On Tumblr, users can look at art without even realizing it. Do they democratize the work or merely make it an advertisement for itself?

Last August, in the midst of controversy over populist exhibitions at MOCA in Los Angeles, museum director Jeffrey Deitch described a new sort of art audience: “They're not the people who make a living as artists, art critics or professional art collectors ... These are people who hear about a great new film they want to go to. They hear that there's a terrific new fashion store that's very cool — they want to go there. They don't differentiate between these cultural forms.” It follows that the blockbuster-exhibit-obsessed art world — like its not-so-distant cousin, Hollywood — must now compete with the onslaught of other entertainment forms and devices for the limited attention of such viewers.

Netflix, YouTube, Vimeo, Gawker, tablets, and mobile phones have all contributed to our daily retinal traffic jam, as art historian David Joselit argues in the waning pages of After Art. This, he argues, has forced geriatric museums to pop the institutional equivalent of Cialis and erect larger, more elaborate architectural additions to draw globe-trotting tourists into newly deindustrialized cities.

Absent from Joselit’s lament, though, is the fact that many artists thrive within these media forms that are believed to threaten traditional exhibition spaces. Contrary to oft-heard accounts of balkanization and walled gardens present in social networks, several recent art projects have exceeded the bounds of their original context, gaining a large non-art-related audience en route to online virality. These audiences share images and videos initially conceived as artworks without any concern for authorship, context, or property — without any particular awareness that they are engaging with “art” at all. That is, they are art audiences by accident.

What becomes of art when the majority of those interacting with it don't recognize it as such? What happens “after art”?

To examine the accidental audience in action, I will be focusing on Jogging — a blog I founded with Lauren Christiansen and presently contribute to, along with hundreds of others — because I have been able to track how a wide range of viewers have interacted with work posted there.

De-Authorship, Decontextualization, and Art as Property

Jogging began as a Tumblr in 2009 that displayed Google Image Searched products Photoshopped together as artworks, with the same text you’d find on any museum wall placard: title, date, medium, and author. Discrepancies would arise between the visual content and the descriptions, as digital collages were variously titled as installations, paintings, or sculptures, raising questions about the leveling effects of installation photography on all mediums and the power that documentary images have over the physical objects they depict. The site garnered a small amount of attention in its first two years, and then after a hiatus, its popularity grew exponentially with the inclusion of a dozen new members and a significantly increased posting schedule over the summer of 2012. As the project’s popularity increased, the work featured on it became increasingly, paradoxically, dissociated from the names of those who created it.

It’s fair to say Jogging faced this predicament because of Tumblr, the largest image-aggregating social network on the Internet, comprising 50 million blogs with 20 billion images last year alone. Every Tumblr post openly tracks its number of notes — the total of likes and reblogs a post receives. Among Tumblr users, reblogs — an automated form of appropriation that takes media from one blog and inserts it on your own — are the preferred note currency because they exponentially increase a post’s visibility and the likelihood it will be further circulated. When users reblog content in Tumblr, the service publicly keeps track of where posts originated and who has since liked or reblogged those posts.

Reblogs are simultaneously a form of viewership and a mode of display: they acknowledge a user's past interest as audience while offering content to future audiences. Reblogging thus has similarities to what sociologists call prosumption, the act of consuming and producing at the same time. For some, prosumption constitutes part of their artistic practice, though most typify this relationship with content as a way of curating.

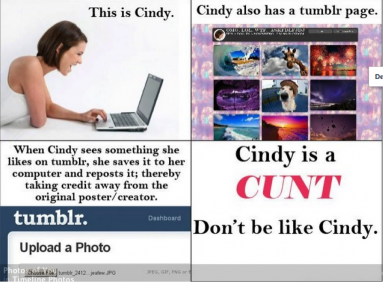

On a social network flush with recycled posts, there's a premium on delivering original content for others to share. Attention-hungry users gain prestige by being seen as the origin point of a highly sharable image. It isn’t as impressive if a post has 10,000 notes and you’re the 10,001st person to reblog it. This creates an incentive for users to drag popular images to their desktop and fraudulently repost them on Tumblr as though they had created or found the image independently. It's not a lie about creation but a lie about curation (“Look what I found,” not "Look what I made") to put one's taste and image-hunting abilities in the best possible light — to make them seem original.

