Black women's anger towards supposed allies is never taken for the self-preserving force it is

To turn aside from the anger of Black women with excuses or the pretexts of intimidation is to award no one power — it is merely another way of preserving racial blindness, the power of unaddressed privilege, unbreached, intact. Guilt is only another form of objectification. Oppressed peoples are always being asked to stretch a little more, to bridge the gap between blindness and humanity. Black women are expected to use our anger only in the service of other people’s salvation or learning. But that time is over. My anger has meant pain to me but it has also meant survival, and before I give it up I’m going to be sure that there is something at least as powerful to replace it on the road to clarity. —Audre Lorde, “The Uses of Anger: Women Responding to Racism”, 1981

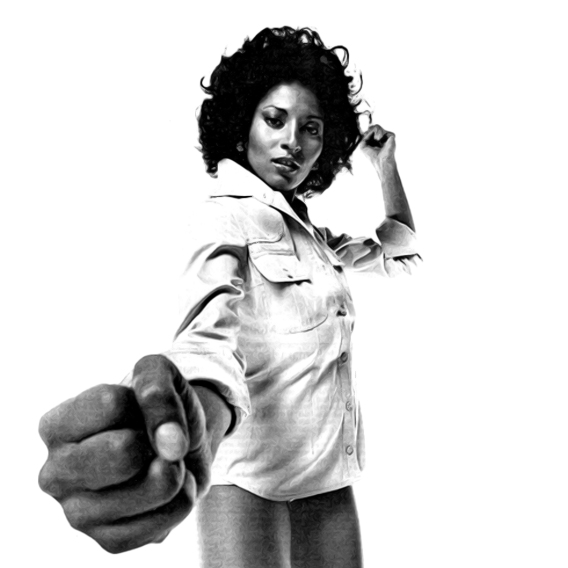

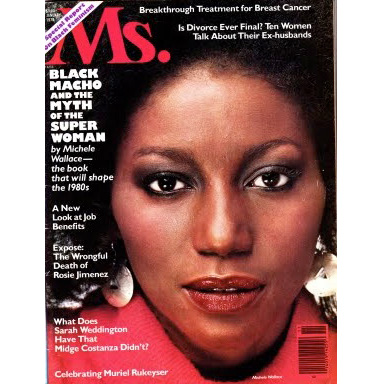

In January 1979, Michele Wallace became the first Black woman to grace the cover of Ms. magazine. At the cover photoshoot, Wallace, who wore her hair in braids, was instructed to take them out. As Wallace tells it, the magazine’s stylists thought her braids would “ruin” the cover. She complied, but found the hairdresser had no clue what to do after taking her braids out. Not understanding how to style a Black woman’s hair, but unwilling to let Wallace decide how to appear on the cover, disallowing her braids was the extent of the plan to style her for the cover shoot. In the end, she was photographed with minimally styled, natural hair (most of which was not visible in the picture) and heavy makeup. Wallace regretfully recounts the heavy handed makeup artist on the shoot: “The makeup artist applied layer after layer of a various assortment of foundations trying, I can see now, to somehow brighten my hopelessly olive Blackness. People say this is a beautiful picture but I can’t see it. I hated it.”

The landmark Ms. cover was dedicated nearly entirely to promoting Wallace’s then-new, much-talked-about Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman

Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman

by Michele Wallace

Foreword by Jamilah Lemieux

Verso Books

Paperback

288 pages

June 2015

Many of the ideas the book deals with — racist misogyny, sexism within the movement, Black family relations — have resonance today. With movements fighting state violence against Black women like Sandra Bland, it is clear that the intersection of patriarchy and white supremacy still has deadly consequences in America. It comes as no surprise that the book has earned its place as a much loved treatise amongst Black feminists; it is a survival tome. The arguments Wallace introduced into the public sphere possess a singular merit derived from the author’s rage. For Black feminists then and now, Black women’s anger has a purpose — it is useful both personally and politically. Black women’s anger is raw and immediate, imbued with the roughness of having survived multiple oppressions, demanding visibility when America would rather we die quietly. And that’s the loudness of the fury written into Wallace’s pages. For the author, Black women’s anger is — in the tradition of Audre Lorde — a kinetic force. Anger provides an honest space for the possibility of social movement instead of stagnation. Anger is, as Lorde writes, “a grief of distortions between peers, and its object is change.” Wallace’s “necessary roughness” and her anger is in every sense a balanced reaction to her lived experience and observations of the distortions white supremacy has created between Black men and women. Black Macho is a more than even-handed take when one considers the full weight of white supremacy and patriarchy in America.

