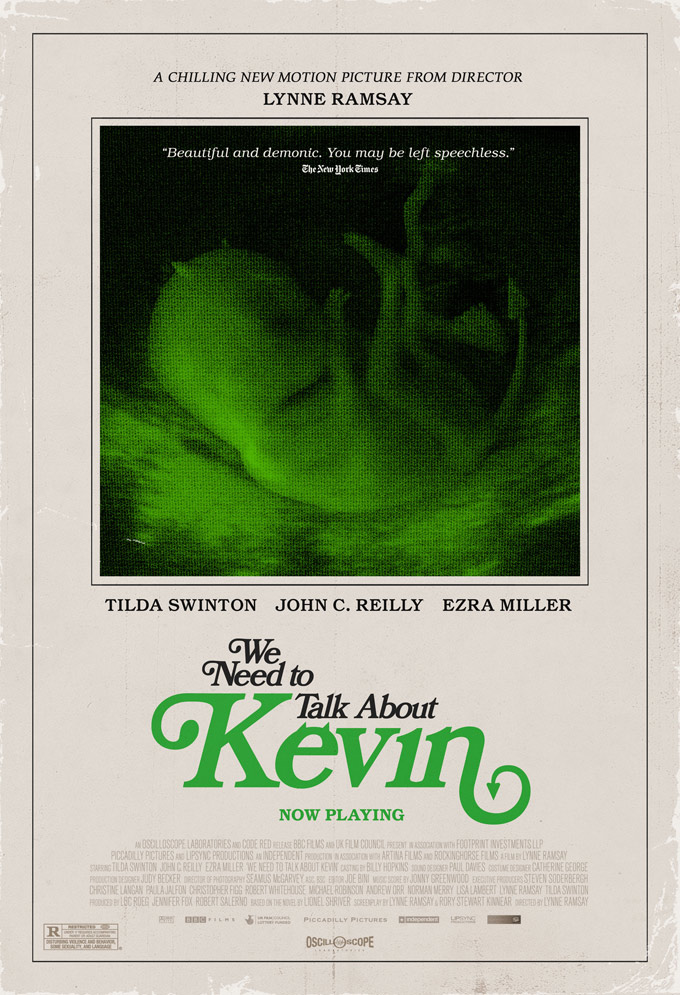

Ramsay’s film is an adaptation of Lionel Shriver’s 2003 novel of the same name. It takes place in the wake of a school massacre executed by the Kevin we all need to talk about. Tilda Swinton is perfectly cast as Eva, the cool, statuesque mother softened — or made pathetic — by her son’s horrendous crimes and the shame she has to suffer for them. John C. Reilly is the affable and oblivious Franklin, who believes his son can do no wrong. Ezra Miller plays the teenage Kevin at the apex of his sociopathic tendencies, and Miller really does "play" Kevin: He oozes such charisma that he seems to be having just a little too much fun.

Set post-massacre, we find Kevin’s mother alone, a shell of her former self, consigned to a new life of doubt and forced reflection. Kevin has always been a strange child, we learn, through the slanted view of mother Eva’s recalling that makes up much of the film’s running time. But interest in the Kevin character is largely propelled by what Alyssa Rosenberg calls “the Bad Thing” in an article she wrote about the novel for The Atlantic. “The novel exploits and forces us to acknowledge our greedy desire to see horrible things happen,” Rosenberg writes.

It would be delicious to watch the film without any exposure whatsoever to the story, to let “the Bad Thing” dawn on you slowly, because, despite film being a perfect medium to satisfy our scopophilic viciousness, Ramsay doesn’t indulge our wishes so explicitly. Instead, her skillful filmmaking whittles away at the marrow of the characters in expert use of parallel imagery. The film is a precisely crafted visual feast, and if you’re familiar with Lynne Ramsay’s cinematographic style, from features such as Ratcatcher and Morvern Callar, Kevin is perhaps its apotheosis. The film is constructed with a series of interweaving scenes free of chronology, with Eva as the conduit. You can never be sure the time or place of the scenes. Instead, it creates a pool of images the viewer must wade through: the orgiastic opening of the La Tomatina festival in Spain, the red-paint-splattered house that Eva’s been consigned to live in, the way Kevin bites off his fingernails and lines them up in his jail cell, Eva’s own sacrificial meal of smashed eggs with the shells in them. The film delays the desire to see Kevin act out the Bad Thing by imbuing every banal action and moment in the film with portentous weight.

I couldn’t help but think of America’s favorite Kevin, Macaulay Culkin’s invocation of him in the early Home Alone series. Culkin’s Kevin is the black sheep of an absurdly large family that is corralling everyone together for a Christmas trip abroad. Kevin is the poster image for childish rebellion: Everyone already hates or is irritated by him, so he plays along by not making anything easier and is accidentally forgotten. Finding himself alone in the morning, Kevin is shocked and a bit scared. “I made my family disappear,” he says to himself, in the cavernous house he’s been stranded in. It takes him only a second to realize the repercussions of this statement and he stands, wiggling his eyebrows, emboldened: “I made my family disappear!”

This Kevin, the kind of Kevin parents will let their children watch for ages in the weeks before and after Christmas, was also a bit of a sociopath. He revelled in his family’s departure. He ransacked the house. He played war with a pair of very laughable villains, in which he showed a prowess with scare tactics that matched theirs. He loved every minute of it, all the while his mother, wringing her hands, took pains to return from France, repeating the mantra “I’m a horrible mother” again and again. The Home Alone Kevin has always been a hero of sorts, not a bad boy. He had villains to fight against, and his adventure allowed his family’s worry and negligence to fade into the background. He may have been a bit of a sociopath, but his mother worried about him, and he was so cute, right?

