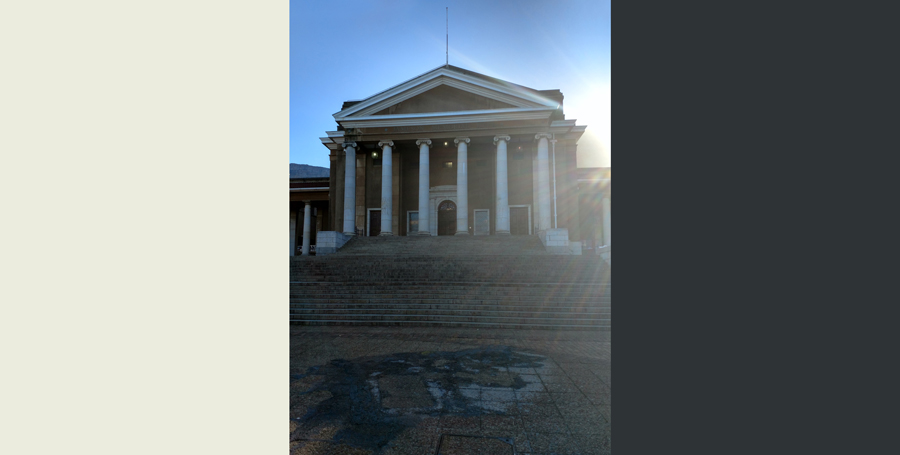

As I walked down University Avenue on an early, empty, bitter winter morning at the University of Cape Town (UCT), chants echoed in my ear—protest songs, the crackling of burning tires, and the bang and boom of bullets and stun grenades. Patches of charred concrete and tar sat tucked against the backdrop of the main hall, which stood tall, a pantheon looking out onto the city. The contestation over the heavy stone that frames this institution rages on, in open defiance of its declaration of superiority.

The uprisings of 2015 and 2016, particularly those under the banner of #FeesMustFall, propelled an urgency, vibrancy, and militancy across many South African campuses in debates over the nation’s liberation narrative and the role and future of universities in one of the most unequal societies on earth. Over 20 years after the formal fall of the Apartheid regime, the inability of the mass democratic movement to use its new constitutional democracy to address the historical and ongoing impact of land dispossession, unequal education and healthcare institutions, and other ridges within our society has brought South Africa from its hopeful, transitional era to a time of resentment, decay, self-enrichment, and pessimism. The “Must Fall” movement and its relationship to the university as a site of struggle offers a glimpse into some colliding historical trajectories, opportunities for subverting and mobilizing incompletely decolonized institutions like universities and constitutional democracies to build alternatives. We can begin to consider the “Must Fall” movements, while emerging from university campuses, as dynamic, messy terrains and sites of conflicts of the “interpersonal,” “national,” and “global.” Paradoxically, the call for what “Must Fall” shows the importance of inquiry, engagement, and mobilization as constructive support to enable the emergence of alternatives to the oppressive, exploitative, and extractive status quo.

Since the moment UCT’s central campus administration building was occupied in March 2015 for #RhodesMustFall, university researchers, public intellectuals, and vice chancellors have gone to great lengths to define, classify, and abstract the conditions of the “Must Fall” movement. The South African student protesters are often described and depicted as large masses—led by charismatic leaders, adorned in familiar banners, and met with police confrontation. What gets missed with this popular protest iconography is the notion that the people participating in these protests had ideas, dreams, debates, and theorizations. From my experience in the movement, participating in lectures (often with visiting activist scholars) has formed an important pillar for sustaining and building the movement. Packed lecture halls, loud choruses of protest songs, and passionate rebuttals are as much a part of “Must Fall” as the mass strike action where it garnered its infamy. Out of the countless events during this period, I reflect on a number of contributions put forward by activist-scholars directed at the South African student movement—not only to highlight and tackle the ideas they put forward but also to emphasize and complicate our collective understanding of how intellectual engagement, political action, and theory are moving through time and space at this juncture in history.

At the University of South Africa’s eighth Thabo Mbeki Africa Day, scholar Mahmood Mamdani delivered a public lecture titled “Africa and the Changing World,” engaging present and historical debates on universities in Africa particularly as they relate to decolonization and globalization. Mamdani anchored his lecture on some of the key debates around the “role of the university” in early postindependence moments. Two universities were described as broadly representing two contrasting visions: the older Makerere University in Uganda (est. 1922) represents the colonial university as the home of the “universal scholar,” and the University of Dar es Salaam in Tanzania (est. 1970, after independence) represents the nationalist university as the home of the public intellectual. Mamdani then turned to the independent Pan-African research organization Council for the Development of Social Science Research in Africa (CODESRIA, est. 1973), headquartered in Senegal. As a supranational institution, CODESRIA was formalized through a founding charter that evolved into a General Assembly for its members, forming the highest decision-making body, and a number of standing committees dealing with specific areas of interest.

In the wake of the Must Fall movements, it is crucial to remember that these academic institutions were built with the energy and hope of the national independence era of the last wave of decolonization movements after the Second World War. In detailing the relationship between these movements and the often contested “role of the university,” Mamdani provoked his interlocutors in South Africa to engage with the mass mobilization both within and beyond universities by agitating for and consolidating curriculum reforms and institutional shifts. This opens up the possibility of understanding the numerous emerging “Must Fall” movements in South Africa as not simply campus movements about singular issues, such as student debt, but also containing the opportunity to sustain the mass mobilization necessary to address broader and fundamental demands for change and a better future.

