The last three pages of Hungarian author László Krasznahorkai’s novel The Melancholy of Resistance describe, in precise detail, the step by step process of the decomposition of a corpse as if it were some kind of cosmic battle--the sinews and fibers and bones and blood resisting the inevitable victory of the body’s own forces of decay. There’s a fragment of this passage that reads as a mission statement of sorts, a means of understanding not only The Melancholy of Resistance, but also Krasznahorkai’s entire body of work: “…and when, after a long and stiff resistance, the remaining tissue, cartilage and finally the bone gave up the hopeless struggle, nothing remained and yet not one atom had been lost.” Everything is gone, but it is all the same as it ever was. “It passes,” the book’s epigraph reads, “but it does not pass away.”

The decay of the corpse in The Melancholy of Resistance emerges as a microcosmic metaphor for the larger forces of inexorable decay present in the world. It is an apocalypse of the body meant to suggest the global apocalypse. Susan Sontag (who has blurbed about every one of Krasznahorkai’s books) called him “the contemporary Hungarian master of apocalypse.” Apocalypse is Krasznahorkai’s oeuvre described in a single word. But just what kind of apocalypse does Krasznahorkai predict?

For an answer, we can turn to the author’s latest release in English, The Last Wolf & Herman. The book, a collection of two short stories, acts as a distillation of Krasznahorkai’s essential themes: apocalypse and the death of innocent violence.

