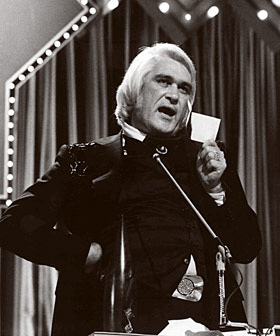

Charlie Rich stands on the stage of the Grand Ole Opry House in Nashville. In his hand, he holds an envelope containing the name of the winner of the 1975 Country Music Association Award for Entertainer of the Year. (Rich himself received this recognition the year before.) As he begins to speak—“haltingly,” the Los Angeles Times will describe it later—he drops the envelope to the floor. Having retrieved it, he holds it up for all to see. Then, without a word, he takes out his cigarette lighter and sets the card on fire. “The award goes,” he announces as flames consume the envelope, “to my good friend John Denver.”

[l]Charlie Rich at the 1975 CMAs[/l]

[l]Charlie Rich at the 1975 CMAs[/l]

What just happened? As in Hawthorne’s Scarlet Letter, when the townsfolk will forever dispute the meaning of Dimmesdale’s revelations on the scaffold, the matter remains contested. If you ask Rich’s son, who administers a website devoted to his father’s memory, it was an unfortunate accident: Rich had reacted poorly to (legitimately prescribed!) medication. But for nearly everyone else, another interpretation of the stunt has proved irresistible. In their view, Rich was protesting the encroachment of lightweight pop-country into the Opry, a hallowed venue whose continuous country radio broadcasts since 1925 made it almost as old the genre itself. I would go one step further. Rich’s rebellion at the 1975 Country Music Awards was an act of radical working class self-assurance, best understood in the context of the forgotten labor history of the 1970s.

Despite caricatures of a navel-gazing “Me Decade” which saw American workers smoothly integrated into a totally administered society, the 1970s were marked by levels of labor militancy that rivaled the Great Depression and the tumultuous periods after both world wars. Strikers set single-year records for records for work stoppages, authorized or not. The liberal consensus established by the 1960s—Keynesian economic management, high union density, and near full employment—gave workers an unusual willingness to resist their bosses (and sometimes their union leaders) at the points of production. As economist Michal Kalecki

had predicted decades earlier in “Political Aspects of Full Employment,” tight labor markets meant that “the social position of the boss would be undermined, and the selfassurance and class-consciousness of the working class would grow.”

“The class war in the long 1970s,” writes historian Aaron Brenner, provoked “military intervention on several occasions...dozens of anti-labor injunctions, hundreds of arrests [and] numerous calls for anti-strike legislation.” Charlie Rich, for his part, was not invited back to the CMA Awards, and never received another nomination from the organization. The culture industry interpreted the envelope burning as a cry of “take this job and shove it.” Rich’s onstage protest was the equivalent of individual industrial sabotage. But rank-and-file resistance to the CMA produced something less ephemeral, if less remembered, than this flaming fuck-you. In 1974, the same year the United Mine Workers of America struck to win the best contract in their history and the socialist president of AFSCME told striking municipal workers to “let Baltimore burn,” the Association of Country Entertainers organized to protest the CMA. The industry’s offense: passing over nominees like Loretta Lynn and Dolly Parton to name Olivia Newton-John Best Female Vocalist.

Newton-John was a controversial choice, not only because, like Denver, she played a watered-down pop style of country. She was a literal and figurative foreigner, born in Britain, raised in Australia, and painfully unversed in the lore of country music. Upon coming to America, the story goes, she said she wanted to meet Hank Williams, whose death had legendarily taken place on New Year’s Day, 1953. More crucially, NewtonJohn refrained from publicly identifying herself as a country singer. This was too much. After the 1974 awards ceremony, a midnight meeting was held at the house of country singers George Jones and Tammy Wynette. The result was the ACE. The ACE would be different from the CMA in only enrolling those who made their living as singers and musicians. Limiting membership to the rank and file would exclude the moneychangers and middlemen whose votes the artists blamed for the Newton-John embarrassment. (Only 2 of 30 members of the CMA board at the time were entertainers, and none of its 13 officers.)

