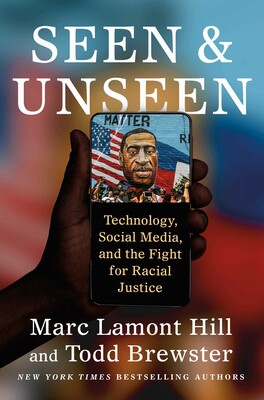

When Darnella Frazier recorded the execution of George Floyd on her cell phone, she was entering into a long tradition of citizen sourced reporting that has helped shaped our ideas around race and state violence. In Seen and Unseen, journalist and professor Todd Brewster and journalist and professor Marc Lamont Hill wrote about how cell phone footage once again was able to mobilize people into mass action. I spoke with authors about their new book Seen and Unseen and about how technology has both expanded and shrunk our ideas around race.

Where did the idea for Seen and Unseen come from?

Todd Brewster: It came out of a conversation that Marc and I had a couple of years ago shortly after the George Floyd murder. Like everyone else, we felt the shock over what had happened in Minneapolis and I think both of us wanted to find a way to write about it in some way to help us make sense of it. We realized that to some degree what had happened with George Floyd was dependent upon the video that had been done and that without the video we probably wouldn’t have seen the same kind of outcry over the killing of George Floyd. We wanted to mine the meaning of that and exactly how that happened.

Marc Lamont Hill: You know, our conversations. Todd and I are friends and we talk about the world and we talk about what’s going on and we also were, to be quite honest, thinking: what should we write about? Let's write a book together. Let's do something. And it was impossible to be in this moment in America, in the middle of a pandemic, and not bear witness to what was happening in the streets of America in response to the death of George Floyd.

While cell phone footage is new, it certainly isn’t new how average citizens have taken it upon themselves to record in some capacity instances of racial violence. You mention Ida B. Wells in the book and one could argue that other moments like Mamie Till having an open casket funeral for Emmett, Billie Holiday singing Strange Fruit, and journalists documenting the brutality that took place at the Edmund Pettus bridge follow in this tradition. Can you briefly discuss the ways average citizens have documented racial violence that has transformed our conversations around race?

MLH: I think part of what everyday citizens have done is draw on — what we call in the book the “spectacle of death.” We want to draw people to our case, to our cause to our agenda by putting a spotlight on sometimes the most horrific incidents and hope that it can stir human consciousness. That it can shape the way people will see. When Dr. King decides to stage a civil rights action on the Pettus bridge. It's because he knows that the violence that will be visited upon them will have some kind of impact on at least some slice of the American public and that they'll respond to it. When Emmett Till was killed in ‘55 and his head is disfigured his face is unrecognizable, multiple times its normal size, and Mammie Till wants to have an open-casket funeral and she does so it's because she knows that the public reaction to that can help galvanize. And so the technology becomes a tool for helping people to see it, right? The television and the newspaper help people see what happens when with Pettus Bridge. Jet Magazine becomes an important avenue for us to see what happens to Emmett Till's face. Nightly news helps us see the beating of Rodney King and our social media helps us watch the murder of George Floyd. And so everyday people have drawn on the technology to draw attention to the spectacle, to stir at our emotions in our conscience.

TB: Really Darnella Frazier, who was the young woman who did the most-watched video of George Floyd, is in a long line that goes back to Ida B Wells, but then marches all the way through in the past 150 to 200 years of American history of people being willing to actually show what they see with their own eyes. Just the tools we have now are so much richer and give us so many more of us, the opportunity to be able to do that.

The first time camera footage was able to galvanize the country into a discussion on race and policing was the Rodney King assault. Do you remember the precedent that set and what was the conversations that sparked?

MLH: I'll tell you for me I was coming of age at that time. And for me, the Rodney King video was like a moment of me saying, “oh my God, see! This is what we've been talking about.” Like that this is our proof. And I remember thinking, in all the conversations that were going on – and again, this was pre you know, 24-hour cable news everywhere, pre-social media – so when nightly news, when they talked about it, when I read about a newspaper or listen to local radio in Philly, everybody was talking about this case and everybody was talking about, you know, what was going to change after these officers got found guilty. And I remember even my Uncle Bobbie, who was sort of my race Puba at the time was like, “don't be surprised if they don't find them cops not guilty. Don't be surprised if you don't get what you think justice is.” But I thought the technology made the case. I thought the video camera made the case. And so for me, when the first trial happens and we don't get the kind of justice we expected for me, I mean, I was devastated. I was trying to figure out the world at the time and I was like, wait a minute, I thought the only thing we needed was proof? We need more than that. We need proof. We need will. We need people to look at the proof the way I look at the proof. We need all these other things to happen too. And so for me, that first moment is powerful in a sense that it called America's attention to something and it, and it, and it changed hearts and minds. It was indispensable, but it was also insufficient. And I think that's the way I think about technology always in the fight for racial justice.

TB: One of the compelling things we learned in this book and certainly it's a story that follows American's relationship with technology from the beginning but just because you see, as Marc just said, doesn't mean that the person that's sitting next to you sees the same thing. And so we see with eyes that are that have been filtered in a way and to accommodate our particular views on the world. That doesn't mean we don't grow. It doesn't mean we don't develop. I always say to my students about the First Amendment: Yes, you can say anything you want to say – with some qualifications – but the responsibility for the other person to listen and for them to be willing to be changed by what they hear. Willing to be changed by what they hear and willing to be changed by what they see. Are you willing to do that? Are you willing to work at the world anew tomorrow differently from what you did today? Because the evidence may be different that you're seeing now. And that is what I think we have to bring to our technology.