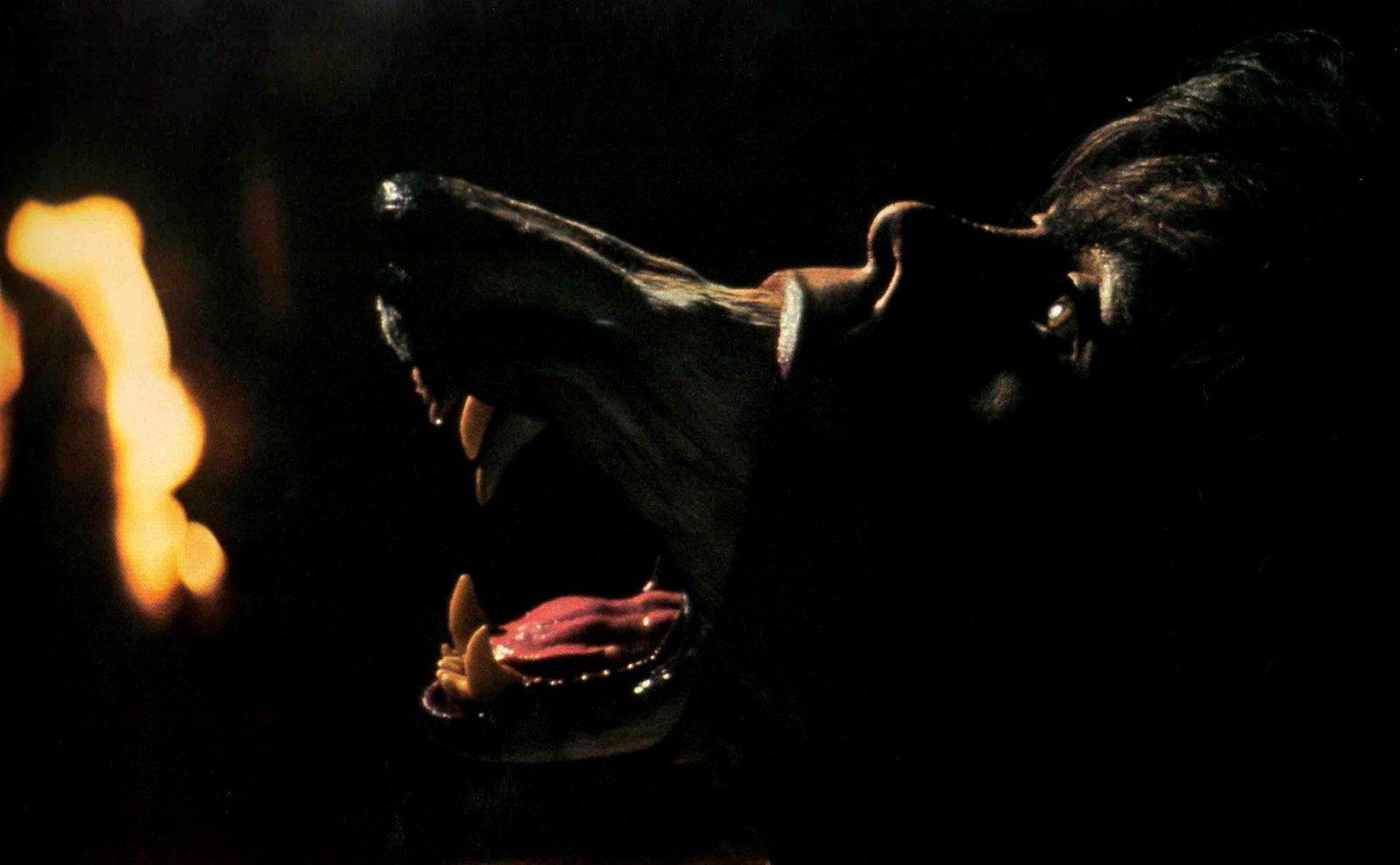

In the first story, “The Last Wolf,” Krasznahorkai has written what can be called, for lack of a better word, a sad story. Often, there is something about wolves in literature, something so wounding, so terribly tragic, that their mere presence in a story signals that we are about to be left desolate, frustrated, enraged. Wolves are often deployed as symbols of pride and independence, and it is their subjugation that incenses us. Consider the first third of Cormac McCarthy’s The Crossing, or Jack London’s White Fang (before the happy ending).

Krasznahorkai’s wolf story takes place in a dilapidated Berlin bar, where a washed-up philosophy professor recounts a tale--in a long, 76-page sentence--to a Hungarian bartender. The professor, a destitute man who is “finished with thinking,” is invited to the Spanish region of Extremadura to write something, anything, to “give voice to the flowering of Extremadura, this once historical wasteland.” The professor agrees to the request and picks as his topic the story of the last wolf, which had allegedly been killed by a lobero (wolf hunter) in 1983. When he arrives to Extremadura he is struck by the stark barren beauty, which the population is eager to modernize. “It would be awful telling these good people the fate that awaited them,” Krasznahorkai writes, “[The professor] was all too aware of how the world would break in on Extremadura.” It is a process already underway, and we see the death of the last wolf--which, we learn, was in 1993, not 1983--as the harbinger of this change.

The second-to-last wolf, which is pregnant, is struck dead by a car. Unable to cross the road in time because of her swollen belly, the wolf is killed by modernity precisely because she is a symbol of continuation. But after hope, one might still have pride, and here is the greatest wound of the story: the very last wolf, thought to have escaped to Portugal, is shot dead on his old territory as he was roaming alone, too proud to leave his home, too innocent to know another way.

The violence of animals, as contrasted with the violence of humans, is always innocent--they cannot behave otherwise. This adherence to their nature means that they cannot be homogenized and assimilated into the fold of suburbia. Even while alive, the town’s population attempts assimilation by anthropomorphizing the wolves, a sublimation and gentrification of animal difference. Similarly, poor taste and filth imply another way, a natural, innocent, rebellion against order. The last wolf, like pre-suburbanized Extremadura, was innocent and autonomous, and therefore had to die.

“Herman,” which in its prose is the more traditional of the two stories, also focuses on the death of animals. In the first section, a veteran gamekeeper (the titular Herman) kills an array of “noxious predators” and “useful game.” “Noxious” and “useful” are the only two possible categories of animals delineated by the township for which Herman works--the very act of grouping, of distinguishing between creatures on the basis of their use-value is among the most sinister aspects of the entire story. The setting of “Herman” is, unlike the setting of “The Last Wolf,” already suburban, already cleansed of difference. It is only when one patch of hunting land goes uncared for and allowed to regain its “noxious predators” that Herman’s services are requested. An expert in his craft, Herman, employing an array of grisly traps, quickly succeeds in reducing the number of “noxious predators” in the forest. But after a dream in which Herman sees “the carrion pit in the distance…slowly approaching the pit, he becomes aware of a certain hideous stirring…he hears frightful nauseating sounds of slurping and sliding, popping and splaying, until…at last he must confront in the depths of the pit the enormous putrescent hairy mass of dead meat quivering like jelly,” he realizes the essential difference between human and animal. Unlike the animal, our violence is a choice. Herman’s revelation is not that animals (including humans) are all the same--this would be trite--but rather that all animals are autonomous, and therefore resist assimilation.