***

Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman is a conceptual diptych. The book interweaves history, cultural narratives and archetypes, popular culture, and the author’s personal anecdotes to tell a story in two parts. Part one offers a picture of the Black man — a being whose biopolitical destiny can be located squarely at his penis — and part two is a picture of the consequences that bind the present for Black women. Wallace lays the failures of the Black Movement at the feet of white supremacist patriarchy, and she is unsparing in her indictment of the violences committed by Black men. Wallace reminds the reader that during the Black Movement, many women organizers were subjected to “an inordinate amount of typing, coffee making, housework” — a condition which was made even more degrading by the fact that their fellow male organizers singlemindedly pursued white women who came to work with the movement during Freedom Summer in 1964. Wallace quotes SNCC organizer Cynthia Washington: “we did the same work as men —organizing around voter registration and community issues in rural areas— usually with men. But when we finally got back to some town where we could relax and go out, the men went out with [white] women.” Washington was not the first to protest the hypocrisy of a Black Movement which privately desired whiteness — other members of SNCC reportedly voiced concern to the leadership to no avail. For the Black woman, the Black man is the ultimate in practical disappointment. He does not forsake her in any grand romantic sense, rather he denigrates her, mocks her, beats her, and abandons her at the most dire moments in order to actualize himself under the toxic and impossible structures of white supremacy and patriarchy. These personal psychic failures would become manifest as political shortcomings in the Black Movement, a movement which Wallace primarily experienced secondhand. Still, for Wallace, a Black Movement that negated the contributions of Black women could be reduced to “just a lot of Black men strutting around with afros."

Wallace’s concept of Black Macho is constructed from her personal observations and interrogations of texts she freely admits are deeply flawed in their arguments — Norman Mailer’s “The White Negro”, for example. Critics of Black Macho — June Jordan chief among them — found Wallace’s use of Mailer’s observations about Blackness in her book deeply problematic, given that she did not interview a single person involved in the Black Movement. To be sure, this is the major failing of the book. For many, the argument about how Black relations were shaped by white supremacist patriarchy was overshadowed by Wallace’s methodology, and “airing the dirty laundry” of the movement to white critics. While the former is a reasonable criticism, the latter cannot be, particularly if the Black Movement in its current iteration is to create conditions for revolutionary rage that are inclusive to people of all genders and orientations. Lorde’s explication on the uses of anger, which I read as an intertext to Wallace, asks that we reframe our rage not as safe but as separate from patriarchy and toxic masculinity. Lorde writes, “For women raised to fear, too often anger threatens annihilation. In the male construct of brute force, we were taught that our lives depended upon the goodwill of patriarchal power. The anger of others was to be avoided at all costs because there was nothing to be learned from it but pain.” Wallace’s text answers Lorde’s call to be angry, to act with the knowledge that Black women’s anger is generative and not destructive, as we are taught to fear.

***

American Blacks are not more psychopathic, as a group, than are white Americans, and the evidence would indicate that they’re a good deal less so. But there is the matter of that kind of violence I have described, typical of all ghettos, specifically Black ghettos, and devastating not because of its frequency but because of its unpredictability, and if one thinks carefully one will realize that it was precisely this kind of violence...that’s actually occurred during the Black Movement. The rest was bravado... there was very little actual violence directed at the so-called enemy. But then there is more to the psychopath than his willingness to take lives. And if one accepts a psychopath as one who is ‘incapable of exertions for others,’ and accepts that ‘all his efforts … represent investments designed to satisfy his immediate wishes and desires,’ one would have to say that there did seem to be a curiously psychopathic energy at work in the Black man’s pursuit of this manhood during the sixties. But...as Mailer points out, being a ‘rebel without a cause’ was not a position that the Black man freely chose but one he’d been forced into. That is, in the face of a machine that limited and confined his existence to the most purely physical, that had perfectly worked out and planned his helplessness, what other choice had he but to focus upon those things that could be his advantage alone — unpredictability, virility, and a big mouth, which is all any kind of macho really is when you come down to it. One could say the Black man risked everything — all the traditional goals of revolution: money, security, the overthrow of the government, in the pursuit of an immediate sense of his own power.

