When focusing on symptoms of austerity, media transfers blame to CUNY student body

This is the oppressor’s language

yet I need it to talk to you—Adrienne Rich, “The Burning of

Paper Instead of Children” (1971)

THE City University of New York (CUNY), the country’s largest urban university system, is broken. As both a graduate student and an instructor at CUNY, I find my inbox flooded with emails about the institution’s ongoing financial crisis: library hours are now limited, escalators can only function as stairs, our union is moving to strike.

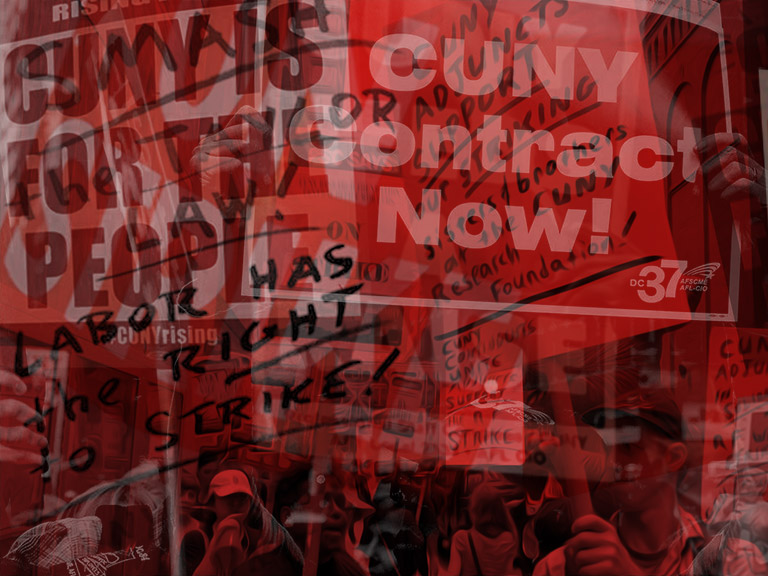

The severity of CUNY’s crisis led the institution’s labor union, the Professional Staff Congress (PSC-CUNY), to vote this May to approve an impending strike, with 92 percent support from students, faculty, and staff represented by the union. In August, staff and administrators ratified a contract that potentially resolves the long-standing lack of benefits for workers. Independent media outlets covering the crisis use CUNY, and its history of labor organizing, as a model of mobilization. Successful organizing at CUNY is taken to represent victory for public students and adjunct workers everywhere.

The official approval of the PSC contract, however, was not without widespread dissent from graduate student workers and adjunct instructors, who maintain that it does little to rectify their working conditions, the result of extreme divestment from public education that borders on neglect -- in a word, austerity.

This past June, in the essay “Degrees of Austerity” in Jacobin, Brooklyn College professor Corey Robin highlighted the urgency of these conditions as evident in the deterioration of the institution’s 24 campuses. The article portrays CUNY facilities, especially at Brooklyn College, as shabby and derelict, noting “leaky ceilings, clogged toilets, stagnant salaries, and ballooning class sizes.” Floppy disks made an appearance.

This depiction of CUNY as literally crumbling succeeds in drawing attention to the situation. But, in accentuating the symptoms of crisis, it risks transferring the shortcomings of a dysfunctional system onto the 274,000 students who work to study within it.

Mainstream media accounts of CUNY’s crisis consistently struggle to respectfully represent the school’s students. Urgent narratives of destitution are coupled with stories of aspiration. A recent New York Times article, “Dreams Stall as CUNY, New York City’s Engine of Mobility, Sputters,” characterizes CUNY students as “ambitious children of families from around the world, many of them poor and working class.” This and similar articles cast students as either desperate paupers or dignified hustlers, collectively described as “New York’s striving class.”

For better or worse, CUNY students are widely perceived as impoverished. “The biggest problem City College has faced over the years is the shame that goes with poverty,” writes professor of music Stephen Jablonsky, who has taught at City College of New York, since 1964. Not poverty itself, but the knowledge of how poverty is perceived by the public -- a process of distortion by which students find their conditions of existence stigmatized, but rarely historicized.

Such depictions may spread awareness of marginalization at CUNY campuses, but they conceal contexts of social stratification and student struggle. Their myopic focus -- on institutional failings and student striving -- risks naturalizing austerity policies.