“Herman” ends much like one would expect it to: Herman seeks justice for the hunted animals by turning his traps on the town’s populace, and for his rebellion he is killed. It is in the second version of “Herman,” titled “The Death of a Craft,” that we see the story from the perspective of the town, and where we see Herman’s rebellion for what it is: useless. His rebellion is mythologized and utilized by the townspeople for their own ends (in one case, as a religious message against sin; in another, as entertainment; in yet another, the carcasses that Herman leaves around town are frozen for later consumption). Rebellion in Krasznahorkai’s work is always assimilated. Herman, like the wolves, is the last of his kind, his death being “the irrevocable end of…a profession, an ancient craft.” The death of the last wolf, the death of Herman--this is where the world ends, this is where heterogeneity is destroyed.

The ending of Satantango (1985), Krasznahorkai’s first novel, offers another nice way into the stories. Satantango tells the story of the greedy, conniving, wretched inhabitants of a desolate collective farm somewhere in Hungary. During a particularly heavy and unceasing rain storm which has rendered the roads to the nearby town entirely inaccessible, the inhabitants of the farm come together in a bar to drunkenly await the arrival of Irimiás, a mysterious figure long presumed dead and whose return they believe will bring an alleviation of their largely self-made misery. The characters of Satantango, after their “apocalypse” (the return and then departure of Irimiás, who we learn is actually an agent of the secret police), all end up removed from the collective farm, scattered throughout the suburbs. After dispersing the residents of the collective, Irimiás drives back into town to file a report with the secret police about the newly incorporated citizens. On the road to the secret police headquarters, Irimiás’s sidekick Petrina says: “Things that begin badly, end badly. Everything’s fine in the middle, it’s the end you need to worry about.” If we take Irimiás’s response as any indication, things have ended badly--“Irimiás was looking up the road, not saying anything. He felt no pride now that it was all settled. His eyes stared dully ahead, his face was gray…He saw the neat houses on either side of the street. The gardens. The crooked gates. The chimneys belching smoke. He felt neither hatred nor disgust.” The suburbs here are the endpoint of apocalypse, the “world to come.” And in the suburbs, there is neither hatred nor disgust, just grey, just nothing. This is how things end in Satantango, nobody is saved, nobody is redeemed, nor are they damned. That the misery in The Last Wolf & Herman is what awaits is precisely the message.

Many critics--Adam Thirwell of the New York Review of Books for instance--have situated Satantango, and other Krasznahorkai works (particularly The Melancholy of Resistance) within the context of Krasznahorkai’s native Hungary. The two novels were written while Hungary was still under communist rule, and the lurking presence of authoritarianism (which, under the thumb of the Soviet Union, was particularly repressive and cruel, especially in the immediate aftermath of Hungary’s 1956 Revolution) runs through much of the author’s work. The misery of homogeneity, too, is a defining feature of the former communist countries, where a sort of sameness was an explicit goal. It is worth noting as well that Krasznahorkai continues to spend a great deal of time in Hungary, which, like many of the other former communist countries, seems to be falling back into the authoritarianism that it never truly escaped. Krasznahorkai himself has affirmed that his home country has, like the world of his novels, never emerged from its misery. In an interview with The Guardian, he stated that before the fall of the Berlin Wall “the world in Hungary was absolutely abnormal and unbearable, and after 1989 it was normal and unbearable.”

But there is a limit to these historical readings, precisely because the misery of Krasznahorkai’s world is not dependent upon time or place. (In an interview with The Millions, he says, “The idea of a political message in Satantango was as far from my mind as the Soviet empire itself.”) The heroes of his novel War and War for example, flee through time and space, looking only for some peace. But again and again, war, or simply the threat of war, follows on their heels and their own apocalypse is repeated ad infinitum--apocalypse being an immutable condition of existence. The world Krasznahorkai depicts is not limited to communist Eastern Europe, but also describes our own.

Krasznahorkai’s apocalypse, in the end, does not take the form of a great disaster. Instead, it revels slowly in the destruction of distinction, the homogenization of the world. This is the horrible realization at the heart of Krasznahorkai’s books: the day of judgement has already passed, there is no other hell than this.