Labor militants in the 1970s were notable for transcending bread-and-butter economic issues to raise matters of workplace control and quality of life. Exemplary of this trend were the series of strikes, both wildcat and official, which rocked GM’s Lordstown complex between 1972 and 1974. At Lordstown, workers were forced to assemble more than 100 cars an hour. The strikers (some of whom, the media loved to point out, looked like hippies) “voiced hatred of the assembly line itself and questioned the necessity of the capitalist division of work.” Though Lordstown became the most famous case, similar demands for autonomous and meaningful work were voiced in many industries.

There is something of this spirit in the ACE, whose star-studded membership—including Johnny Cash, Conway Twitty, and Roy Acuff—wasn’t exactly concerned with wages and hours. (Musicians’ unions already existed to deal with those issues.) The dissident country singers were staking a claim to control the conditions of the industry they worked in, and demanding dignity commensurate to their crucial role in the production process. The CMA, after all, originated as a management strategy to transform country music—and its audience—into commodities attractive to advertisers. In the 1960s, historian Diane Pecknold writes in The Selling Sound: The Rise of the Country Music Industry, an increasingly well-organized Nashville establishment sought to “revise popular understandings of the Southern migrant and the working class” and the country music they loved. A country awards show akin to the Oscars and Grammys were part of this “cultural redemption of the country audience”—in other words, a standardization of that audience which effaced integral regional and cultural differences.

“We are the vehicle of country music,” said ACE member Billy Walker. “We have to have a place for our voice to be heard.” According to a statement issued by 50 founding members, the ACE’s “primary purpose will be to preserve the identity of country music as a separate and distinct form of entertainment.” Speaking more bluntly, chairman Bill Anderson told the press “Our gripe, if we have one, is that these people want to come in and take our music away.”

The formation of the ACE was a daring attempt to take on the “big money [that] prostituted our business”, but the organization’s existence was brief and troubled. Although they publicly disclaimed hostility to the CMA, the dissidents were perceived by management as recalcitrant workers and dealt with accordingly. Billboard, in ostensibly “journalistic” coverage, accused ACE members of hypocrisy for not having been active enough in the CMA or for being unsupportably poppy themselves. ( Jones and Wynette made albums with strings-addicted countrypolitan producer Billie Sherrill, as did Charlie Rich.) Such vague but ominous pressure from an industry organ constituted the rough equivalent of a capital strike. Famous artists backed out and later played down their initial involvement. The CMA also made an effort to contain dissidence by diversifying its board to include more performers. By the mid-1980s the perpetually underfunded organization shut its doors.

***

By stressing the historical simultaneity of the ACE and the rank-and-file revolt of the 1970s, I don’t mean to suggest the country stars explicitly understood their struggle as labor activism. But if we can still believe in such a thing as the zeitgeist, it is clear that the two phenomena were different manifestations of the same impulse. Both stories, lost to historical amnesia, seem completely foreign today, examples of faded defiance among so-called middle Americans. Each narrative also belie liberal perceptions of country music and the white working class as incorrigibly conservative. (One need only look at the New York Times’s man-bites-dog shock at encountering “irate longhairs, not on college campuses, but among blue collar workers” to see what I mean.) Through ignorance of working class culture, and outright snobbery, many upper-middle class Americans understand blue collar and red flag as mutually exclusive loyalties. The hollowness of this judgment is shown by the history of working class struggles in the 1970s.

These twin tales, it must be admitted, form a dialectic of defeat. The ACE was a failure, and unions have never recovered from the neoliberal counteroffensive already underway by the late 1970s. In 1986, around the time the ACE met its demise, the Lordstown factory celebrated its 20th anniversary. Against a backdrop of plant closings and layoffs, chastened labor leaders joined management to “celebrate years of relative peace, saying the strikes of the ‘70s are a thing of the past.” But Alan Jackson and George Strait’s awards-show performance of “Murder on Music Row,” which charges “the almighty dollar” with the “kill[ing] country music,” shows that televised industry galas remain an active terrain of conflict. And Great Recession-era actions—a three-day strike at Lordstown in 2007, the recent Chicago teachers’ strike, and especially the Republic Windows and Doors sit-down strike—though pale by comparison to the wild 1970s, at least suggest that failure doesn’t have to be forever.