At 14, I ate whatever I wanted, dreamed of going to university on scholarship, and was being scouted by a few Ivy Leagues for what promised to be a decent college running career. By 18, moving made me dizzy, most foods made me sick, I was shitting blood every day, and I was banned from three different local pharmacies because they knew what I was doing with the Ipecac I claimed was for my mom’s first-aid kit. Though I started high school golden healthy, I went off to debtor’s college (no athletic scholarships for me) with a host of physical and mental illnesses, including clinical depression, bulimia, and ulcerative colitis, an autoimmune disease that runs in my family.

Nobody who saw me then could doubt that something was wrong—lightless skin, dead hair, body too thin or bloated from the uniquely hot hell of a binge/purge cycle while unable to digest anything—but other than a nurse practitioner prescribing me some psychiatric drugs, not much was done. My mom thought getting better was a matter of willpower; my dad recommended prayer.

Years later, when I was in remission for my colitis and in treatment for my mental illnesses (made possible through spotty insurance, trial and error, and luck), I had to track down my old medical records, which I’d never seen before, for a new specialist. A summary of my teenage medical history was stapled to the top, typed and signed by the Nurse Practitioner, a grandmotherly woman I had always trusted. This is what it said:

“[Deadname redacted] is a normal, healthy teenage girl who experiences some anxiety.”

Had I read the NP’s summary back when I was a teenager, I would have believed it: I was well-trained in the discipline of not mattering. Reading it as an adult well on their way to self-actualization, however, I was overcome with white-hot fucking fury. It had taken me years of therapy to recognize my anger, an emotion I was raised to believe girls couldn’t have. It turned out that anger was another word for the liquid fire under my skin, which only went away when I cut myself or ran ten miles or threw up until I couldn’t anymore. Even now, that fury returns when I recall the callousness of a medical professional who saw a dissociative, anemic, malnourished, blood-shitting teenage zombie and decided that their diagnoses and symptoms were not just negligible but not happening, nightmare filaments to be swept away like cobwebs from a corner.

I’m far from the first chronically ill person whose sickness has been underestimated or even denied by those who were supposed to help, and with both chronic illness in general and autoimmune disease in particular on the rise in the United States, such experiences will only become more common. Chronic illnesses like heart disease, cancer, and diabetes are the leading causes of death and disability in the States, and among the most expensive health concerns to treat—90% of annual health care expenditures go toward people with chronic physical and mental health conditions. Unsurprisingly, medical bills are the number-one cause of bankruptcy filings. In a country where 28 million of us don’t have insurance, where crowdfunding for life-saving medical care has become routine, and where many will simply die because they can’t afford treatment hoarded and capitalized on by private pharmaceutical and insurance companies, disregard for pain and sickness, especially for those who aren’t white cis men, is a systemic reality.

Like chronic illness, autoimmune diseases are becoming more common, more expensive to treat, and more frequently comorbid with other diseases, but the attention and resources devoted to treating them are significantly less and fewer than those provided for other chronic illnesses, like cancer. Autoimmune diseases take longer to diagnose—three years on average—in part because of their ability to affect multiple systems within the body, but also because it’s hard to diagnose a disease when its symptoms are ignored and the victim is discounted. No amount of money can secure you the credibility or access of a straight cis man or a white person, the people more often acknowledged as having “real” or non-stigmatized illnesses.

It took seven years to find treatment that put me in (an always conditional) remission. I was diagnosed relatively quickly, but many of my doctors, when I could afford them, still behaved as if my symptoms either weren’t happening or weren’t serious enough to merit attention. As a queer and trans person as well as a sick person, I’m accustomed to struggling for access to competent medical care, but after all these years, a doctor’s refusal to recognize my illnesses as illness still infuriates me. Every time is like the first time, a scalding reminder of my formative encounters with the medical industrial complex.

