Then he spent the rest of the night with her in embracing and clipping, plying the particle of copulation in concert and joining the conjunctive with the conjoined, whilst her husband was a cast-out nunnation of construction. —Arabian Nights, 1706

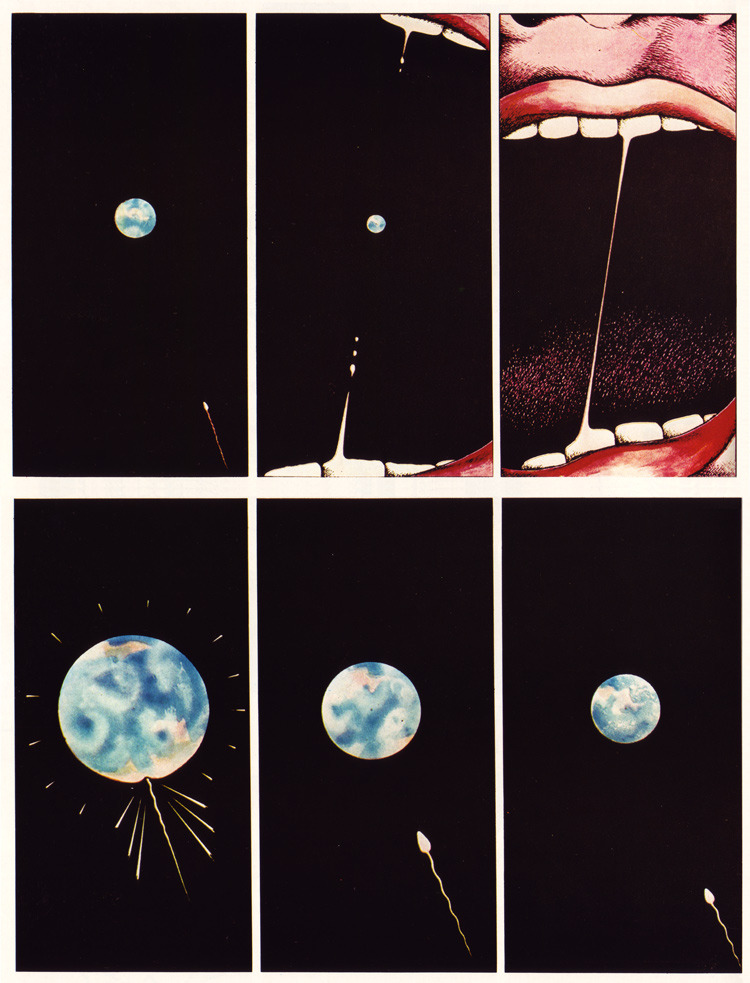

It follows that the collusion of grammar (of rhetoric or scholasticism) and the erotic is not only 'funny'; it marks out with precision and seriousness a transgressive site where two taboos are lifted: that of language and that of sex. —Roland Barthes, “The Old Rhetoric,” 1970

Get jiggy with my frontal lobes and it’s way more likely I’ll let you get jiggy with my lady globes. — comedian Emma Markezic in Cosmopolitan, 2011

The numbers that survive in my phone don't belong to those boys and men who were best at fucking me, but the ones who were, and are, best at telling me how—and why, and where, and also in which places—they would fuck me. I know where my priorities lie; here is where they tell the truth. Good sex is a miraculously dependent and alchemic performance, never with one author. It could take more than two, but never fewer. Good sexting, though, is an uncommon skill, almost concrete, not improved by lighting or blood alcohol content or desperate circumstances or any other measures. It is better in dialogue but doesn't have to be; it's a thing you can do to someone with literally nothing but their consent and attention. You can even keep your clothes on, if you're so inclined. This is what I mean about priorities. Good sex I can usually leave wherever I found it, but good sexters I keep forever in my pocket.

Those few talented contacts and I, we've made connections. There was a New York Times essay recently about how alone we are together. Maybe you read it, maybe not. But if you have parents, you can guess the gist: We have gained a thousand Twitter followers and lost our own souls; we've forgotten how to think before or while we speak; we're so busy texting all the time we never actually talk. As the writer said, as so many newspaper writers have said, we've sacrificed conversation for “mere connection.”

