I’m writing to express my staunch solidarity with, and support for, the striking graduate student instructors, teaching assistants, and research assistants at Columbia University. As a former member of Columbia’s distinguished faculty, I am quite frankly appalled by the administration’s refusal to negotiate with the Graduate Workers of Columbia-United Auto Workers Local 2110. The explanation laid out in Provost John Coatsworth’s letter of April 18, 2018 is chock-full with anti-union clichés and tired scare tactics—unions threaten individual autonomy, exorbitant dues will be forced on those who did not choose union representation, contracts will place unnecessary constraints on academic units that do not conform to the traditional liberal arts classroom, the university already invests generously in each graduate student, ad infinitum. And then there is the administration’s mantra: “we believe it would not serve the best interests of our academic mission—or of students themselves—for our student teaching and research assistants to engage with the University as employees rather than students.” Why? Because treating grad students as workers deserving of fair wages and benefits, workplace protections, and dignity undermines the “special” (hierarchical) relationship between faculty and student.

Any reasonable person who has spent time in universities knows that what graduate teaching assistants and instructors do is paid labor. They organize their classrooms, interact with students in and out of class, grade papers, create assignments (in-class and out), spend hours on prep time that invariably has little or no relation to their actual primary research. The empirical evidence is beyond dispute. I was a member of New York University’s faculty when the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) under President Bill Clinton decided that our graduate students were, indeed, workers and had a right to unionize. When the NLRB reversed its decision under President George W. Bush, it was driven by an ideological opposition to unions and collective bargaining. This was no secret. That the NLRB sided with Columbia University students in 2016 should not surprise us, either, since the Obama administration recognized that workers’ right to organize had been protected at least since the New Deal, and graduate assistants were workers. But once again, the pendulum swings toward the Reagan-Thatcher vision of a world where there is “no such thing as society,” where solidarity undermines individual liberty, where “workers” are merely individual human capitals whose success depends on their competitive edge in a “free” and unregulated market. The Trump administration is transparent; it would prefer to eliminate the NLRB altogether.