A few years ago, when an Ivy League graduate discovered I was a student at CUNY’s Graduate Center, he teased me about the school’s legacy of disenfranchisement. “You like being oppressed,” he said with a chuckle. He was likely suggesting we public university students enjoy our marginalized status, not for power or respect—we don’t have much, as he saw it—but for the granule of authenticity the institution’s history of struggle grants us.

It is easy to portray CUNY students as striving. Coverage of the current crisis relies on statistics intended to prompt pity for the “disadvantaged” student body: more than half of students’ family incomes are less than $30,000 a year; 42 percent of students are the first in their family to attend college; 75 percent are students of color. Half of all students at CUNY’s senior colleges work for pay in addition to attending school, according to data from 2014, and of those working students, 31 percent work more than 35 hours per week. Among students who don’t work, 50 percent said they need to work but are unable to find employment.

But statistics only go so far. Sofia Samatar explores the limits of quantitative representation in her essay “Skin Feeling,” in which she writes: “In the logic of diversity work, bodies of color form a material that must accumulate until it reaches a certain mass.” As she suggests, diversity itself can perhaps be represented through statistics, but the vital work of anti-racism evades such reduction. Similarly, although data about CUNY’s students may satisfy our desire to represent their poverty, statistics about “working class students” tell us little about the nature and content of students’ actual work.

This disparity between lived reality and its representation inspired the “crisis of representation” that spread throughout humanities scholarship in the 1980s, when scholars grew concerned with the depiction of people in news and art. As early as 1926, The Crisis -- the journal for the NAACP -- engaged this issue, publishing a symposium called “The Negro in Art: How Shall He Be Portrayed.” It opened with a series of questions such as, “Can any author be criticized for painting the worst or the best characters of a group?” Today, CUNY finds itself in this dilemma.

Fetishization of the disenfranchisement of students, which reduces them to a marginalized mass, in turn generates narratives of aspiration. “Don’t Dilute CUNY’s Urban Mission,” reads the headline of a Times editorial, describing the school’s “historic commitment to the urban poor” and its “aims to develop upwardly mobile students.” The editorial is right to call for increased funding to CUNY’s campuses, but its logic is misguided: in concluding that austerity threatens “the special character of the city system,” the authors imply that this “special character” -- meaning marginalization and struggle -- is one worth preserving, rather than deconstructing with care.

The paradox of narratives of ambition is that they require the maintenance of a marginalized position from which subjects can rise. CUNY’s internal promotional campaigns are thus torn between superficially elevating the institution and making it seem accessible. Branding strategies for City College, one of the oldest CUNY campuses, capture the tension at play: the school has long been termed “the Harvard on the Hudson,” an attempt to praise City College that functions as product placement for the school’s Ivy League neighbor. The phrase elevates the Ivy Leagues and casts CUNY and its students as inadequate by comparison.

This internalized hierarchy floats up into mainstream reporting -- as recently as May, the New York Times called the school the “poor man’s Harvard.” This reputation of CUNY as a cheap alternative to private universities has drawn objection from Barbara Bowen, president of the PSC. “It’s making CUNY the Wal-Mart of education,” she said last year. The ongoing, uncritical repetition of these clichés advances a demand for upward mobility that is largely unrealizable in our economy; media accounts tend to reiterate this demand for growth rather than explore the financial conditions that make the demand unreasonable.

IN succumbing to the hierarchical logic of privilege and aspiration, public institutions are forced to mimic the principles of corporations, even as these principles consistently fail to serve public interests. In a bout of neoliberal marketing, CUNY’s own website notes that the employment needs of companies should “shape the direction of curricular innovation” at the CUNY campuses. Doctoral candidate Kristofer Petersen-Overton critiqued this problematic leadership ethos as “a boardroom mentality in university administrations.” This mindset produces an environment in which, in Corey Robin’s words, “educators talk like accountants.”

Under pressure to add value to CUNY’s brand, hiring committees are compelled to prioritize personality at the cost of actual departmental needs. In 2014, after celeb-economist Paul Krugman was appointed to the CUNY Graduate Center faculty, graduate student Sean M. Kennedy argued,

The terms of Krugman’s hire represent a fundamental contradiction in the hegemony of the “lack of money” that rules the practices and discussions of public higher education. Indeed, there is always money to be had … CUNY is desperate for world-class status, even if it means running its students, faculty, and staff into the ground.