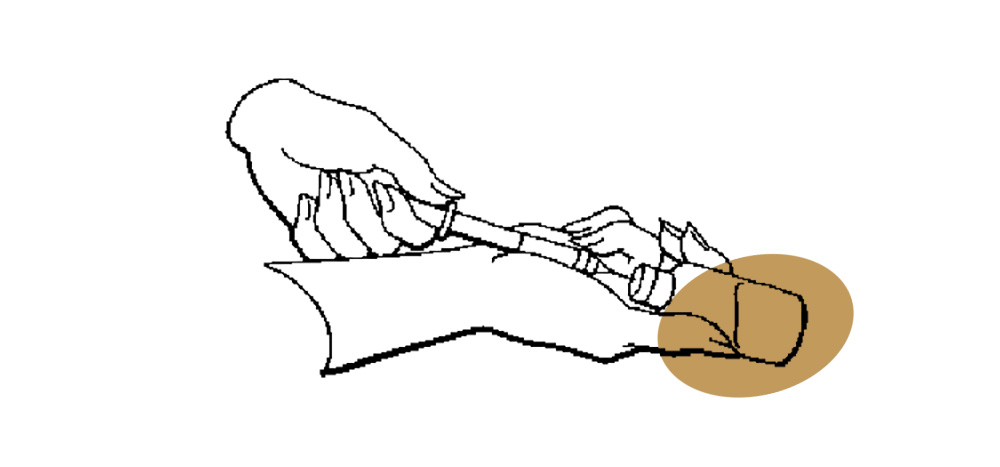

Dismissal is the first health care experience Caren Beilin writes about in Blackfishing the IUD, her memoir about her own autoimmune disease, rheumatoid arthritis (RA), which she says developed after she had the copper intrauterine device (IUD) implanted in her uterus in 2015. Only days after the procedure, her feet and hands swelled to twice their size, causing intense, disabling pain. When she went to a rheumatologist for answers, he hardly spared her a glance. “Men on the street have given me more thorough eyes than this one,” Beilin recalls.

Over the following months, Beilin took a barrage of tests, but through some oversight was not given the one designed to detect autoantibodies related to RA, despite her almost textbook symptoms. When she went to her primary care physician for more tests, he was just as dismissive as the specialist. “He shook his laughing head,” she reports. “‘Don’t be upset,’” he tells her. “‘I doubt it’s anything.’”

As it staggers toward its punchline, the joke of Beilin’s pain only becomes more absurd. She must fight to have her IUD removed (“What a waste,” chides one doctor, a woman this time), get diagnosed, and manage the labyrinth of administrative obstacles between her and healing, all on the salary of a bookstore employee. Weaving her own war of medical attrition with histories of and musings on the IUD, RA, autoimmune disease, women’s pain, modern art, witches, and the gendering of pretty much everything, Beilin’s dreamy, episodic, syntactically strange book is more poetic than what I’ve come to expect a chronic illness memoir to be—like a Bluets for suffering.

What it has in common with other memoirs of its kind, however, is at the core of the perpetual sickbed. As Lidija Haas wrote of Porochista Khakpour’s also-unconventional chronic illness memoir, Sick, Blackfishing “resists the clean narrative lines of many illness memoirs—in which order gives way to chaos, which is then resolved, with lessons learned and pain transcended along the way.” Any meditation on the experience of chronic illness necessarily concerns life and death, but to position death as life’s direct outcome is to treat a gravestone like a biography. My chronic illness puts me at much greater risk for certain cancers than the general population, but I will probably have to endure and manage the illness before it brings those cancers to pass: That my chronic illness will likely be a factor in my death doesn’t mean it isn’t also my lifestyle. As Audre Lorde wrote in The Cancer Journals, her 14-year struggle with breast cancer forced her to “[face] death as a life process.”

Like many people, Beilin got the IUD because she wanted to have sex without getting pregnant. “Skin on skin, a natural fucking, is a coveted closeness,” she writes. The implant is ostensibly a simple solution to an understandable desire (a solution whose popularity spiked after the abortion rights panic directly following the 2016 election). After she gets sick and begins learning about the IUD and what it does—or might do—to the body, she lists the common-sense reasons for not having gotten it in the first place, rebuking herself and her health care providers for not taking greater care; at one point, she excoriates Planned Parenthood for what she sees as its uncritical promotion of a device that isn’t as safe as it’s marketed to be. “Now we are awesome cyborgian women, feminists with metal we enjoy in our womb,” she scoffs. But no matter where she attributes blame, Beilin still must grapple with the conviction that in making what she was led to believe was the most responsible choice, she was forced to betray herself.

Like Lorde and Khakpour, Beilin has written in the tradition of the sick woman memoir. Like their books, hers is angry—at violent medical systems, at unsympathetic friends, acquaintances, and family, at her own body—with ferocity that shimmers on the page. Unlike other sick woman memoirs that I’ve come across, however, Blackfishing opens with a vendetta.

