I connected the photographs with string and hung them from my office wall. Before me I saw fragments of an entire tradition caught up in something not dissimilar to detective work. But to what end? Had they been working alone? Or had they been hired? Of what infamous plot was I now the latent witness? These photos didn’t seem to reveal anything other than that there was something to be revealed. It was dark outside by the time I left my office that night. As I turned the lights off, I remember hoping that the photographs, hung up as if in a dark room, would somehow un-develop during the night. I returned the next morning to find that they had not. When I glanced over at Brassaï’s fog, I remembered there were still three photographs left to be found and examined. And so Brassaï was to make his second entry.

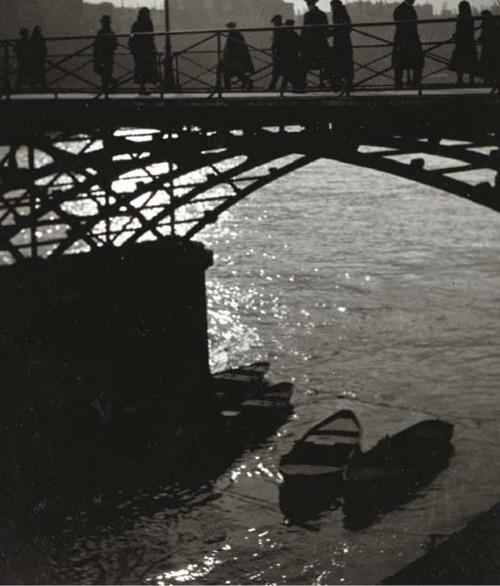

The skyline in the background of this photograph is too nondescript for me to make out what bank of the river they’re on. It is consequently impossible for me to tell whether Brassaï took it in the morning (following a hard night’s graft) or in the evening (marking the beginning of another night shift). I wondered whether those silhouetted figures were going to or returning from work. As I pondered this, I realized that my fixation on the illusive, unseen subject had caused me to overlook an essential tragedy of all these photographs. “I observe with horror an anterior future of which death is the stake,” wrote Roland Barthes. “By giving me the absolute past of the pose, the photograph tells me death in the future.” These baroque specters were walking with the same gait toward an unknown goal. “How alive they are! They have their whole lives before them. But they are also dead.” So many. I had not thought death had undone so many. These darkened silhouettes look like mourners at their own funeral, soon to be absorbed by the black of night.

Was our man among them? I couldn’t say. But I guessed neither could Brassaï. There is nothing to distinguish one figure from the next, so their image could hardly have been of use to anyone. I was drawn instead to the boats on the river, which stand side by side like a pair of shoes – surely an invitation to walk closer. My thoughts turned Robert Capa, another outstanding Hungarian photographer who, like Brassaï before him, worked under a pseudonym and enjoyed a dubious relationship with photographic ethics. As far as I could tell, his role in this case was limited to a piece of advice he offered to fellow photographers: if your pictures aren’t good enough, you’re not close enough. There were two pictures left to examine. Convinced I was closing in on the group, I went back to his biography in search of Capa’s closest friends. Sure enough, Robert Doisneau turned out to have taken a photograph on the Pont des Arts.

Until then, I had not imagined Doisneau would be involved. I have never rated Doisneau, a photographer who as often as not was forced to set a scene up in order to take a good picture. The intention of this photograph is to comment on the fundamental unreliability of painting as an instrument of documentation. Yet Doisneau’s photographic oeuvre inadvertently expresses the same thing in the context of photography, and I wouldn’t be surprised to learn that Doisneau had instructed the artist in this photo to paint the clothed woman as she were nude. Nevertheless, there is often value to be found in Doiseau’s work, though virtually all of it is inadvertent. If you’re going to look at Doisneau, then it’s always a good idea to look away from what Doisneau intends for you to look at.

With this in mind, I cast an eye over to the crouched figure just above the painter’s hat. He is leaning over the rails of the bridge. He is alone. He appears to be waiting for somebody. He is what Barthes would call the punctum of the photo. Readers, the man by the rails is the unseen subject, seen at last. I’m convinced that this man, who has so nimbly avoided the camera until now, has been informed on. I’m also convinced that his informant has been caught on film, too. Walking in the furthermost background, the informer is accompanied by the man who has finally come to catch the face of our true subject on film. But who is this subject of ours? And who are the men approaching? Where is the photograph they’ve come to take?

I knew I was close. The next photo would be the last, after which the case would ostensibly be closed. Yet contrary to how I expected I would behave at this point, I slowed down. I had a feeling the final photograph would ask more questions than it answered; and I knew that once I’d located it, I would have to start telling people about my discovery. The fact is I half-knew who had taken the last photograph. I have spent the best part of my academic life researching the life and work of Henri Cartier-Bresson. It was through my original interest in him that I came to know the works of every photographer I had so far found implicated in this affair. Cartier-Bresson’s collected work is the apogeal document of the entire tradition. There was no doubt in my mind that a figure as central as he was involved in some way – and, moreover, that his involvement would be the culmination of the whole affair.