While France bans face covering, one artist gave fashion ads a hijabizing makeover

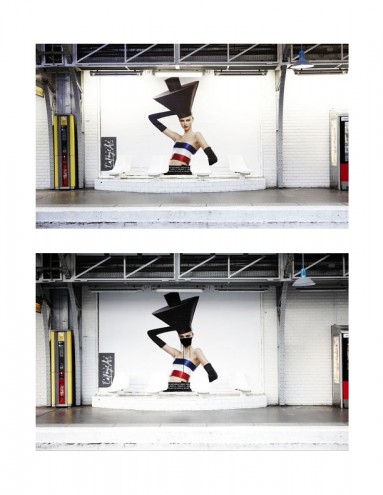

Since France's national ban on face covering went into effect in 2010, the only recorded public assaults in Paris have been made against women wearing niqabs or burqas. This “act prohibiting the concealment of the face in public space” (loi interdisant la dissimulation du visage dans l’espace public) forbids the wearing of veils, masks, balaclavas, and helmets unless they are worn for purposes of “safety” or “entertainment.” Meanwhile, the sphere of fashion suffers no such prohibition: Runway shows and brand campaigns featuring face-covered models are free to proceed, without regulatory interference. Before the ban went into effect—in a sense anticipating it—an anonymous Parisian street artist who goes by Princess Hijab became known for “hijabizing” or blackening the faces of women and men in fashion advertisements. These striking images, in which strategically placed paint partly obscures models’ faces, circulated widely. Princess Hijab ceased the series in 2011, though the technique continues to crop up in the streets.

New Inquiry editor-at-large Maryam Monalisa Gharavi interviews the artist.

MARYAM MONALISA GHARAVI: For years you de-faced and re-faced surfaces, specifically the surface of the face. Why the face?

PRINCESS HIJAB: It was an accidental departure. The way it started was that I didn’t have enough ink available. I realized I’d be more effective in covering only parts of images and that I should be sparing in my gestures. My proclivity is to focus mostly on the face.

The human face does so much social work in public. In a way, it’s the site of an endless performance. Do you see the faces in your images as free from public performance—or free to perform a different kind of performance?

Socially, the face is on permanent display, so for me the masking of it was the real performance. Not showing one part was what changed our shared perception.

In your manifesto, “My Anti Day-Glo Fatwa,” you wrote that you were acting against the visual terrorism of advertising by restoring images to “physical and mental integrity.” I am fascinated by your word choice: “integrity” has multiple etymological and legal connections to “privacy.” If your technique of blackening images restores their bodily integrity or autonomy, does it reflect also on privacy?

I tried to introduce a certain questioning into public space. By working on people’s gaze with the practice of “hijabizing” in the subway, I was “Adbusting,” far from the American references that were predominant in street art at the time. It was a way of reclaiming the self and the space for an (ephemeral) given time.

In one of the earlier ads you—for lack of better words—détourned, defaced, disfigured—there’s something so literal and cliché about the way the Galeries Lafayette department store ad positioned the phrase France as high fashion and high fashion as France. Your defacement makes one turn to the original image again with a kind of renewed wonderment and alarm.

Between the why and the how there are different models of thought. Joining two things which are apparently contradictory can convey a particular strength. That’s what interests me. My approach is openness.

Blackening them out or “hijabizing” them produces a very confrontational effect. The ads are no longer smiling, but glaring. My question is whether we need that effect to achieve confrontation. Is there something specific to face covering that achieves this state of confrontation or horror?

Hijabizing can’t really explain itself very well. It was societal but also energetic and imaginary. This energy which seems to be very direct is linked to the very practice of street art, and I was able to express that through hijabization. There is in each of us something that we wish to exteriorize. You just need the trigger. For my part, the theme of fashion and urbanity was it. Who hasn’t scribbled on a photo by pure reflex?

I have rarely seen race written about in relation to your work. That’s surprising, since nearly all the models are white. You use a black marker to cover up their faces. Were you were wanting to provoke deep, if subconscious, fears of contamination, dirt, and messiness?

The images I used were those that sell advertisements. I can’t help it if as you say they are often white.

France’s niqab ban has been enforced since 2010 but you began imposing face coverings on models in ads well before then. How did the ban change your interventions or how you felt about them?

I began my work well before that event, so they weren’t in fact related. However, I was able to take stock of the fact that my work had become more visible at that moment. It was strongly intensified by the different news events related to the phenomenon of the veil. Sometimes it seemed very funny to me, other times instructive. But it became rather consuming, especially when it was recuperated in an ideological or partisan manner.

Do you mean when others appropriated your images to suite their own agendas or cause?

I mean the dissemination of my work throughout the internet and in certain media has aroused varied reactions, and also some recovery. To limit or orient anyone is not my role.

How much time usually elapsed before the Paris police or an irate member of the public ripped down your work?

Thirty minutes.

The hijabized work you produced was set inside the subways of Paris, not the banlieues. There was little doubt about what audience you anticipated.

I like the language of the city. The language of the subway particularly compels me. There is a multitude of ideas and people there that motivates me. All the riders who pass through the subway come from everywhere, it seems to me, people from the banlieues included. In reality, they are the majority on public transit. I produced my work in public space for those who the city expels as far away as possible, toward the outside, toward the banlieue, beyond the banlieue. They always come back on public transit: Chatelet, Gare Saint-Lazare, Champs Elysée and Gare du Nord.

Has the gothic always been an interest or influence in your work?

Yes, the intrusion of darkness in my work is a recurring attribute.

A few years have passed since your last hijabized work. What made you decide to stop working in that mode?

When I was doing that work it had its scope. Yet I always knew that other experiences were waiting for me afterward, because I was made to keep going in street art.

What work are you focusing on now?

It’s different, but it’s still street art. At the moment I’m working on a collaborative project with the homeless. I’ve gone up from the basements of the city to the surface with the purpose of exploring new territories. Therefore, I’ve chosen to collaborate with homeless people. At some point I conceived and set up a sort of “special fun tool” meant to be freely used by homeless people. Giving the homeless other ways of getting by was our main idea and we achieved it together. This new work is about the imagination and survival strategies linked to the precarity experienced in urban settings. The tool can help homeless people survive and create social connections that they really need, especially these days.

Just as your work endows a highly stylized and specific work with anonymity, you have still managed to preserve your own. It’s not a status many people aspire to, or if they do, feel they can successfully maintain. Beyond the legal concerns—like the necessity of concealing your identity in order to pull off this kind of work—how do you reflect on your anonymity? Can you speak to the power of anonymity, particularly in a society that disfavors it?

I think that anonymity is in itself already a form of expression. There may be some good reasons for wanting to keep it, especially in our era.

Do you still use your fashion disguise of a hoodie and a long black wig? Or do you no longer obscure your face?

I want to clarify that it was my real hair that I had sewn into the cloth. That was an integral part of my identity. The hair in my face was a bit shamanic. In fact it added more constraints. I saw poorly and I had to always guess at shapes to be able to work. That asked a lot of the other senses, like hearing and touch. Despite these difficulties, I always maintain this approach to the transformation of my appearance!

If I have to use a gender to refer to you I always choose gender-neutral or use a hyphen—her/him, she/he. Yet the Princess Hijab persona is female and that isn’t unimportant in the world of street art largely dominated by men, or the world of your themes. How important is a gender characterization to you?

I am a fiction in all of this.