It might be impossible to remember now, but after the execution of Breonna Taylor, her death took a while to gain mainstream momentum in the same way that Ahmad Aubrey who was killed just a few weeks prior did and certainly not the way George Floyd’s immediately thrust everyone into action. There were people who suggested that because her death was not caught on camera, there was no way of knowing what happened. In this way, one could argue that the advent of footage into conversations around policing only hinders our ability to meaningfully engage in police and state violence. How do you respond to that idea?

MLH: I don’t buy that because that would presume that somehow before the technology, people were believing the random Black witness or that somehow law enforcement were piecing together these cases against themselves of state violence against Black people and that somehow we've gotten so addicted to video that now that's the only way we'll prosecute a cop for shooting a Black person, but before we’d build a case. It's like, nah, they weren't building a case before. It wasn’t like there was this whole long tradition of cops and other law enforcement personnel being held accountable for the killing of citizens.

And so I agree that now we're certainly susceptible to only believing something when we catch the officer on tape or when we have live audio footage. I see how that could become the new standard and in many ways, it has become the standard for how we talk about police officers in particular. But again, it's not like we were successful before, so I don't see it as a kind of con, as a negative. Rather, I see it as a good starting place. To me, the conversation can't be okay “whenever we catch cops on, on tape shooting us, they should be prosecuted.” The conversation should be, “'cause we keep catching cops on tape doing stuff, maybe we should believe that the relationship between police and citizens is more complicated and messy than we thought before.” And so then maybe we need to have new policies and practices and procedures to hold everybody accountable in a different way.

TB: To add to that, I think we still have, despite whatever evidence we may have, there's an institutional bias. There's a bias that says the institutions, because they’re institutions, do things right. And that of course is wrong. I mean it's never been true and it never will be true. Institutions are human creations and they're as flawed as human beings are, they're filled with some of the same tendencies, all the rage, all the same biases, all the same racism that we might find in the popular society. That's what Marc was speaking to. To go from the micro to the macro and to say, all right, well, what does this tell us about the broader question of policing?

After the murder of Mike Brown, body camera footage was positioned as a revolutionary reform taken in order to curve police violence. But aside from the fact that cops can turn off their cameras whenever they want, state-sanctioned footage can often be edited and police often engage in gaslighting where they try and convince the public that what they are seeing isn’t what’s happening. What are your thoughts on body cameras and how they haven’t caused the systemic change people were hoping for?

MLH: I think it goes back to what Todd just said, the technology is only a piece of it. People have to have a commitment to understanding the technology or the footage. They have to believe in it. We all bring something to the film that we watch. We all bring something to the photograph that we look at. And so it's not enough to have the body camera. Because we've seen body camera footage that half of America thinks means one thing and the other half thinks means something else. So I never want to make a fetish out of technology. I never want to ascribe magical power to any technology. I think again, there are tools that we can use, you know, but at the end of the day, we have to ask, I think, more fundamental questions about the context in which those tools are used and the systems to which those tools are assigned a certain kind of surveillance power.

TB: I would agree with Marc completely. I think that the fetishization of technology leads us to think that everything should be surveilled. And of course, that's a kind of a scary notion in and of itself. I do think that the bodycam footage has been illuminating but it's one tool of many. And it comes back to this question of: we can examine the symptoms, or we can look at the disease. There's plenty of Black police officers who have institutional bias too. There's a lot to be understood in that and I think we need to step back and take a look at the broader picture. And that's what I think all these episodes are telling us there is something happening. That is it.

The bodycam footage can be an agent to change, but it's not going to make the changes.

There has been debate about how cell phone footage of Black people being murdered not only triggers Black Americans who are already well aware of state violence, but the endless loop they often play on only desensitizes viewers. It also bears remembering that it was only two or three generations ago that white people were attending lynchings like it was a family outing and even today there are white families that attend death penalty executions, so it’s definitely not enough to elicit mass white empathy. Where do you stand on this?

MLH: I think it's complicated. I think this is a battle that we always have. You know, people, there are people on the internet right now who showed videos of police shootings and some people say they're exploiting Black death. Other people are saying, that they are putting a spotlight on issues that we need to care about.

People had that debate about Ida B Wells. What do these photographs mean? How does keeping track of lynchings in America either desensitize us or trigger or sensitize us to these issues. It's a constant debate and I don't think there's a simple answer to it but I think it's something that we have to be mindful of when we engage these technologies.

I’m sure you’ve seen the news that Elon Musk has bought Twitter, or at least plans to. There’s been worry from a lot of activists that the platform will become a hostile environment for the kind of organizing and radical education while others have made the point that Twitter – along with other social media websites – has never been a safe space for radicals to peacefully exists. What are your thoughts on this?

TB: Yeah, I'm concerned too. I'll let Marc speak more to that. I'm pessimistic.

MLH: I share Todd's pessimism on this. I think like you said, there's a way that these spaces do create opportunity and possibility for folk to engage. But I think we can never underestimate the amount of oversight, the amount of surveillance, the amount of corporate power, all the things that are also operating at the same time that I can talk about radical politics on Twitter or whatever the thing might be. And so when you take something that's a relatively public sphere and again, it's not a perfect public sphere – they never are – but if I take something that's relatively public and then I privatize it and then I regulate it, even if it's for the good “Oh, free speech everywhere for everybody,” “Anybody can say anything now nothing will be regulated,” or these are some of the things that Musk is talking about, that can bring great detriment to many of us.

And you're right, no place is safe, no spaces, entirely safe. There's always something at stake. There's always power dynamics at play. But if you tell me that now there's not going to be any regulation, what does that mean for the white supremacists who can just continue to assault me and attack me? What does that mean for the anti-Semite who can threaten folk? What does it mean for the person who advocates something that we might all find morally objectionable, but might not be technically illegal? Like something like certain types of violence against children? Do we want to live and work in that space? For me? The answer is no. And I worry that we can have more of a wild, wild west field out there.