By manually reposting and opting out of Tumblr’s provenance interface, users essentially cut off the author’s signature from a work. Such fraudulent reposting is as commonplace as it is despised, though it would seem the theft of authorship or curatorial taste is the logical conclusion of a social network premised on the appropriation of content. The majority of Tumblr’s viewership occurs through its Dashboard, where notes are always made visible, but notes and backlinks can be obscured by skins that prohibit visitors from viewing the number of notes of any given post on a user’s Tumblr homepage.

These omissions and obfuscations of authorship create an increased likelihood that art images will be stripped of their status as art, allowing audiences to understand the work as something other than art. They become accidental art audiences.

Much of the audience for art has always been to some degree accidental. Take, for instance, the Sunday tourist visiting a museum that happens to be showing a survey of contemporary art. As visual art’s focus has largely shifted from representation and craft to engage with art-historical discourse, it’s increasingly likely the average viewer may be wholly oblivious to what is being addressed, the artists featured, or their stated intentions without some level of a priori familiarity with the art world. For this viewer, it’s the museum rather than the art that has been sought out, and although artworks are assumed to be inside, any art for them will do.

The difference between the Sunday museum tourist and the Tumblr user who sees an 11th generation reblog of an anonymized art image is a matter of intentionality: Despite the Sunday tourists’ so-called lack of rigorous intellectual engagement with the contemporary art show, they did intend to see some kind of art, and the museum guaranteed for them that that was what they were doing. The Tumblr viewer who sees an art-image-gone-viral on his friend’s kawaii-themed Tumblr may not be in the pursuit of art at all. Instead he is pursuing relevant content in the broadest possible sense, looking to reblog images he wants to associate himself with, and "like" content he finds somewhat less interesting.

One way to conceptualize the accidental art audience’s relationship with context and property is through Joselit’s ideas of “image fundamentalism” and “image neoliberalism,” terms he borrows from political analysis to describe competing visions of where art must be located for its meaning to be authentically embodied. For the image fundamentalist, art’s meaning is inseparably tied to its place of origin through historic or religious significance; to remove this art from its home is to sever its ties with the context that grants the work its aura. For the image neoliberal, art is a universal cultural product that should be free to travel wherever the market or museums take it; meaning is created through a work's ability to reach the widest audience and not through any particular location at which it’s viewed. So when the Acropolis Museum in Athens demands the Elgin Parthenon Marbles be returned from the British Museum in London, proponents of image fundamentalism (Acropolis Museum) confront image neoliberalism (British Museum).

Image fundamentalists see the rights to property as being granted at birth through cultural or geographic specificity, while for neoliberals, art’s status as property is ensured through a work's ability to be sold, traded, or gifted like any other owned thing in a market economy.

The accidental audience’s attitude toward what it sees is deeply predicated on the neoliberal vision of cultural migration, but its willingness to strip images of their status as property is so aggressive that it deserves a term of its own: image anarchism. Whereas image fundamentalists and image neoliberals disagree over how art becomes property, image anarchists behave as though intellectual property is not property at all. While the image neoliberal still believes in the owner as the steward of globally migratory artworks, the image anarchist reflects a generational indifference toward intellectual property, regarding it as a bureaucratically regulated construct. This indifference stems from file sharing and extends to de-authored, decontextualized Tumblr posts. Image anarchism is the path that leads art to exist outside the context of art.

Art After Art

Art’s relationship with the new accidental audience and new quasi-exhibition spaces online is rife with awkwardness, mistaken presumptions, and anger. What else could be expected, given that these audiences don’t necessarily regard themselves as having anything to do with art? Joselit aptly describes the zeitgeist of contemporary artistic production, detailing “a broader shift in emphasis among contemporary artists from individual or discrete objects to the disruption or manipulation of populations of images through various methods of selecting and reframing existing content.” In other words, artists today are less interested in creating from scratch and more interested in tying together a variety of pre-existing references and materials. It makes sense that so much of today’s work looks eerily familiar in the way it mimics or appropriates wholesale from advertising strategies, mass-produced goods, and service-sector interpersonal exchanges. Context remains the final stopgap separating art from the subject of its appropriation, though in general, art remains more distant from the things it appropriates than artists tend to think.

Compared with the “real” products of the world — mass-produced goods with professional sheen, ubiquitous commercial presence, and celebrity endorsements — artworks generally look and exist in some way other. Those without an art education have nonetheless become keenly trained visual analysts by way of viewing a daily onslaught of well-designed advertisements. Images that began as art but have reached a level of widespread popularity beyond that context are thus judged according to that training and the visual vocabulary of advertising, where vague similarities are found through the mutual use of commercial goods and techniques. The art image becomes an awkward curiosity for the accidental audience, landing in an uncanny valley of familiarity and otherness.

