All the photographs that will ever exist of Harriet Tubman already exist. This is the postmortem arithmetic that governs evidence of a life already lived: some photographs may be lost, but no more will ever be taken. Nevertheless, newspapers in March 2017 reported the discovery of a new photograph of Tubman, posed for sometime between 1866 and 1868. Of course, the photograph is not new—it was not even unknown, but it is newly available to collective knowledge.

Tina M. Campt,

Listening to Images,

Duke University Press Books,

2017, 152 pages.

The photograph itself is not spectacular. It does not alter our view of Harriet Tubman, except maybe in showing that she was once a younger woman than we imagine her to be. USA Today described the photo in tabloid terms: “Harriet Tubman has a new look…slim, impeccably dressed and confident.” It is a studio portrait, a carte de visite given to abolitionist Emily Howland as a memento between friends. It expands the collection of photographs of Harriet Tubman, of Black woman abolitionists even, known to exist by the broad public by a large percentage point. It is an exciting discovery in the sense that it seems to defeat time.

In Listening to Images, a slim new volume from Duke Press, Tina Campt, a professor of Africana and gender studies, engages diverse archives of what she describes as “quiet and quotidian” photos from the Black diaspora, like Tubman’s, toward a project of Black futurity. Western modernity has always been a project built on anti-Blackness through colonialism and the Atlantic slave trade—Black lives have always been under threat in this context. Our present is the afterlife of these foundational violences.

Campt has written extensively about photographs from the Black diaspora, in an earlier book, Image Matters: Archive, Photography, and the African Diaspora in Europe. Her work is particularly noteworthy for her ability to translate still images into moving narratives, to carry the reader through the image. Campt’s archive for Listening to Images is made of photos that one might pass over when looking for a more spectacular story. These include modes of identification photography—mugshots, passport photos—that reveal the apparatus of state control without its spectacular action or violence. These images are the low-tech precursor to the current proliferation of biometrics, the practice of tracking unique identity markers like DNA. Campt’s turn away from crisis brings the spectacle into perspective. She attends to the long backdrop of the eruptions of supposedly exceptional violence that is far too often overlooked, but is always present.

Campt analyzes photographs that seem to show nothing at all, like a still portrait of an unmoving face. For her, these index both normalized social relations of abjection and terror for Black people, and their unthinkable, enduring capacity of living in spite of these relations. Following the foundational theorizing of Hortense Spillers and its extension by Alexander Weheliye on the flesh as that which prefigures the (human) body—exclusion from the status of human, figured through the category of whiteness, does not necessarily connote death. One can live within the flesh as a non-white mode of being. From ethnographic portraits of indigenous African women, and missionary portraits with their investment in Black respectability, to carceral mugshots and even passport photos, Campt reads the archive against itself, tracking refusal and self-fashioning in the identification photographs that are meant to categorize or restrict.

Campt approaches Listening to Images’ wide-ranging archive via a counter-intuitive and at times exasperating method signaled by the book’s title: how can you listen to images? Following the foundational writings of cultural studies scholar Paul Gilroy on the sounds of the Black Atlantic, Campt theorizes “sound as an inherently embodied process that registers at multiple levels of the human sensorium.” She cites, for example, the experience of sound that does not require hearing, the ways that humans feel sound in the body. For Gilroy in The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness, the power of Black music as an ethical value is in its “obstinate and consistent commitment to the idea of a better future,” a “politics of transfiguration” which necessarily “exists on a lower frequency” in the music, out of the range of hearing of overseers and other oppressors. This is the inaudible frequency Campt tunes herself to and works to hear across faculties of perception.

“Listening” for Campt is not the same as hearing, and operates in multiple directions. First, as a way of denoting affective and haptic encounters with photographs—the sense that one might experience frequencies or vibrations between the self and the photograph. Campt invites the viewer to listen to the hum, the low frequency that is felt rather than heard, in order to connect the viewer to the event that the photograph may only connote. The photograph becomes an actor in the encounter, one of multiple conative bodies in space that interact and touch each other. This requires an act of imagination perhaps, but so does building the world we want to see; so does actively creating a future in which Black people can thrive. When dominant structures of apperception in the afterlife of colonialism and chattel slavery reproduce anti-Blackness, transformations toward utopian desire require a broadening of one’s tools—a turn to other senses, other ways of perceiving.

Imagine each photograph as a still shot which one could zoom into and open a frame full of motion and sound. The portrait-sitter is still, but only for a moment frozen in time. Listening as an act attached to a portrait connotes dual action—one listens and the other speaks—which restores temporality (and therefore, humanity) to that which is plucked from time or trapped in the past, prevented from forward motion.

Campt extends her initial interest in identification photography in uneasy directions: ethnographic photography, studio portraits of Christian African families, a picture in the newspaper that once gripped her. She asks the reader to travel with her across borders of space and time under the assumption of an ideological scaffolding that persists. The white look, as Frantz Fanon named it, is one that fixes Blackness as abject through the history of the image, but the Black look gazes back, meets the eyes and looks past them and into the future. Campt’s demand is directed to the reader: across time and space, you are the one who is looking now. What histories structure your gaze? What will you do with your look?

