A generation beleaguered by insecurity has lifted thimble-covered middle fingers to the “new normal”

At the tender age of 28 I learned how to sew, thanks to the impulse-purchase of a pale pink Singer 401A Slant-O-Matic sewing machine off Craigslist. It was the very picture of Eisenhower-era stolidity, boasting six cams and a buttonholer. Service it regularly, the former owner assured me, and it would work 'til doomsday. I admit I didn't quite know how to make use of such a doughty device, but I liked its looks. It stood on display in my living room, next to the futon, where I could admire its sturdy profile and clean lines. It added to my otherwise musty apartment a comforting aroma of machine oil.

Soon, however, a few secondhand sewing instruction books sent me from admiring my machine to using it. Every day I practiced hemming, back-tacking, and ruffling. My perfectly earnest efforts produced decidedly imperfect results -- lopsided dresses, wadded-up skirts, irregular napkins -- but filled me with a sense of accomplishment. I wore my homemade outfits everywhere, their crooked hems and puckered pockets bothering me not one bit.

Those evenings with my old Singer came back to me as I read Homeward Bound: Why Women Are Embracing the New Domesticity. In this recently published book on the current rage for things handmade and homegrown, author Emily Matchar looks at "how crafts like knitting, sewing, and embroidery have staged a comeback." This comeback she christens the "New Domesticity," and it extends beyond handicrafts to encompass, among other things, "DIY foodie culture that has so many of us baking our own bread and raising chickens in our backyards." Behind this movement lurks "growing disenchantment with the mainstream workplace, which has failed young people, mothers, and families in so many ways." A generation beleaguered by high unemployment, job insecurity, low wages, and paltry benefits, have lifted thimble-covered middle fingers to this "new normal." Instead of lobbing Molotov cocktails, they're putting up preserves.

Matchar sticks largely to the distaff side of the New Domesticity: Women, she points out, continue to make most domestic decisions. They still buy food and, at least 78 percent of the time, still cook it. She does note, however, that many men would rather knead dough than push paper. One young man she spoke with taught himself to cook and sew in preparation for eventual homestead life. A second admitted he'd like nothing more than to swap places with his stay-at-home wife. A third actually lived the second's dream, happily keeping the house his breadwinning mate returns from the office to. This shift away from brisk career building does not represent a shift toward sloth. Quite the opposite. "[T]he home economics of our grandmothers," observes Matthew Crawford in his 2009 bestseller, Shop Class as Soulcraft, is really about a struggle to find purpose in an increasingly impersonal high-tech culture, a struggle occupying "the very center of modern life."

Modern life's miseries have simply inflamed an otherwise long-abiding desire to find purpose in homemaking. Matchar offers only a brief historical background of the cult of domesticity, which is understandable, since her book’s purpose lies elsewhere. But America's post-Revolutionary years were enormously fertile, if brief, as far as enlightened homemaking is concerned. In it were born ideas about domestic happiness and liberty that resonate today. A consideration of it reveals that what today’s homeward bound chase isn't so much a fad as it is a rediscovery of a longstanding ideal. Contemporary American culture may have made this ideal somewhat trite or banal, but to those legions of picklers and knitters it retains integrity enough to impart some to their lives. "It's really fulfilling and sort of empowering," remarks one of Matchar's subjects, a 29-year-old housewife, "the idea of 'Here's dinner on the table' -- I grew it, I cooked it, I served it on napkins I sewed." The wisdom in late-stage capitalism's swingin' years was that nothing excels like excess. Several recessions and "lost decades" later, you could say that nothing satisfies like self-sufficiency.

Indeed, the exaltation of excess proved something of a historical exception. Post-Revolutionary Americans tended to esteem self-sufficiency as a rule. They believed that happiness began at home. When the Polish count Adam G. de Gurowski visited the United States in the 1850s, he made a close study of American domestic culture. He took note of the inhabitants' manners and customs, their way of living and working together. He saw that Americans enjoyed an unusual degree of familial intimacy and concluded that the "domestic hearth, the family joys and hardships, must have formed almost the exclusive stimulus of existence for the first settlers." Therein "they concentrated all their affections and cares," Gurowski mused, and therefore "stand out best in the simple domesticity of family life."