Media representations of CUNY as a venue of upward mobility for disenfranchised students take for granted principles of corporate economics such as privatization, profit, and infinite growth. Meanwhile, these same principles underlie the austerity measures within public higher education that make meaningful work -- that which can’t be represented by a number -- feel impossible for CUNY students.

FOR as long as public university students have been represented, they have explored the hypocrisies embedded within representation itself. In a recent statement, Students for Educational Rights (SER), a student organization founded in 1989 at City College, writes, “We stand in a long tradition of activism at CUNY, where the case has always been that if something is wrong students stand up and change it.”

In Fall 2015, SER organized a protest at City College against tuition increases, cuts to course offerings, and precarious employment for adjunct instructors. At the event, music was provided by a free jazz duet, featuring two music students expansively riffing on a Coltrane tune. (There’s a long tradition of jazz history at the school; Ron Carter, bass player on Miles Davis’s album Miles Smiles, taught in the music department for 20 years.) It’s this kind of innovative response to injustice that is characteristic of CUNY’s history.

SER welcomes coverage of financial struggles at CUNY, insofar as this attention helps to pressure the state, “particularly Governor Cuomo,” to adequately fund the school. CUNY is funded by a combination of city and state money, the latter of which Governor Andrew Cuomo threatened in March 2016 to cut by $485 million annually. Cuomo’s office, when accused of failing public university students, shifted blame to CUNY Chancellor James Milliken, whose salary last year was $490,567.

At the municipal level, New York City’s projected budget for fiscal years 2016 to 2018 involves a 7 percent decrease in funding to CUNY -- and although funding for the fire department, social services, and sanitation all face similar cuts, funding for the NYPD is set to increase by $2 million by 2018.

As New York cultural critic Ellen Willis put it in her essay “Intellectual Work in the Culture of Austerity” (2000), such constrictions within higher education often feel like those of a zoo -- to which “the hounds growl that, in an age of austerity, a cage should be enough.”

These constraints have a long history, as does resistance to them. Poet Adrienne Rich, who taught at City College in the 1960s, noted her students’ struggles amid low budgets. In her 1972 essay documenting those years, “Teaching Language in Open Admissions,” she recalled students who felt the “incessant pressure of time and money driving at them to rush, to get through, to amass the needed credits somehow, to drop out, to stay on with gritted teeth.” If Rich was correct in her melancholy assessment of students’ experiences then, she reminds us that current pressures in higher education are not new.

Rich taught in the Search for Education, Elevation, and Knowledge program (SEEK), which was founded at City College in 1965 before extending to the other senior colleges in 1967. The program was inspired by, and inspired, activities at other public colleges such as San Francisco State, where the country’s first Black studies programs developed. The intention of SEEK was, and still is, to counteract inequalities of class and race built into higher education.

In 1965, CUNY implemented policies of open admissions and free tuition, which made CUNY more accessible to “underprepared” students via remedial coursework. These policies, which ended in the mid-1970s, were seen by many New Yorkers as the beginning of the institution’s decline in quality. During that time, as a city government report notes, “The racial integration of the senior [CUNY] colleges became inextricably linked with the admission of severely underprepared students to those colleges,” a connection by which the expanded inclusion of students of color in CUNY’s system was used as a scapegoat for deeper systemic problems.

An important project of SEEK was to counteract such erasures within higher education. The program’s students critiqued Eurocentric canons and helped create syllabi that were more reflective of the lived realities of CUNY students, who come from 204 different countries. Program leaders like Rich used poetry to grapple with the necessity of representing oneself within an inherited, oppressive system. She writes in her poem “Tear Gas” (1969):

I need a language to hear myself with

to see myself in

a language like pigment released on the board

blood-black, sexual green, reds

veined with contradictions.

AFTER I started teaching as a graduate student, one of my former professors recommended I read Centering by M. C. Richards, a Black Mountain College poet who taught at City College in the 1960s. In the book, Richards describes what she learned from students in the class she taught there: “They are patient with my obtuseness, they check my too quick judgments.”

Media rushes to represent the CUNY community as we mobilize for better working conditions. In doing so, this coverage routinely takes for granted inherited conventions of representation rather than challenging them. We do need media coverage to help us resist austerity, but we don’t