Based on my experience of closely following the ebb and flow of Jogging’s most recent 2000 posts, I can classify accidental-audience reactions to decontextualized art into three main categories:

1. WTF I don’t even?

This is the accidental audience’s most common response. “WTF I don’t even?” is a textual meme for the bafflement experienced when one comes in contact with far-off corners of the internet. It's reserved for the rare examples of things that fall outside any known trajectory, despite all the visual training and pattern finding internet viewers have learned to perform as they parse through their RSS feeds.

While this might seem a negative judgment of the art, it’s important to remember the accidental audience doesn’t think it’s art in the first place. For them, these images are not bad art so much as the epitome of randomness. The giddy confusion they express at decontextualized art is less an assertion about the art and more like a search query or cry for assistance: “What am I looking it?” “Where does it belong?"*

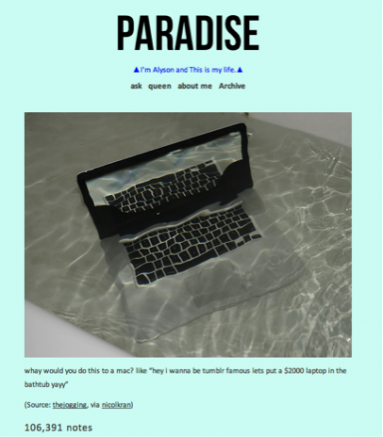

Take Will Shea and Shawn C. Smith’s Jogging post Mac Bath, 2013 for example, an image that accumulated over 100,000 notes in the span of a month. Mac Bath features a tightly cropped image of a Macbook Pro almost fully engulfed in the water of a running bathtub. Some rebloggers encountering the image without context saw its as documenting an unfortunate mistake but were skeptical of why the image’s creator chose to photograph the computer rather than save it. Viewers would later cite the image’s popularity as a motive for its creation, offering commentary like, “$2000 down the drain all to become Tumblr famous. Was it worth it?” or “Only white people would do this for notes.”

The accidental audience knew there was something odd going on in this image, but the anonymized trail of Tumblr left behind few, if any, clues to what its original purpose was. The search for context on Tumblr is often a catch-22: In order to look for the original, you must first make a copy by reblogging and asking for help. In the case of Mac Bath, the enormous number of perplexed copies came to supplant the intention behind the production of the original.

2. You’re doing it wrong.

Not all of the accidental audience meets images of art with perplexity or suspicion. Many take the appropriated products and materials used by artists at face value, believing their depicted use to be the sincere and mistaken work of a fool.

The textual meme “You’re doing it wrong” has sprung from a zealousness to point out the laziness or irrationality of others’ purposely shared attempts at cooking, transportation, romance, and all else. It marks a dual sincerity: The accidental viewer sincerely believes the art image to be the sincere documentation of a poor attempt at functionality. The beauty in this misunderstanding is that, on the level of the image, when the accidental audience recirculates it, it fulfills the avant-garde ambition for art to be integrated with everyday life — only now achieved through a kaleidoscopic twist in context. The flow of art back into everyday life through Tumblr marks a security flaw in what is often described as the “hermetically sealed” art world.

The levee between art and life is becoming increasingly strained through rampant appropriation. This transformation (or context-deprived misreading) is not adding new meaning to the work but returning it to its original context — a return to an understanding based on functionality rather than aesthetics.

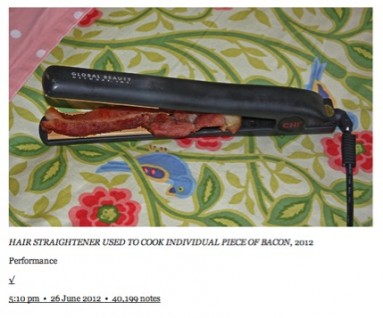

A direct example of art’s disintegration back into the source of its own appropriation can be found in the story of Aaron Graham’s Jogging post HAIR STRAIGHTENER USED TO COOK INDIVIDUAL PIECE OF BACON, 2012, an image that has amassed 40,000 notes on Tumblr and leaked into other social media networks. Graham draws inspiration from amateur sites that feature “kludges,” inelegantly jerry-rigged combinations of everyday objects. The more preposterous and unexpected the combination, the more popular the kludge generally becomes. A week after posting the image on Jogging, HAIR STRAIGHTENER USED TO COOK INDIVIDUAL PIECE OF BACON accumulated an accidental audience very quickly, and the image was anonymously reposted without attribution to the curated kludge site ThereIFixedIt.com, which even put its own watermark on the image.