Gurowski's impressions were spot-on. When colonists first set foot in the New World, they found a desolate scene. Of his fellow pilgrims William Bradford remarked that they had "no friends to welcome them" nor "any houses or much less towns to repair to." They lost no time in wresting what comfort they could from the wilds. Some lived in little more than caves and wigwams, while others sought shelter in "rotting wooden affairs that lay about the landscape like so many landlocked ships," as historian Edmund Morgan put it. But no matter how inadequate or makeshift, all these shelters contained a hearth in one form or another around which family life revolved. By the hearth frontiersmen and -women ate, by the hearth they slept. Cramped and dirty as it was, the hearth offered a degree of comfort and safety against the wild outside, and that's all that really mattered.

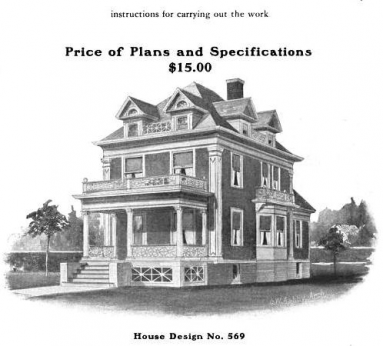

By dint of its primary role, the hearth -- and, by association, the home -- assumed mythic proportions in the American imagination. It wasn't until the time of the Revolution, however, that Americans could make more of their home lives, and they did so with gusto. Independence allowed many to achieve a measure of domestic security, and evidence of new prosperity could be found everywhere. In Philadelphia and Boston sprang up Georgian houses, big airy buildings that divided the domestic space into separate areas -- bedrooms, parlors, dining rooms and the like. (The Georgian home so perfectly fitted middle-class needs that it has continued to symbolize the American home right through the twentieth century.) So many rooms bred a need for interior decorating. Proud homeowners crowded them with sofas, clocks, rugs, paintings, chandeliers, and various tchotchkes. One home on Cape Cod boasted a chopping block fashioned from the cervical vertebrae of a large whale. There were tables too, lots and lots of tables: side tables, breakfast tables, tea tables. The space upon these tables also had to be filled, and upon each were place settings for each family member (a novelty) along with water ewers and wine decanters, teapots, coffee pots and chocolate pots. By the 1790s some 90 percent of homes in Chester County, Pennsylvania featured tables and chairs and all the necessary accoutrements, whereas before 1670 only half of Americans owned such commodious homes, with most families crowding into whatever room was warmest to slurp in common the evening pottage.

Georgian homes embodied in their architecture popular philosophies of the time. Their many rooms not only spurred increased consumption of household items but allowed families to cordon off certain domestic functions, as well. A broad hall ran through the center of the house, with two rooms opening out on each side. A staircase led to an upstairs hall, also flanked by four rooms. No longer was it necessary to eat, sleep, and bathe in a single room; the layout of Georgian homes allowed each activity to take place in separate spaces. More importantly, it separated rooms intended for working from those for living. Cooking and other dreary tasks took place in one room, eating in another, and family entertainment in yet another. Work spaces could be hidden out back or tucked away in the main body of the house. A cellar could enfold a kitchen; a garret, servants' quarters.

Separation of household work also inspired new ideas about separation of individuals -- a revolutionary idea otherwise known as privacy. Combining themes elaborated by philosophers John Locke and Jean-Jacques Rousseau and novelist Samuel Richardson, new social and economic philosophies championed an individual's right to solitude, and enshrined domestic autonomy as the home's chief virtues. As early as 1690, William Penn, the Keystone State's namesake, wrote that it is "the Advantage little men have that they can be private, and have leisure for Family Comforts, which are the greatest Worldly Contents men can enjoy." Intensely private in its pleasures, the ideal family esteemed love and learning over older values such as property, lineage, and labor. Mothers and fathers cherished one another as individuals, and together they nurtured in secluded comfort their children, the future citizens of the republic.