Ramsay’s Kevin is one we don’t want to remember. After Eva papers a room with maps and images from her years abroad, Kevin says, “These squiggly squares of paper. They’re dumb,” and sprays paint throughout his mother’s room of her own. When Eva and Franklin decide to have a second child, Kevin is petulant in the creepy, reserved way he internalizes his anger. She tries to describe to him, at age 7, how “Mama Bear and Daddy Bear” went about creating his sister. “You mean fucking?” he says. He looks his mother straight in the eye, methodically breaking crayons, and gives her a steely argument for why he will never accommodate a little sister: "Just because you're used to something doesn't mean you like it. You're used to me." We would like to forget this Kevin, but we cannot. Nor can Eva. She is trying to move on with her life but is forever wedded to the Bad Thing.

It is her own self-punishment to stay in the town where the Bad Thing happened instead of fleeing, as is her wont. Through a series of dreamlike flashbacks, Eva’s present life is woven into her past life, and we learn she’s been demoted on a number of levels. Once a respected travel writer, Eva now lives in a small town in upstate New York, applying for menial work at a depressing lower-tier agency. “I don’t really care who you are or what you done — so long as you can type and file you can have this job,” says a potential employer to Eva near the beginning of the film.

Even before Kevin is born you sense a subtle disgust on Eva’s part at the child inside her. Perhaps it’s the idea of motherhood in general. So much of the movie’s silence is woven into assumed understanding of Eva’s plight. Ramsay has expertise in rendering a single woman’s perverse grief on a couch to a stellar soundtrack, as witnessed in Morvern Callar. It can be easy to forget the protagonist’s own culpability as we surrender to her force in directing the story. During one rare mother-and-son outing, Eva lets out a litany at the miniature golf course: “Fat people are always eating. It’s food. They’re fat because they eat the wrong food.” Kevin snarls at his mother, “You know, you can be kind of harsh sometimes. Wonder where I got it?”

This is the question that haunts Eva, where Kevin “got” the Bad Thing, because she feels, as anyone would in the situation, to blame. There’s really no place in the popular imagination for bad mothers, for dissatisfied mothers made unhappy by their children. There are a slew of articles about how difficult it is to be a mother in the modern world, to balance a career with motherhood, or to stay at home forgoing other aspirations. But little sympathy is extolled for the subtle embarrassments and horrors of children, those who cling a little too hard to your car on a Halloween evening. The mother is expected to love unconditionally, blindly, and stupidly and be made happy by the effort.

The pre-massacre Eva was not exactly sympathetic in these maternal respects. She’s a successful writer and businesswoman. She lives in a downtown loft in New York with a doting husband, who finds it his responsibility to move the family into a sprawling, minimalist house upstate. And on top of it all, Eva’s kind of a bitch. In Shriver’s novel, Eva relates her encounter with a bereaved mother after the massacre at the grocery store:

I imagine you can grieve as efficiently with chocolate as with tap water.… Besides there are women who keep themselves sleek and smartly turned out less to please a spouse than to keep up with a daughter, and, thanks to us, she lacks that incentive these days.

It takes something beyond starry-eyed appreciation for Swinton’s steely yet sad character to see to this literary core, there in the first pages of Shriver’s book, that a sort of wicked and “Bad Thing” exists in most of us, latent or expressed. Eva’s harshness seems to flourish and develop after she loses everything: She perfects her own punishment.

In the aftermath of Kevin’s Bad Thing, the moral weight of the story entirely falls on the shoulders of the mother, not her criminal son. You can produce a psychopath even if you are a good mother. What we learn is that Eva was not a good mother, or even an okay mother. However, the reality is that even if the Eva and Franklin parental unit did talk about Kevin, they would not have been able to stop him from killing his classmates and teachers. Good parents or bad, they could never have conceived the plans he had in mind.

The problem of the child psychopath is about where to place the blame, and this is never perfectly clear. For one, children are terrifying: in their newness, in their mocking report of the results of nature vs. nurture, in their callow and perceptive insults. There are so many unnerving and complicated cases of parents who were wholly oblivious to their children’s often fatal tendencies. Perhaps part of the confusion is obliviousness, for both the public and the parents. In Home Alone Mrs. McCallister traverses 4,000 miles while beating herself up for forgetting her son. In We Need to Talk About Kevin there is direct identification between child and parent, which gives the story its resonant tension.

Eva is not unlike her son, and perhaps that’s why she’s never liked him and why he hates her. Kevin and Eva share a similar haircut: blue-black shorn hair, the wispy bits cutting like little knives across their cheeks. They both desire for control of every situation, whether through childproof cabinet ties or bike locks. They share a common distaste for the whimsy and kindness of others, and they equally hate the other for seeing through them. It is hard to not hear Ramsay’s recurring choice of song “Mother’s Last Words to Her Son” as the perfect leitmotif:

I never can forget the day

When my dear mother did sweetly say

You are leaving, my darling boy,

You always have been your mother's joy.

As the film moves on, two years past his incarceration date, we learn that Eva is preparing Kevin’s room for his return: ironing his shirts, placing his favorite childhood book, Robin Hood, on the night table. It becomes difficult to tell who’s more deluded: the son, “out of his head on Prozac” in prison for killing his classmates and a teacher, or the mother, bearing the scarlet letter, whether it’s paint an upset townsman has thrown on her house or her methodically and dutifully scraping it off her fingernails and hair during the course of the film. Ultimately Kevin and Eva belong together: Separated by bars or outside of them, because they hate each other or because they are each other, because they both made their families disappear or because they are now left with nothing but each other.