Graham’s sculpture simultaneously evokes the high-art Dadaist tradition of assemblage as well as the pop culturally indebted kludges, making the inclusion of his sculpture on Jogging and then accidentally on the popular kludge website ThereIFixedIt.com apropos — it successfully merged both visual vocabularies. The full circle that Graham’s sculpture has traveled marks the power of the literal-minded accidental audience as a connector and creator of image meanings. You can already hear the sound of the accidental audience attempting to pee in Duchamp’s Fountain while a chorus of others photographs them, remarking on that toilet’s lack of plumbing.

3. My kid could do that!

Jogging includes on all posts abstract symbols as links back to creators’ websites. For most, these symbols are unobtrusive nonsense that goes unnoticed far more easily than a fully articulated authorial signature with a first and last name would. In this way Jogging encourages the disregard of authorship while allowing those who are curious about a creator a ubiquitous, if minor, point of entry.

Some of those from Camp A (WTF I don’t even?) are able to catch Jogging posts before they go viral to the extent that all textual description has been lost, which allows them to discover the portfolio of the artist. When this reveals a post as a work of fine art, it pushes portions of the accidental audience into a fit of outrage at the work’s pretension, eliciting many variations of the classic critique, “My kid could do that.” Ironically, this outrage often propels hundreds if not thousands more notes to rack up, as one incredulous viewer after another reblogs the image from earlier rebloggers, building a chorus of angry hysteria.

That a so-called bad post would become popular isn’t unusual — many absurd, poorly crafted, and perhaps immoral posts accrue huge popularity on Tumblr all the time. Instead, this outrage reflects how the collision of low-culture absurdity and high-culture art reveals the material deskilling of artists, which makes accidental audiences question art itself.

Of course, it’s true: Most children can produce works of art that would be published on Jogging. But that’s not the point. No one better explains the paradox of an audience who expresses anger (rather than seeing opportunity) that something they could have created became a successful work of art than Boris Groys in his essay The Weak Universalism:

Avant-garde art today remains unpopular by default, even when exhibited in major museums. Paradoxically, it is generally seen as a non-democratic, elitist art not because it is perceived as a strong art, but because it is perceived as a weak art. Which is to say that the avant-garde is rejected—or, rather, overlooked—by wider, democratic audiences precisely for being a democratic art; the avant-garde is not popular because it is democratic. And if the avant-garde were popular, it would be non-democratic. Indeed, the avant-garde opens a way for an average person to understand himself or herself as an artist—to enter the field of art as a producer of weak, poor, only partially visible images. But an average person is by definition not popular—only stars, celebrities, and exceptional and famous personalities can be popular. Popular art is made for a population consisting of spectators. Avant-garde art is made for a population consisting of artists.

This paragraph, when applied not to museum attendees but to Tumblr’s accidental audience, cuts to the heart of the general uncertainty over whether the ongoing appropriation of others’ work through social media constitutes a form of production. In other words, Would the accidental audience describe themselves as viewers and/or creators of culture in general? Prosumer seems the most accurate.

For artists using social media like Tumblr, the question is not whether their involvement constitutes an act of curation or artistic production, but whether the specificity of those aims (curating, art making) are tenable according to their present definitions when placed in front of audiences who hold such wide ranging motivations for their own spectatorship. At what point do artists using social media stop making art for the idealized art world audience they want and start embracing the new audience they have?

To a certain extent, Jogging has attempted to do this by downplaying authorship, maintaining a post rate for original content that's as fast as other Tumblrs' image-reblogging, and producing works that draw inspiration from general Web content. Jogging is not the first to do this, and surely more efforts to artistically capitalize on the unbalkanized attention economy of the Internet will follow.

The accidental audience’s schizophrenia of occupying both positions of viewer and creator simultaneously is directly embodied in reblogging, which acknowledges one’s role as a past-tense spectator while allowing for the future-tense spectatorship of others. Out of this simultaneity comes a third option the breaks apart Groys’s dichotomy of unpopular democratic art vs. popular undemocratic art: popular art that is also democratic. The accidental audience’s scale and effectiveness in dissemination for democratic work proves this option is possible — just don’t tell anyone it’s art once the images get out there. For all I know, they might be something else at that point.