This new domestic philosophy granted such events as mealtime distinction as occasion not only for nourishment, but for relishing in tranquil privacy all those tangible and intangible qualities -- art, friendship, generosity -- believed to foster enlightened, virtuous individuals. Americans delighted in their rather unique domestic culture, which often surprised guests. Foreigners marveled at American etiquette, especially when it concerned children. An Englishman taking tea with one family found himself in rather unkempt company. "[The] children's faces were dirty," he notes, "their hair uncombed, their disposition evidently untaught." A youngster's soiled, rumpled and uncouth aspect apparently owed to his becoming "too early his own master," as another visiting British subject observed. Nowhere was this premature self-mastery made more evident than in the fact that the child "chooses his own food." Yet a third sojourner, Mary Grey Duncan, writes that "each child obtains a seat at the family table at meals as early as they can be trusted in an elevated chair." Once they have achieved this station, "they are used to ask for and to receive all manner of varieties of food," including oysters, jellies, and ices, fruits, and preserves." Shocking as this behavior was, it was wholly consistent with respect for individual rights. Every bit as much citizens of the young republic as their parents, American children found themselves free to eat what and when they pleased, even if it meant incurring a tummy ache and offending foreign guests.

Meals were a time to indulge in home life's pleasures, not to ape foreign manners. Women especially took great pride in cultivating a vigorous and enlightened domestic culture. The housewife dishing out apple pie wasn't simply feeding her brood; she was schooling them in self-sufficiency and humane sentiment. Old World recipes, with their taint of aristocratic pomp, she held in contempt, favoring instead dishes of native foodstuffs as forthright and unostentatious as she considered herself to be. For guidance, she turned to such books as American Cookery (1796), thought to be the first cookbook prepared by a daughter of the soil. It offers many recipes pitched to a revolutionary's sensibility -- Election cake, Independence cake and Washington pie, to name a few. Three decades later, she could turn to Lydia Child's The American Frugal Housewife, a tome containing not only specifications for preparing various dishes but also guidelines for proper management of a republican household. Child inveighs against sloth and acquisitiveness. "A luxurious and idle republic!," she exhorts readers: "Look at the phrase! -- The words were never made to be married together." Such salty rhetoric she leavens with helpful household hints ("Boiled potatoes are said to cleanse the hands as well as common soap."), health maxims ("Rise early. Eat simple food. Take plenty of exercise," along with quite a few borrowed from Benjamin Franklin), and uniquely American recipes for everything from cranberry pie to baked Indian pudding and fried salt pork. Every item in The American Frugal Housewife eulogizes some facet of the stereotypical American character -- industry, frugality, good eating, independence -- and does so for the express purpose of promoting the survival of those virtues unique to the new nation.

In matters and manners domestic the United States stood for the most part unparalleled. In 1771, a Scottish farmer called it "the best poor man's country in the world." Those who prospered found their lives even more satisfying. During his years of exile in the United States in the 1780s, French gourmand Jean Anthelme Brillat-Savarin came across a Connecticut farmer. This man, a "worthy landowner," presided over a generous portion of "the backwoods of the State" teeming with "partridges, grey squirrels, and wild turkeys." Each night he dined on corned beef, stewed goose, and magnificent legs of mutton. He consumed "root-vegetables of all kinds," and quaffed "enormous jugs" of delicious cider. The farmer was lucky, and he knew it. "You see in me," he said to Brillat-Savarin, "a happy man, if such there be on earth ... everything around you and all that you have so far observed is a product of what I own." This abundance he attributed to just government and civil peace, and says that "here in Connecticut there are thousands of farmers just as happy as I am, and whose doors, like mine are never bolted."