The passage above crystallizes Wallace’s most salient points about Black Macho and the failure of the movement — and more importantly, places them in context. For Wallace, Black Macho is not a biopolitical destiny that the Black man chose for himself, but that fact does not mitigate the destructive effect of its toxic masculinity. There will always be a price to pay if you want to be a man, Wallace reminds us, and under white supremacy, it will come at someone’s else’s expense. Instead the author asks us to consider what Eldridge Cleaver’s famous pronouncement, “we shall have our manhood...” has meant for Black women of the movement. When the Black man has fallen victim to the discursive trap of macho, where does that leave everyone else? For Wallace, the answer is high and dry — relations between Black men and women have been strained by decades of resentment and insecurity stemming from the indecipherability of structural violence in America. The psychic distortions between peers that Lorde and Wallace identify have existed between Black men and women for as long as white supremacy has, but before Black Macho were not legible to those affected. Or if they were, there was no common language with which to have the conversation. The discursive effects of power on social relations are self-concealing. Today, the concepts mapped in Black Macho are standard fare, taken for granted as ideas we can talk about as Black people. Before Michele Wallace got angry and wrote a book, not only were these conversations not happening — it was unclear how to begin having them. The anger Wallace writes into Black Macho created a rupture that allowed for kinetic energy, and for forward movement in conversations about relationships amongst Black people.

The state cultivated the destruction of the Black family unit well beyond slavery. Paternalistic government policy would unravel the Black family unit around the time of the Black Movement. Not only were Black people of all genders denied equitable employment, underemployed families were often separated in order to access the social safety net. It was an early condition of welfare programs in the 1960s that Black women be unwed, and that they not cohabitate with male partners at the risk of losing social support for the family. So when the infamous Moynihan report came out in 1965, it stoked a fire that was already burning in Black homes. The report — named for its author, the Assistant Secretary of Labor — claimed that “the Negro community has been forced into a matriarchal culture [which] imposes a crushing burden on the Negro male … and seriously retards the progress of the group as a whole.” Black policy experts, community leaders and scholars immediately decried the fact that “Moynihan was trying to take the responsibility for racism off white shoulders, where it belonged, and place it on blacks themselves.” But despite the outcry against Moynihan, Wallace writes, “no one would admit it, [but] Moynihan had managed to provide authoritative support for something a lot of Black men wanted to believe anyway.” Add to this the private violences Wallace names, the politics of desirability chief among them — Black men chasing white women or disdaining queerness — and the picture of frayed relations is complete. In the years since Moynihan, public policy experts have looked at the data on Black families and concluded that the report was at best misleading. In a paper published by the Rockefeller Foundation, Erol Ricketts explains that “the data show, contrary to widely held beliefs, that through 1960, rates of marriage for both black and white women were lowest at the end of the 1800s and peaked in 1950 for blacks and 1960 for whites. Furthermore it is dramatically clear that black females married at higher rates than white females of native parentage until 1950.” The problem, of course, was never that Black men and women weren’t getting married — rather that marriage doesn’t act as a salve for structural racism.

The second half of Wallace's conceptual diptych is even more impactful than the first — the book is more of a meditation on the state of Black women than anything else. Wallace paints the reader a picture: out of the crucible that is racism and sexism in America emerges a mythic creature. She is invulnerable, indelicate, can work endlessly without tiring or complaint, and is sexually promiscuous. She is a complement to Black Macho. Her origin can be traced to slavery and to enslaved women who were the foundation for the labor force, their wombs the site at which capital was produced. And this woman — a Super Woman — does not belong to the Black man, but has allegiance to the white slavemaster instead. “Every tenet of the mythology about her was used to reinforce the notion of the spinelessness and unreliability of the Black man,” Wallace writes. The Superwoman also serves as a conceptual foil to white womanhood which endures as delicately emotive, and something to be protected at all costs. Wallace argues that the Superwoman construct was a means through which to alienate Black men and invisibilize the humanity of Black women. The Superwoman reminds the Black man of his own oppression; there is no imperative to protect her. Despite the construct’s critically flawed premise and lack of statistics to back it up, Moynihan would confirm the Black man’s resentment and couple it with the idea that the Black woman somehow had more than him to call her own. Of this subterfuge Wallace writes, “[the report] never actually said that the Black woman had more. That was left to Black men who knew the contents of the report through second and third-hand sources. All Moynihan actually said was that she had too much.”