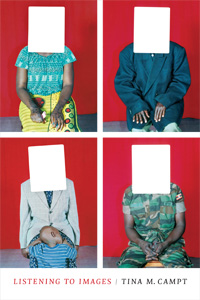

A collection of discarded studio portraits from Gulu, Uganda, the faces surreally cut out for the startlingly mundane usage as identification photographs, becomes a story about the agential desire for neoliberal access in the face of war and displacement. The need for identification by the portrait-sitters to move through the world, to access jobs and aid, produced strange art—the serial portrait without a face. Each photograph repeats the same scene with a difference, the colorful clothing, the repetition of a suit jacket provided by the photo studio and the same red backdrop, the many hands clasped on laps. The full-body studio portrait is a byproduct of the head shot required for identification cards, and so they are discarded, each missing its face, as if they have been censored.

The stylistic repetition of the identification photograph grips Campt; she heeds the call to lean in, to ask more of the discarded image. Attending to this desire to know is a strength of Campt’s text: the collections she narrates, the way she places herself as a researcher discovering these images, in galleries, in archives, through coincidence or design. At the same time, the stories diverge; the faces cut out of the Gulu studio portraits become ID cards, attached to a name, citizenship, a life. The discarded frames become another story about neoliberal access, one that Campt sets aside. The encounter between the photograph and the author is enabled via the fine art economy, mediated by a curator. They are gathered by a white Italian photojournalist, exhibited under her name as found art at a gallery in New York, where they are encountered by Campt as quiet images in a quiet space. The vernacular is noisy, but photographs removed from the everyday are quiet in quiet spaces.

Listening to Images reads as an opening, a methodological invocation, an attempt to harness synesthesia in the service of survival. Because of this, listening at times seems vestibulary: an entry point but not the point itself. The book gestures at but does not really engage with sound studies as a discipline, either in citation or in aural analysis. In this sense, Campt’s project fits better in a landscape of visual studies scholarship which, following the work of Fanon, Sylvia Wynter, Christina Sharpe and Shawn Michelle Smith, among others, traces an exclusionary Western project of defining the human through the visual by skin color. If the present moment is a continuation of a regime in which Blackness is antithetical to humanness, and the eye is the purveyor of that truth, then we must learn to look differently. Look at these quiet images and hear the grammar of Black life, in the tradition of Hortense Spillers. As Campt evocatively writes of the “future real conditional or that which will have had to happen […] the grammar of black feminist futurity is a performance of a future that hasn’t happened but must.”

Through the logic of Campt’s reading, the newly discovered portrait of Tubman, with her name signed in script across the bottom of her skirt, is an invocation from the past of the future real conditional. The Civil War has just ended, slavery is over—it is an incredible moment of hope and possibility. Tubman has been a slave, a fugitive, a soldier, and a spy. She has led an armed raid that rescued over 750 enslaved people and has personally escorted over 300 others to the North on the Underground Railroad. She has given much of her life to that which will have had to happen—to Black feminist futurity against total dehumanization.

Here is the cognitive effect of the translation of image into words, the pairing of a photograph and the index: “Harriet Tubman, abolitionist.” Listening to Images in many ways ends up being a wide-ranging argument for inquisitive viewing, for looking at a photograph and placing it in a narrative, for encountering photographs in space and experiencing them fully as embodied subjects. This level of engagement with the image and the event restores in viewing practice a level of complexity often denied to Black lives. “Who is gazing?” Campt cites the question posed by South African photographer Santi Mofokeng in his project “The Black Photo Album/ Look At Me: 1890–1950.” The photograph or archive of photographs—even, or especially, those which seem to show nothing at all—is transformed into meaning by the eyes and the gut of the viewer.

Campt concludes her productively uneasy assemblage of archives with a contemporary and digital collection—pictures curated from the hashtag #IfTheyGunnedMeDown, the social media response to the media representation of Michael Brown after he was murdered by police. The hashtag, with the implied and stated question “Which picture would they use?” critiqued the stereotypical representation of Black teens as aggressors and threats after their deaths by state violence, a particular strain of racist victim-blaming. In the face of actual mortality, the hashtag project invokes a complexity that transcends respectability politics—Harriet Tubman destroying and stealing private property on the Combahee River Raid, getting crunk at the afterparty, and sitting pretty in a Quaker abolitionist’s parlor. A Black teenage boy grimacing with a grill, as well as in graduation robes. It’s the Black future real conditional “get you someone who can do both.”

Campt reads these images in the tradition of self-fashioning of all the quiet images before—the tension in the jaw of the coiffed woman in the ethnographic portrait, the blurred line of fugitivity and citizenship in a passport photo of a handsome man in a suit taken in a poor immigrant neighborhood and red light district. The paired portraits in the archive of #IfTheyGunnedMeDown represent a reclamation of a complex future for those pictured, with both “respectability and swagger.” For Campt, the seeming stasis in these images invites investigation, pulls the body closer, and makes a demand that exceeds ethics. The images are quiet, Campt insists, but if one listens with their gut to the low frequencies so inaudible that they may only be felt, they have stories to divulge. The photographs are imbued with desire and need—a futurity that is not just about surviving, but about living with resilience and joy in the grammar of that which hasn’t yet happened, but must.