When a father dies, you are left with at once so many stories and never enough.

when Kristeva speaks about a person's (be he or she artist or analysand) relation to a mother who is entirely accessible and evident in a speech without limits, or a father who is only too visible on the precision and order of every paragraph, it is in the psychoanalytic sense of the dynamic interaction between the semiotic and the symbolic that this should be understood.

— John Lechte on Julia Kristeva

When my father died I lost my western reference point, which is strange: I never knew where he came from. It was sudden. We’d said goodbye at the airport in Athens one month before, which made sense. This was a city that became home when I was barely eighteen: I landed just days after 9/11, one year younger than he was when he landed in Hong Kong after answering a recruitment advert for the Hong Kong Colonial Police Force to do, I presume, the same thing I did—make a life somewhere. Two weeks later, he was gone, never to live on UK soil again. I think it was 1964.

He always said he never felt English. The reason, as I later found out, was that he was adopted—a World War II baby: his birthday was 14 September 1945. My mother told me once that he thought he might have been Indian at one point, which is why he came to Asia, though in truth, he looked Mediterranean. I think it bothered him, deep down: not knowing where he came from, or why his parents gave him up, but he never wanted to find out what his origins were; he never even talked about it. Hong Kong suited him, though. He learned its ways. Married its women. Had children. He made the traditional Chinese New Year turnip cake better than anyone and always knew how to clean out at Mahjong. He spoke fluent Cantonese with an English accent. The people at the market who let him cut his own meat with a bandsaw always called him “uncle.”

I wasn’t surprised when he told me that parts of Athens reminded him of Hong Kong in the seventies and eighties. (After his third visit, he said Greece was one of the only places in the world he would ever come back to.) One of my earliest memories of the city was working in a popular bar with a bevy of women—we worked for hours a night, serving non-stop, three behind a narrow bar, bumping into each other regularly throughout the shift. I’d say sorry every time until my co-worker turned around and told me off. “Siga!” she cried, which translates terribly into “slowly” and more accurately into “big deal.” “You’re so English,” she laughed; she also told me never to say sorry again.

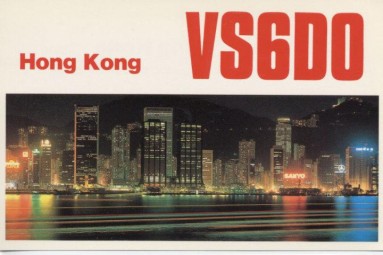

When someone dies, you are left with at once so many stories but not enough. One of my favorites is when father was a cadet in Hong Kong and everyone had assembled downstairs one afternoon for an exercise, but he stayed in his dorm to work on his radio. Somehow, his transmission synched with the loudspeakers in the courtyard below, so that, as I always imagine it, a scratching, ghostly Morse code replaced the silence. You see, Ham Radio—what you might call a pre-internet communication network, or what is more commonly known as amateur radio—was a lifelong passion, and he became quite the celebrity in the Ham world in the 70s and 80s. In an article for Radio Sporting, Bill Tippett wrote: “Hong Kong is one of those exotic cities in the world that has always intrigued me. Visions of smugglers, Suzy Wong and VS6DO’s signal on Top Band all come to mind!”

That was his call sign: VS6DO. It was one of the loudest calls coming out of South-East Asia on the 80- and 160-meter-bands at the time. This was achieved through two things: homebrew equipment he built so meticulously that Hams would travel to Hong Kong just to see it, and the fact that dad chose to live in a specific government block perfectly located on Broadcast Drive because of its suitability for transmission. (Local radio and television stations were based in the area, as was the cemetery where my Chinese ancestors are buried, which we would visit two to three times a year as per Cantonese custom, which includes buying paper money, gold and other daily items and burning them so that they reach our loved ones in the other world, rematerializing into form once the smoke has crossed over.)

He would call out his sign over and over again, starting with the standard “Seek You” or “CQ,” followed by “victor-sierra-six-delta-ontario.” This all happened from my brother’s room, which doubled as a radio shack—a fact that eventually drove my brother to move his bed into a closet. As kids, we joined in the thrill of making the call and receiving the crackled responses as they came through; voices carried on low waves, over vast distances, whose clarity depended on the physical and climatic conditions the wave travelled through. The game, in this sense, was to see how far your voice would go. For a time, it was an obsession for my father: so much so, my first words were CQ. (He called me that for the rest of his life.) Years later, I would log on to ICQ, then Jitter Chat, Global Chat, and Geocities—I suppose in this sense, moving to Athens on a whim when I was seventeen was a logical progression.

The lists I have seen from his logbook record connections made everywhere and anywhere in the world. There were times he would tell people to “foxtrot Oscar” or “get off [his] frequency” because they were blocking his aim. Other times, he would engage in conversations with friends like our uncle Aki, who he met on air. Aki came to visit a number of times; he even tried—and failed—to teach me how to hold chopsticks properly. (I still can’t.) Photos from the period show my dad with Ham friends who might have been Sunday gamers today. When connections are made, Hams send their personal call card to a QSL manager so they can verify the connection—the QSL manager is someone who is registered with a centralized amateur radio association (QSL stands for the Q code: confirmation of receipt). One QSL card has a picture of dad on it in his early thirties, sitting with his homebrew like a boss.