***

In Marlon Riggs' final film Black Is...Black Ain’t, Michele Wallace tells the filmmaker that she believes the Black community has punished her for publishing Black Macho and the Myth of the Superwoman:

MICHELE WALLACE: I just think that black feminists have not been good at critiquing the black male sexism. Because of the oppression that we suffer as a people, I think that it just becomes the job no one wants to do. You know, everybody knows about it. It's well known. It's well understood by black women and black men ... and yet, nobody is supposed to speak about it publicly. I did so. I think that, you know, was sort of the significant departure.

MARLON RIGGS: And you were punished?

MICHELE WALLACE: And I was punished for that, yes. Yes, I was punished, (pause) that's true, still being punished actually, I think.

The interview in Riggs’ film — a documentary exploring the discursive limits of Blackness — was not the first time Wallace complained of the slights leveled at her from prominent members within the community of Black creatives and organizers. Wallace paid the price for writing Black Macho, even as it was a necessary and welcome intervention for so many Black women. The racist and sexist mythic discourse America cultivates between Black men and women which Wallace so precociously maps — she was just 26 when the book came out — was of course manifest in the Black Movement in many ways. And yet when Wallace writes of the Black Movement, “When the Black man went as far as the adoration of his own genitals could carry him, his revolution stopped. A big afro, a rifle, and a penis in good working order were not enough to lick the white man’s world after all,” it reads as bluntly uninterested in the history of a movement which was in decline before she was a teenager. Perhaps this is a byproduct of dealing in archetypes and myth. Wallace’s assessment is an oversimplification and a dismissal of the size, scope, and import of organizing that took place within the Black Movement — even erasing the very real contributions of Black women to the movement in the name of saving them, rhetorically. The reader today might ask herself if it’s even possible to look towards the future of Black relations intelligently without considering the history of those same relations with at least a little care. In her New York Times review, June Jordan wonders why Wallace did not consider women in the movement like Francis M. Beal, who as a member of SNCC proposed a three-point plan to mitigate sexism within the movement, a plan which was later adopted as the organization’s official position. That is more than a valid question.

Also included in the Verso reissue of Black Macho is an introduction from Michele Wallace herself, written in 1990. In it she reviews her book and concludes that many of her arguments fall short. As Lemieux writes in her foreword, Wallace effectively “took herself to the woodshed” — admitting that the book would not pass her own standards for rigorous scholarship now.. Throughout the book, the reader is asked to make sweeping Manichean judgements which — while rhetorically powerful and deeply satisfying in their indelicacy — lack the evidentiary force of interviews or the movement archive. But then again, maybe Black Macho doesn’t need to justify itself in relation to a movement archive or even to contemporary critics. As a text, Black Macho has been so valuable over time because it operates more smoothly in a more intimate milieu — creating space between people in such a way that asks for a response — by posing pointed questions. The same way Ms. was unprepared to receive a young Michele Wallace for her cover shoot, many readers were resistant to the arguments of the book.

Today, the resistance to Black women’s anger takes the form of a racist backlash against the disruptors of a Seattle Bernie Sanders campaign event. We can understand Marissa Johnson and Mara Willaford as the living inheritors of Lorde’s call to anger in the contemporary Black Movement. The will to silence them is not new and like Wallace, the vitriol they have incurred comes seemingly from all sides of the political spectrum. In particular, Johnson and Willaford have been denounced for the manner of their critique — too angry, vitriolic — and for attacking a supposed ally in Sanders. Wallace, too, was lambasted for her angry message attacking a supposed ally in the Black man. Black Macho may have been inconvenient; it may not have been careful. But it was a necessary push forward. Getting angry works for Black women — it gets results and keeps us alive. And we haven’t stopped deploying it to save ourselves when America wants us either compliant or dead.