Most of us can remember a time before constant Internetting, and most of us have had, conservatively, a million IRL conversations, but all we remember are connections. The connection isn't mere. The connection—the electric feeling of “getting” somebody else in the relative simultaneity of them “getting” you—is the viscera, the elan vital of conversation. What matters isn't whether you're talking (out loud) or texting (into your phone), but what you have to say. The medium isn't the message. I don't entirely believe that, but I believe it a little more every day.

Privileging face-to-face conversation makes a virtue of proximity and reduces the wide world to a set of hyper-literal possibilities. It's so obsessed with the real that it's unrealistic, atavistic, and just silly. There is nothing like talking to somebody IRL, it's true. There is also nothing like body language or like the feeling of being looked at when you want to be. But when it's good there's really nothing like sexting.

Well, nothing that is, except for all the earlier and other instances of codifying desire in a future-perfect way, like erotic letter-writing, like sex-room chatting, like getting illicit with it on AIM.

Later, when we finally got the first slow Internet, I logged into chat rooms under names like Amber and Vanessa, pretending I was 18 and blonde and a model-slash-actress. There, with a little help from Literotica.com, I learned how to fuck. Education in the flesh came later still, but to this day, I'm more likely to read Literotica than watch RedTube. I would rather have Sade's “pornograms,” as Barthes called them, than the porniest Instagrams; “the erotic as a grammarian” leads me the most reliably to exclamation points. I can register words in my whole nerves. I can't always register touch.

Once I was so nearly anhedonic that not only was I unable to leave my friend's house where I was staying, but I also could not manage to turn the lights on and, most wretchedly of all, had my intern bring me coffee and the new Girls record, but was terrified to answer the door when she came. So I laid on the couch and got turned out over text with my sex-addict friend while exchanging filthy pictures with a writer I kind of hope never to meet. I could take pleasure over and over, from all of that, while not being able to look anyone in the eye.

An aside to the parents in the audience: This is why you do not need to worry so much about sexting. Lips don't always do as hands do. The thrill is liminal. And, at any age, thinking that all sexting will or should lead to sex is like believing all novels should be films.

The film inside your head, as any reader knows, is sometimes better.

Pop science continues to dictate that women get more word-feelings while men get more image-feelings, and as cringey as it is to agree with the kind of studies that inform pitches for NBC sitcoms, I also can't disagree. Men often think women like being told what to do in bed, and probably—I don't know; I'm not Katie Roiphe—many women do. But I think it's more likely that women, whose societally instilled role is still to “play hard to get,” just want to be talked to at all. “Seduction,” Baudrillard said and I remember, “is always more singular and sublime than sex and it commands the higher price.” Seduction is language, bodily or verbal, not action. It is ritual with sacrifice and challenge with or without goal, which is why it's easier to do well when the smartphone, not the object, is at hand.

Consider what's required in a formal sentence: the rhythm of punctuation, of course, but also knowing when to start, when to stop. Consider too the devastating effects of a well-timed ellipsis; read some Bataille. Erotic grammar is good grammar. Sexting has sped up seduction, but if you write it right, it can still torture.

I have a long-distance lover now and our text exchanges are fragmentary and agonizing and great. We met in person and had sex in person which helps fill in the ellipses, and I still always want to have sex in person, especially because we can't. But wanting is sometimes as close to ecstasy as having. I always think about the first time we were in some incalescent argument on g-chat and he finally said, “you're right,” and then (though he had yet to touch me) “for some reason that makes me want to slide my hand under your skirt up your thigh,” and then, “I'm going to go eat...” and then, “lunch.” And reader, I fucking died.

Meanwhile, so many face-to-face conversations with equally smart and good-looking males I only lived to forget.

It is funny how many of the traditional newspaper writers who castigate “my” generation's sexting as somehow stemming “real” flesh-and-blood desire are of a type with those who consume and exalt the penned exchanges of Henry Miller and Anais Nin, or of James Joyce and Nora. It is strange they don't see the smooth continuity. In some ways the speed and ease and volume of texts have devalued the content, but in others texting and IMing and g-chatting are improvisational evolutions of letter-writing, making it automatic and collaborative, not single-handed and static. Making it, in one word, hotter.