(via John Foster)

On sense and subjectivity in the poetry of Dan Beachy-Quick

We fear that we can’t communicate our thoughts or experience to others. When we do speak or write we fear that our words are restricted to a socially-prescribed script, that we have nothing interesting or new to say.

This is the challenge—and the attraction—of reading the poetry of Dan Beachy-Quick, whose work acknowledges and attempts to offer solutions to these very anxieties.

I.

In Spell, a book-length response to Moby Dick, a poet desperately writes his editor.

Sir, my hopes lay in your printing press—

Forgive me what I write to you,

I promised my loose-leafed work a center

Of glue. I’m sorry—I’ve none to ask—but you.

A literal reading of Spell would lead one to believe that Beachy-Quick is concerned with saying something new about Moby Dick, but the book’s value lies in the way it shows us what it feels like to attempt to do so—a far more impressive achievement.

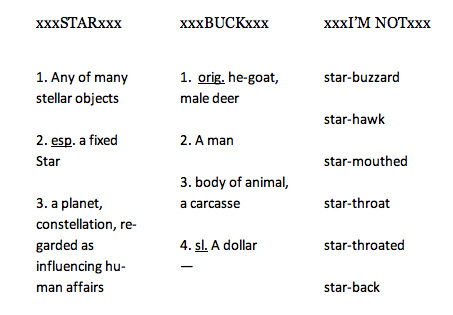

This is captured not only through explicit statements in the poet’s letters to the editor, but also through poems that intentionally fall short of their goal.Spell’s poems contain fragmentary ideas. They alternate between stark, rigid columns and airy pieces with sprawling indentations. They convey the sense that we’re seeing a work in progress, and that we are privy to the false-starts, and chaotic attempts to unify disparate ideas that are inherent in writing, as well as the emotional impact that that process has on the poet. Here the poet-protagonist organizes his ideas on the character Starbuck.

Beachy-Quick chooses to sidestep the question of whether the poet actually says something original about Moby Dick. One could imagine the book concluding with the final versions of the poems that we watched the poet draft. Instead we are told that the poet has mailed the completed poems to his editor, but in the final chapter of poems in progress, the alphabetically-sequenced poems break precedent and skip the letter “D”. Whatever the poet says about Moby Dickis ultimately not for us to see. By leaving out the finished poems, Beachy-Quick indicates to us that the meat of the book is the examination of whether that project is possible at all.

II.

And is it? Rather than answer that question in isolation Beachy-Quick builds it into the one that logically follows: can we ever be sure that what we say will be understood? This question is true in everyday experience but if irresolvable is especially crippling to a writer, whose primary tools, language and experience, are also his primary obstacles to overcome.

The poet’s tool is language, which conjures images and colors them with tonality. Yet, in some of the most rewarding passages in Spell and in various moments throughout all of his other major works, Beachy-Quick shows that these means of communication are flawed pathways to mutual understanding. Words may relate to their referents by virtue of common agreement, but even so they connote and denote different things to each of us, depending on our particular experience and background. Experience, which Beachy-Quick confronts primarily through sight and sound (the senses most relevant to the art of poetry), is perceived via temporally removed and scattered photons that enter the eye of only one person at a time rendering sight effectively subjective. The experience of sound is equally indirect as it is sensed by casting waves through space from an object into the ear. Sound is a subservient sense to sight, as sounds serve as stand-ins for visual stimuli.

Beachy-Quick’s examination of the limitations of language, of sight and sound as means of communication are most prominent in This Nest, SwiftPasserine. The collection is densely populated with italicized excerpts from sources as varied as Dorothy Wordsworth, Empedocles, Martin Buber, Simone Weil, Heidegger, and the Bible. Here he speaks to the problem of communicating experience in a passage interwoven with excerpts from Milton’s letter to Leonard Philarus.

my eyes both night and day

and my comfort if comfort it was

I saw in the pages that closing

narrowed the whole day into a minute

quantity of light as if through a crack

and I had no way to speak of it

and then it was done

In addition to the writings of poets and philosophers, Beachy-Quick populates his books with dozens of intentionally-chosen bird species. By my count, Mulberry names birds in more than twenty-eight instances across eighteen species, in addition to references to nests, migration, and quills. To an avid birdwatcher like Beachy-Quick, those birds communicate a range of meanings as loaded as the literary references do to those who are familiar their work. For example, if you know that the eponymous passerines an order of birds commonly referred to as “songbirds,” you’re cued to read the poems with attention to sound.

It is through this hyper-attention to minutiae that we see Beachy-Quick start to offer and apply his solution to the difficulties of communicating experience. By drawing from a plurality of imagery, schools of thought, and literary sources, Beachy-Quick argues that any quest for understanding ought to be open to multiple fields of knowledge. The encyclopedia is truer than any one of its entries. The best way to ensure that we are understood is to avoid isolating our ideas. Cross-referencing, whether in poetry or everyday speech, means that even if we are not understood directly, we give more opportunities for our audience to home in on our meaning.

This obsessive linking is present throughout his body of work, but it is done most dramatically in A Whaler’s Dictionary: the imagined, meditative reference work of Ishmael’s ambition. Every alphabetized essay-poem within is cross-referenced (except for one, which you must happen upon) and the reader is encouraged to follow her own whims by turning to an entry of interest and then jumping to the next by referring to a chapter called “see also” at the end.

III.

Perhaps satisfied that he has resolved the problems of originality and communication, Beachy-Quick’s latest chapbook, Heroisms marks a shift from a concern with subjective to intersubjective knowledge. Beachy-Quick has set aside the anxiety of being heard and has returned to addressing one of the concerns of Spell: the anxiety of worthiness.

But there is a shift between the two poems. In Spell the worry was having something worth saying; in Heroisms, it is embodying a self worthy of praise. We are presented with a pathetic protagonist referred to only as “the hero,”

His penis grown so long he loops it through

His belt-loops to keep his pants up

And still its tip drags in the dust behind him

Drawing a line pointing backward

To everything the hero’s entered.

How the nameless “hero” has earned such an accolade is unknown to us and weighs uneasily on him. Praise of the hero originates in human hands clapping and is echoed in the clapping-together of hand-like leaves in the wind. But the hero is unsuccessful in embodying this adulation. Human words fall from his mouth artificially, as if he were a ventriloquist’s dummy. That the poet is also a kind of ventriloquist has been touched upon in Beachy-Quick’s previous works, but it isn’t until Heroisms that we see an in-depth exploration of the problem of separating one’s own voice from that of others or of society. Now we see the ventriloquist from the other side, from the perspective of the one being spoken through.

The poem follows the hero’s attempts to internalize the identity placed upon him. The natural world, which becomes transcendentally conflated with human society, applauds with leaves and issues judgments with flowers’ eyes. At one point the hero makes a literal attempt to internalize the praise by swallowing seeds, which causes his “his intestines [to] consider gardens.” But it doesn’t take. After 25 poems, Beachy-Quick’s hero definitively renounces his title and “runs/Away from his own applause.”

IV.

In the end, I don’t think Beachy-Quick has the definitive solution to any of his three primary questions. But he brings a unique voice to a centuries-long conversation. His method of interdisciplinary cataloguing is as absorbing as it is necessary. He brings together the history of thought and knowledge that he has inherited and takes the discourse a step further while showing enough humanity to acknowledge that the weight and potential for failure of the project bring him great anxiety. Watching Beachy-Quick explore these themes, we become better equipped to make contributions of our own. When the poet communicates to his reader, it seems as if, for a moment, it is possible for us all.