But he was no taipan, either. Dad was a member of a very particular generation: a crop of western baby-boomers who emerged as the imperial age—as we historically understand it—continued to unravel even in 1999, when Macau, rented in 1557, was transferred from Portuguese to Chinese rule. They were kids when the Cultural Revolution started in 1966—barely in their twenties. You might say they were the privileged flipside of a new wave of immigrants into Hong Kong divided between expats and refugees fleeing to this tiny sanctuary on the south coastal tip of the Chinese mainland to escape communist rule. I once heard a story about gunshots flying past their heads as they patrolled the border. None of them, I am sure, really knew what they were getting into, but they had nothing to lose, unlike the Chinese who came through; many had just lost everything.

My Chinese grandfather—now almost in his nineties—only told me once about his escape to Hong Kong when the Japanese invaded China: he had to run back when the Red Army arrived in the city in December 1941. Back on the mainland, he worked in a factory that I think made bullets—he has this story of being in the jungle and eating tiger for the first time (“It tasted like chicken!”)—and returned to Hong Kong after the Communist Revolution. He never went back, and he never spoke to us about it until I had the balls—as my mother, who was raised never to ask questions, perceived it—to ask one day. My English grandmother never spoke about the war either, come to think of it. She grew up in Birmingham and the memories of the Blitz were too painful, I was told.

I don’t know much about my Chinese grandmother except that she was born in Burma sometime in the 1920s and was sent to live with family in China when she was six, never to see her parents again—she met my grandfather at the teahouse she worked in and married him when she was seventeen. My hunch is that this is why my dad respected her so much: they were cut from a similar cloth—two figures propelled forward by the geopolitical tempests of history, like colonial shipwrecks cast adrift. Maybe what they felt was similar to the experience of being born in a colony and leaving it when it became part of China. I left the summer of the 1997 handover: the day I entered my new foreign school, Princess Diana died. I haven’t lived in Hong Kong since.

Now that I think about it, I didn’t lose a western reference point so much as a moving one: a person who encapsulated the idea that the self never stops becoming. I’ll admit, this might be why the (Hegelian) dialectic has become such a comfort, somehow, since my father’s death. The dialectic is ultimately about the mediation of binaries—the movement could manifest in a single person or thing, as is the case with the Kinsey scale. The synthesis is the third form: the product of a relation, and we are products of such dynamics—hybrid, contradictory, historical. But we are producers, too; these relations occur constantly, between all things, all the time. You might call it rhizomatic, if not biological—think man plus woman equals baby. In the end, maybe history does become us.

It was years after dad arrived in Hong Kong that the city entered into the postwar boom times. In 1978, Deng Xiaopeng would begin an open door economic policy in China after coming to power. Three major securities exchanges were established in Hong Kong from 1969 onwards, eventually unifying in 1986 with the Association of Stockbrokers in Hong Kong, the first exchange established in 1891. Then, in 1987, the Black Monday economic crash took place. Three years later, he joined the Securities and Futures Commission, an independent regulatory body, when it was established as a direct response to the fallout in 1989, the same year the Tiananmen Square crackdown took place. He became less active on the radio after that; this was a chaotic time world wide, after all.

In Hong Kong alone, Robert Fell writes, the period between 1982 to 1984 saw “a property and stock-market collapse, the murder of a banker, the suicide of a leading lawyer, the flight from the territory of two of his partners and a variety of developers, the defrocking and later imprisonment of the first chairman of the Hong Kong Commodity Exchange, the collapse of banks and indeed the currency, the negotiations with China, a major typhoon, and the visit of Margaret Thatcher to Beijing.” Thatcher’s visits during this period were eventful. She fell down some stairs, triggered a market panic, and signed the joint declaration, in which Hong Kong, a city whose financial markets had been founded on a history of often-aggressive commodities exchanges, was exchanged in a much larger global game.

The handover was dated to June 30 1997. When Tiananmen Square took place five years later, that date felt like a death sentence, even more so when the Basic Law was ratified in 1990 as a guarantee that Hong Kong would be protected for fifty years under international law after 1997. At the time, living in Hong Kong felt like being stuck on the Titanic as the band plays on. Everyone speculated on the risks and considered their own securities and futures. My dad’s indecision as to where to go next became a running joke amongst family and friends, many of whom left before him. Expats, after all, had no idea how secure they would be once the national exchange took place. When it came to the Chinese, the Tiananmen crackdown triggered a fight or flight switch that had brought many to the city in the first place. For others, fear was enough to spark a massive migration wave. Such was the slow unravelling.