“I want to blackfish the IUD,” Beilin writes, referring to the 2013 documentary, Blackfish, whose popularity almost single-handedly destroyed SeaWorld’s business model by illuminating the abuses it inflicted on the marine animals it showcased. Her book begins with the announcement that she will destroy the object that she believes triggered her life-altering disease: She "aims to go blackfishing" to "make it impossible for the IUD to exist."

Not even Blackfish director Gabriela Cowperthwaite could have guessed the impact her film was to have. One of many parents to take her children to the theme park, she was inspired to make her documentary after a SeaWorld employee was killed by an orca in 2010, thinking “maybe I could pull back the curtain for the general public.” Blackfishing, which joins a long tradition of exposé, was an exercise in truth-telling, but the book it inspired is a different creature: Like a weapon, it has a target.

As

a genre, the sick woman memoir is indictment enough without reckoning for the women on whose bodies Western medicine was built, often without even the pretense of consent. The history of women of color, poor women, disabled women, indigenous women, incarcerated women, queer women, and people of other marginalized genders who have been used, farmed, tricked, and coerced into becoming test subjects for medical progress is long and terrifying. From gynecological experimentation on enslaved Black women to early oral contraceptive trials done on poor Puerto Rican women who were lied to about the experimental nature, and possible danger, of the drugs they were taking, the historical context of the sick woman memoir is littered with lies, suffering, and unnamed dead.

Writers who are concerned with sickness, especially those of us who are white, must engage with the ways that white supremacy intersects with gendered oppression and the dehumanization of sick and disabled people, not only because the failure to do so is a reproduction of the violence we purport to challenge, but because these things are inextricable from each other. If the chronic illness memoir challenges what it means to be sick, the sick woman memoir, in addressing the dehumanization of women, should challenge what it means to be human. This requires a sense of justice and imagination, both things that any writer worth their salt should strive to cultivate.

As it’s now commodified, however, the writerly concern with sickness has become a quest for “awareness.” As we learned from the personal essay boom of the aughts, the stories of sick writers are meant to fulfill some kind of social responsibility: the ambiguously defined “awareness” that’s measured in dollars for stockholders rather than accessible treatments and cures. Rather than being received as works of art, personal expression, or witness, first-person accounts of sick writers must evangelize for the greater good, which is to say, turn a profit for the corporations capitalizing on sickness itself. Pushback against the “awareness” mandate from authors in the sick woman genre like Khakpour,Esmé Weijun Wang, and Anne Elizabeth Moore not only dismantle “health” (and its tether, “wellness”), but also critique the consumerist appropriation of the narratives by which it’s been devoured.

But even if the new nonfiction about chronic autoimmune and mental illness is better equipped to resist assimilation into what might be called wellness writing, it cannot take on our country’s intensifying health care problem, or the intersectional human rights violations with which it’s intertwined. There are perhaps financial and pedagogical effects to consuming the memoir, supporting the author and informing the reader—but does this transaction create political actors? There is a difference between consumption and absorption, as anyone with a digestive disorder can attest.

This isn’t to say that naming disparities in health care access is meaningless. The exercise is not only foundational to consciousness-raising, but contributes to harm-reduction and even healing: Blackfishing is interspersed with devastating letters and Facebook messages to Beilin from women relaying the stories of what they believe is IUD-triggered RA, many of which include guidance for those considering the IUD or who may be experiencing health problems because of it.

Nevertheless, treatment for serious chronic illness almost always requires access to formal medical institutions, which in the States is a matter of cold, hard cash that also happens to be mediated by other systems of power. Autoimmune diseases primarily affect women almost across the board, and some, like lupus, are more likely to affect women of color in particular. As a teenage girl, my gender put me at a higher risk for autoimmune disease and made it harder to be taken seriously once I became sick, but this was heavily mitigated by my whiteness. Later, living as a dyke and then as a transsexual exposed me to further medical marginalization.

Investigating the power structures that oppress us also makes room for an understanding of the ones that don’t. Though it would be absurd to expect memoirists to write about experiences that aren’t their own, and unfair to demand they account for all of the world’s injustices, I do think Beilin’s very binary meditations on gender and misogyny are one of Blackfish’s main shortcomings. If the existence of trans or nonbinary people is ever explicitly referred to, then I missed it, an absence compounded by her tendency to collapse gender and gender performance. Indeed, in condensing thought processes to minds that are either “masculine” or “feminine,” Beilin makes the very type of “linear, little” mistakes that she attributes to the “masculine mind.” Being a gender that is not even considered in a text written in large part to address the violence of gendered marginalization is, if nothing else, a reminder of the fractal nature of gendered (and other identity-based) violence. As trans and non-binary people—and more broadly as people forgotten by or forbidden from the mainstream—we seek healing not only through violent institutions, but in violent counter-narratives, ones in which we may not even find ourselves.