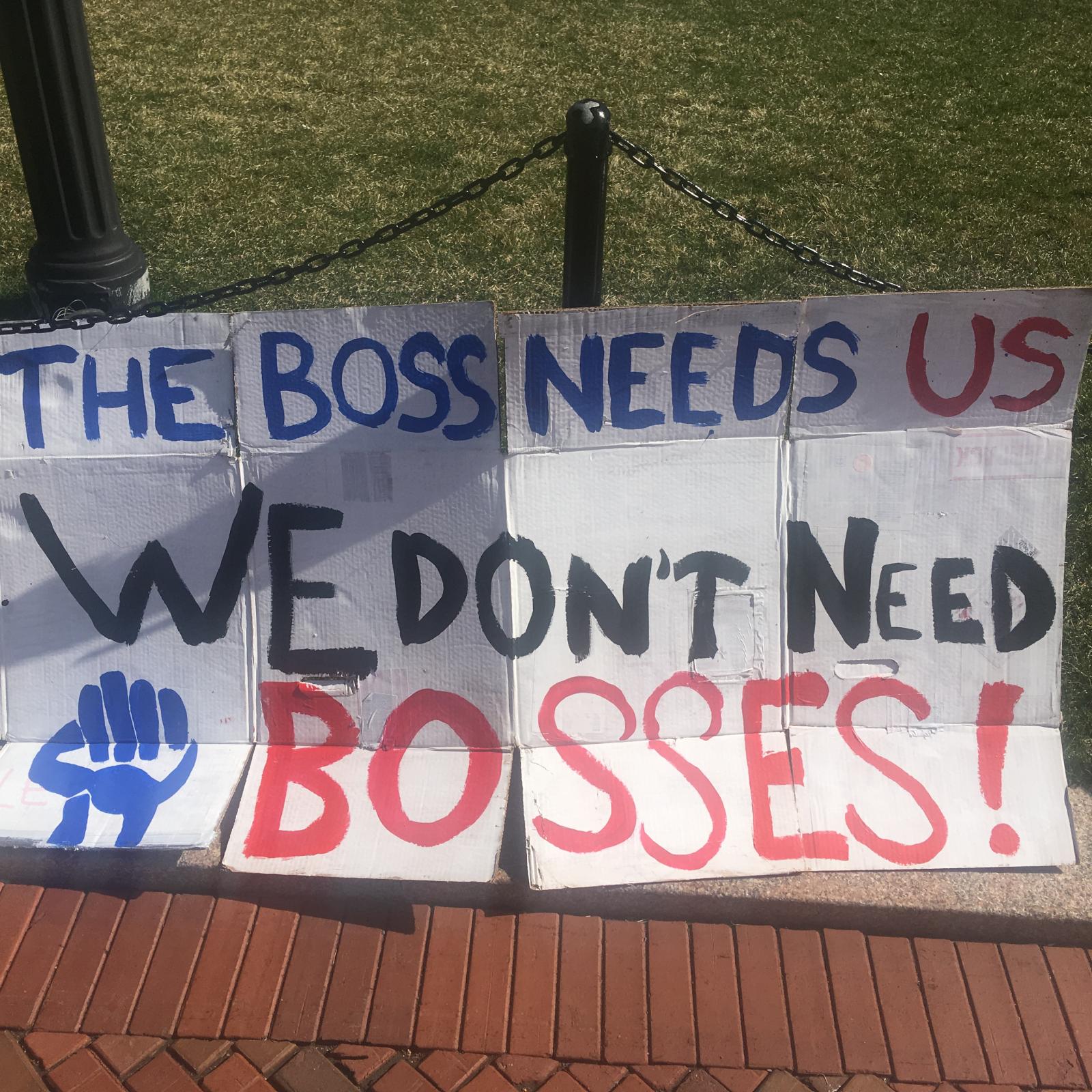

This is why I find Columbia University spokesperson Caroline Adelman’s statement on behalf of the administration not only disingenuous but offensive: “we do not understand why the G.W.C.-U.A.W. prefers the pressure tactics and disruption of a strike to a definitive, nonpartisan resolution of that legal question in the federal courts.” The university has used its power and resources to resist unionization. University administrators have spent millions litigating these cases and fighting unionization—often the costs exceed what the union is asking for. The graduate workers must use their power and resources to fight for recognition and cannot rely on what will clearly be a partisan resolution in the courts. And the power they possess is no different than the power Columbia students possessed fifty years ago when it shut down the university in defense of neighboring black and brown communities facing dispossession, Southeast Asia facing brutal war, and students who faced violence and retaliation for their principled stance.

In addition to my years at NYU and Columbia, I’ve also had the pleasure of working at universities with strong graduate student unions—notably, the University of Michigan and the University of California, Los Angeles, where I am currently on the faculty. I know from experience that a strong T. A. union actually improves teaching, faculty-graduate student interaction, and overall morale. Job security, health benefits, decent (though never great) wages, grievance procedures, anti-discrimination clauses, and clear guidelines as to workload and expectations, have ultimately led to a substantial improvement in teaching at the undergraduate level. These union-derived benefits have been instrumental for keeping more graduate students in their respective programs, thus contributing to the high completion rates at both institutions.

The long effort to organize graduate workers takes on a special urgency as academic labor becomes more and more precarious. These students are on the frontlines of a broader struggle against a new university order that entails the casualization of labor (teaching staff as well as the outsourcing of non-union labor in the realms of maintenance, food services, and security); rapidly increasing tuitions; investments in prisons, fossil fuel industries, and corporations whose business dealings buttress human rights violations; and the financialization of higher education resulting in unsustainable student debt and corporate profit. These students are fighting for a different future, a different university. And they are modeling that university even as they strike. They are working on their own time to make sure their students are prepared for finals and using the strike as a teachable moment to interrogate the relationship between universities and labor and pedagogy. Anyone who cares about the future of the university, let alone the country, ought to at least consider their vision of a university that cares about the well-being of everyone—students and staff. Their victory is essential if we are to begin to turn the tide.