Between then and 1997, estimates count between 250,000 to one million people leaving, with a substantial proportion returning in the years after the transition. In 1990 alone, 62,000 emigrated: 1% of Hong Kong’s population. Everyone understood the sense of impermanence and uncertainty; at school, it was common for friends to come and go. Australia, Canada and the US were popular destinations; the UK, too, of course. According to a 1989 poll, about half of all personnel managers, engineers, and bankers said they would “definitely” or “probably” emigrate. Hong Kong’s Madonna, Anita Mui, stated at one point that eighty percent of the entertainment industry were set to leave; Leslie Cheung, Wong Kar Wai’s muse, moved to Canada. The population that remained became politicized, if not watchful.

Yet, as the decade pushed past the economic and political horrors of the late-eighties, Hong Kong flourished, and bubbles—that would eventually burst—expanded. The city was, for a time, a capitalist society Milton Friedman described as “perfect.” I have this one vivid memory from this period in the 90s. It was summer. Dad was sitting at my mother’s dressing table while she was visiting family in Fresno. He was working on a case, with all the lights off save for a tiny desk lamp shooting off a severe beam into the dark. The worst thing about his job, he told me without looking up, was that he knew he was going after people with families—white collar criminals committing intangible crimes. But, as he always said: there are rules to follow. He was making the same face he made whenever he baked pizza from scratch: eyebrows furrowed, his Roman nose pointed at the focus. He was always obsessive about rules, but he was a bit of a gambler, too. I guess that’s why his specialism became insider trading.

That he died months before the 2008 economic crash was fitting: it was the end of an era. When I look back on various cases and statements my father released up until he left the SFC in 2001, he talks about the “integrity of the market.” I wonder what he would say about the integrity of the market now. At his memorial in 2008, we were told that Hong Kong had one of the most transparent markets in the world when dad was working at the SFC—there was a letter in tribute to him from the Securities Exchange Commission in the US. His juniors talked about a man whose eyes made their eyes sharper, and who took a chance on them when no one else would: A kid who left school at sixteen and moved to the other side of the world because he didn’t want to become a British Telecom engineer like his dad. I suppose this is what I miss most about him: he was fearless about doing what he felt was right, though this was a quality I did not appreciate in 1996, when he put two brochures in my hand for two boarding schools in the UK and told me to choose. He didn’t know what was going to happen after the handover. I suppose that’s when the handover became real.

The culture shock was immediate. Within the first months, the girls in my boarding house were taken to dinner at Charlie Chan—Chinese, of course. We had to pre-order food for the one friend we were each allowed to bring. When the food arrived, a dish was placed in front of each person except for my companion and I—we were presented with an array of meat and vegetable plates and two bowls of white rice between us. You might say this was my first concrete experience of cultural difference. Then came the toothpicks.

My parents emigrated to California in 2001, partly because we have Chinese family in Fresno but also, I think, because this is the traditional heartland of amateur radio. Dad brought all his equipment with him, but I don’t think he found much time to use it. He started travelling a lot, too; mostly to see family and friends wherever they were. Perhaps there was a part of him that couldn’t let Hong Kong go. He loved California, though. I could see it when we drove long distances. I think driving gave him the same sense of freedom Ham radio gave him: he could go anywhere, whenever he wanted to—a philosophy he clearly applied to flying towards the end of his life.

He always loved the road. I guess it makes sense he died on it. There’s this photo I love of his car parked on some hilltop road on Hong Kong Island in the late seventies or early 80s, with a clear view of the bay. It makes me think of a black and white photograph of him in England sometime in the 60s, wearing a cowboy hat, a white collared shirt and dark slacks, leaning on a convertible, looking like a teenage Elvis. To this day, I still don’t know where he really came from.

Since my parents left Hong Kong (my mother eventually moved back), the city has weathered the SARS outbreak, the 2008 global economic meltdown that impacted global balances of power, not to mention the influx of a new population as a result of the loosened borders between the city and the mainland, as well as Chinese liquidity and investment. Apartments started reaching sixty floors in vast housing and commercial complexes, not only to accommodate the city’s growing number, but demand in the property market—a new bubble. Old, shitty malls once filled with smoke, pool halls, video arcades, and 7-Elevens became glittering havens for Paul Smith, Gucci, and any other label that never seems to stop trending for ridiculous prices. (One shop manager at a high-end luxury store has stories of accepting cash payments in the millions.) There is a trade in China for goods from Hong Kong, since items here come with a kind of certificate of authenticity in contrast to the shanzhai world of the mainland (just Google “Hong Kong,” “China,” “Milk Powder,” and you’ll get the jist). Then there have been the implications of transitioning over to PRC rule, and the fight for universal suffrage, which was behind the so-called umbrella movement that erupted in 2014. A year earlier, I remember meeting a taxi driver who proudly displayed the old colonial flag as a mark of protest against the current “regime.”

We threw his ashes into the sea. No land for the landless, but water instead—a fluid body for a body that was always moving. He has no grave save for the online memorial Google creates whenever I enter “VS6DO” into the search engine. When the radio community found out about his death, they added “SK” to his sign, as is customary. It means: “silent key.”