There’s

an infamous two-episode special of The Golden Girls called “Sick and Tired,” where a prick doctor (played by that prick actor Jeffrey Tambor) tells Dorothy that although she has come to him for help with debilitating symptoms of exhaustion and pain, there is nothing wrong with her. It’s only after months of searching for a health care provider to take her seriously that she is finally diagnosed with chronic fatigue syndrome (these days known as ME/CFS). When she and the Girls go out to dinner to celebrate, the prick doctor just so happens to be at the restaurant. Dorothy, true to form, gives him a homespun yet elegant piece of her mind, inspiring the woman he’s eating with to join in on the chorus of righteous shaming raining down on his prick head. The episode was inspired by show creator Susan Harris’ own experiences with undiagnosed and dismissed autoimmune illness.

One need not have shared that experience to enjoy the triumph and excitement of that prick doctor’s comeuppance, but it certainly helps the schadenfreude sing. For many sick people, especially women and people of marginalized genders, being believed starts to feel like a miracle, one earned through the heartbreaking work of convincing others that your illness exists in the first place.

Dorothy’s anger is an inspiration to everyone who’s ever been dehumanized by a powerful white man, and as a depiction of feminist self-advocacy in American pop culture, years ahead of its time, but it also takes place in the white, middle-class fantasy of the show’s Reagan-era Miami, where the satisfaction of a verbal evisceration is its own politics. For every episode where a gay person comes out to acceptance or a wheelchair user is treated with respect, there’s another where Dorothy talks a teenage Mario Lopez into deporting himself because he didn’t immigrate “the right way.”

Like memes gloating over Nancy Pelosi’s performative sarcasm, or the disturbing personality cult/marketing gimmick surrounding one woman on our country’s most powerful nine-way appointed-for-life judicial body, Dorothy’s speech exists in a world where reaction amounts to resistance, affect to effect. Instead of contextualizing Dorothy’s anger as a valid emotion, The Golden Girls frames it as action, as befits the show’s formula of conflict > shenanigans > speech > resolution > credits. It’s not Dorothy Zbornak’s responsibility, nor is it within her individual power, to fix misogyny, or ageism, or the medical industrial complex—but it is the neoliberal project to convince consumers like her (always consumers, never patients) that it’s just the bad apple Jeffrey Tambors who are the problem.

The most interesting thing about Blackfishing the IUD is its essential gesture toward a militancy beyond anger. I don’t mean to position “mere” anger against action, but rather am distinguishing between emotion and political purpose. The militant or insurgent sick person is not new. In the States, radical sick and disabled activism has been happening around HIV/AIDS, the ADA, and self-determination since the disability rights movement as we now know it coalesced in the 1960s. But Beilin’s invocation of explicit and cooperative resistance feels original, at least in form. In the internet age of #MeToo and Black women sharing tactics to survive medical contexts in which Black mothers die at a rate that’s 3.3 times higher than white mothers, Blackfishing attempts an intentionally collective-minded response to the attacks on accessible health care, bodily autonomy, and reproductive access that have violated and harmed the rights of the sick.

In 2014, I attended Sick Fest in Oakland, where I was electrified by the convergence of sick and disabled anarchists and leftists at an event organized by sick and disabled people (including Amy Berkowitz, author of the excellent Tender Points, a sick woman memoir about fibromyalgia). Our collective presence, as well as the knowledge that despite accessibility measures many of us would still be unable to physically attend, was its own response to the event’s tagline: “How do you throw a brick through the window of a bank if you can't get out of bed?"

In the sense that it was an expression of anger about ableism, Sick Fest wasn’t all that different from Dorothy’s restaurant speech; but in the sense that it was also about expressing solidarity, strategizing for access, sharing art, and building community, it was effective in a way that her speech could never be. One saw anger as an endpoint, while the other demanded the manifestation of its political potential. In its best moments, the struggle against our training to deny our anger, or worse, to allow it to be subsumed by hollow, profit-driven narratives like “awareness,” is where Blackfishing lives.