At the University of Cape Town in mid-2015, the #RhodesMustFall movement’s strikes and occupations called for the removal of a statue of the infamous colonial mining mogul Cecil John Rhodes. What is often forgotten is that the occupation that ultimately led to the statue’s removal consisted of wide-ranging demands bringing together many people and groups marginalized within the university community. Among other connected issues, those demands included: expanding financial aid, increasing benefits for workers, ending the use of labor-brokering practices, the removal of symbolism glorifying UCT’s colonial heritage, curriculum reform in opposition to Eurocentrism, and representation for Black academics.

During this period we were incredibly fortunate to be addressed by a number of academics, including Amina Mama, the African feminist, professor, and cofounder of Feminist Africa, who had founded the African Gender Institute at UCT. In her speech, Mama reaffirmed the importance of challenging the historical legacy of colonialism within educational institutions and discussed her difficult experience working in UCT’s hostile institutional climate. She attributed her decision to come to UCT to a deep interest and investment in helping to establish an African—regional and continental—gender institute. As Mama’s tenure began through a deep engagement in contexts where women were engaged in intense struggle, she noted the difficulties she and her colleagues had experienced in putting gender studies on the intellectual agenda of the continental network established by CODESRIA.

Reflecting on her time at the institution, she remarked on a strong push from UCT to assert a strict disciplinary focus, using administrative and financial instruments to carefully demarcate the boundaries of “acceptable” scholarship, making it increasingly difficult to sustain relationships among research, theory, teaching, and community engagement. The university has consistently attempted to curtail the growth of the African Gender Institute and the Center for African Studies, and even close the latter. Crucially, Mama’s address centered the realities and difficulties surrounding harsh funding climates that constrain the possibilities for leveraging the university space as a site of struggle in the present context of neoliberalism and permanent austerity. Mama’s statements reverberated as a call to “dig in our heels” and prepare for the long, arduous task of not simply raising issues through confrontation but building networks of solidarity and resistance.

It was prescient advice. Just two years later saw massive fracturing and splintering within the student movement at UCT. It was in this context that UCLA professor Robin D. G. Kelley delivered a seminar titled “The Black Radical Imagination: A Different Way Out,” in June, hosted by the Centre for African Studies. Kelley’s discussion pivoted on the consistent assertion of the role of popular mass struggle in relation to the Black radical tradition. Kelley reflected on the student-driven publication UFAHAMU, which began with an activist orientation and engaged with African and Afro-diasporic debates on radical politics. UFAHAMU published content ranging from overtly militant and activist-oriented to academic contributions, and it housed essays from the likes of Walter Rodney and Ali Mazrui, both of whom were cited in Mamdani’s earlier-cited address as central figures in the debates at Dar es Salaam and Makerere. Kelley called on us to continue to strengthen transnational links and awareness within these learning communities.

Tracing this historical link between militancy and academic work, I began to see it as absent by comparison today. While scholarship in postcolonial, African, Middle Eastern, ethnic, and critical race studies has rapidly expanded in form and content, the relationship to mass movements is often relegated to the analysis of the academic witness, for publishing pending review. Kelley closed by emphasizing the need to acknowledge and explore the limitations of the university as a space while taking seriously the historical and existing efforts to extend the boundaries of the elite university space through the support, and often fugitive planning, of popular education initiatives.

Following from Kelley’s thread, Pathways to Free Education, a popular education collective emerging out of UCT, published “Third World Education & Social Welfare Programmes” in August 2017. Pathways featured an interview conducted between Donna Murch, a professor at Rutgers University, and Khadija Khan, a Pathways collective member. Murch draws attention to the 1960 California Master Plan for Higher Education, which made state-funded secondary education tuition-free. This reform broadened access to institutions such as Merritt College, which several of the soon-to-be Black Panther founders attended.

It was within these institutions that Black populations gained access to radical texts from all over the world. Murch discusses the later formation of liberation schools alongside free breakfast schemes, forming part of the broader “survival pending revolution” programs, where women’s labor within the movement was central. These historical trajectories speak to the importance of understanding education not just in terms of the fight to broaden access, increase financial support, and consolidate gains within a paradigm of social democracy, but rather as containing the potential to blow open the possibilities for something different.

This can be seen in the contemporary Caribbean, where long, massive strikes at the University of Puerto Rico have stood firm in the struggle to oppose devastating austerity measures imposed by the United States Congress and invigorated broader, renewed calls for political independence for the island. Leveraging off the buildup to the 2017 French presidential elections, French Guiana mounted a general strike involving over 37 labor unions and student associations, demanding over €2.5 billion for the provision of basic services. Both of these contexts demonstrate that in today’s struggles, organized labor and the participation of students are a consistent feature in the fight against the onslaught of neoliberalism.

While underreported, organized labor both on South African campuses and in broader society has played a significant role in what has broadly been categorized as the “Must Fall” student movements. Of course, there continue to be tensions along lines of ideology, strategy, and tactics. On the one hand, many call for the death of the “Rainbow Nation” and notions of liberal nonracialism premised on permanent forgiveness for the crime of Apartheid and its accomplices. On the other hand, while wide-ranging solidarity consistently demanded, it remains unclear what dreams and programs stand to replace the fading mirage of Mandela’s liberated South Africa. As we stand at a moment on the verge of self-definition, bearing witness to a protracted social explosion, the death of the Rainbow Nation is an opportunity for healing, revolution, and perhaps calamity, great loss, and sacrifice. Standing alongside the charred concrete and tar below the Rhodes pantheon cast in heavy stone, I remain convinced that no matter what happens, the university will have a role to play—for better or worse. As the calls continue to ring for what next “Must Fall,” the struggle for what must emerge continues. It will not arrive through condescension and bad faith dialogues that ask, “What do the protesters want?” or “What is even their vision?” Instead our dreams and nightmares will be forged in the fires sparked by the friction of our paradoxical realities coming to a head.

A luta continua