Brillat-Savarin didn't pay much heed to the farmer's words. He was, he admits, more interested in how best to cook the turkey he had bagged. But they nonetheless capture the optimism and joy that comes with living in a prosperous new nation. For the first time, people could make of their lives what they would. (Of course, this was true only for white, landowning men.) "It is not a question of building vast palaces, of vanquishing and outfitting nature, of depleting the universe in order to better saturate the passions of a man," another visiting Frenchman, Alexis de Tocqueville, wrote of American domestic life. Rather, he continues, "it is about adding a few toises to one's field, planting an orchard, enlarging a residence, making life easier and more comfortable at each instant." Those with means to enjoy these simple pleasures did so, cultivating a rich and rewarding home life they felt mirrored the values of enlightened, democratic society.

Yet as many were beginning to taste this free and easy life, the forces that would undermine it were already under way. The decades leading up to the Civil War saw the United States transformed by manufacturing. The rate of industrial growth between 1815 and 1840 outpaced even that of the years following the Civil War. The economy no longer driven by agriculture, the portion of the labor force outside farm work increased from 17 to 37 percent. The country had entered the Machine Age. Abetted by a transportation revolution, which birthed turnpikes, canals, steamboats and railways, per capita domestic product rose some 60 percent. Urban areas grew and spread outward. A city of some 750 residents in 1800, Cincinnati, Ohio numbered 161,044 souls by 1860. Factories multiplied. Newly arrived immigrants swarmed to fill them, their numbers doubling, then doubling again, in the two decades between 1830 and 1850. Such were the rates of economic and population growth that by 1840 the United States ranked as the second greatest industrial power in the world.

Industry transformed American society by precipitating a shift from a landowning, largely independent population to one dependent on wages. Historians Allan Nevins and Henry Steele describe the birth of a new American elite, "a vulgar, brassy greedy element ... eager for money and power, coarse in their tastes, and unscrupulous in their acts." With their rise poverty grew. Whereas colonial settlers had equated poverty with inability to work, a problem limited to the aged and infirm, this condition pre–Civil War Americans regarded as a defect in the nature of work as it had come to evolve. Competition, irregular labor demand, the wage system, and regular boom-and-bust cycles all ensured that an able young shaver would as likely endure unemployment as any arthritic graybeard. As early as the 1790s the underemployed could be found wandering cities. Masters and apprentices had been consigned to the annals of history along with British rule. In Industrial Age America, he who began life earning wages likely ended life earning them.

This growing inequality would eventually shape American domestic culture. Matcher writes that, during the mid to late nineteenth century, the ideal wife was the “angel in the house,” a woman “sweet, submissive, [and who] wanted nothing more than to serve her husband and children through her domestic labors.” The home still functioned as a private reserve, but its inhabitants’ ambitions were more personal than political. A society hardened into class strata gave people little opportunity or inclination to share political and social ambitions. For postbellum Americans, retreat into privacy was more about shutting out social inferiors than it was about opening grand democratic vistas.

Now we're throwing up those barriers again, as policies steering the country away from New Deal reforms have had time to work their effects. This, Matchar believes, is a mistake. She warns against beating a retreat to our homes "the way the women of the original nineteenth-century Cult of Domesticity did." With the gap between the have and have-nots in the United States at its widest in a century, this observation alone makes Homeward Bound worth reading. "While we want to believe that 'all change begins at home,' this is not necessarily the case," Matchar writes, "even if it were, all change needs to not end at home." If we're to take a cue from the past, it shouldn’t come from those reclusive Victorians, who were so intent on shutting out the world, but from the idealistic members of the young republic who believed that home was a place to bring up informed, politically engaged individuals. “A house is not a home unless it contains food and fire for the mind as well as the body,” wrote Benjamin Franklin. On balance, the New Domesticity is, as Martha Stewart might say, a good thing. It offers individuals and families means to resist the social and economic ills that plague them. For that resistance to bring about lasting change, however, it must also foster those private pleasures which breed public virtues.