A vibrant vision of radically inclusive blackness resolves when movement leaders imagine freedom and autonomy for black people of all marginalized identities and not just for themselves

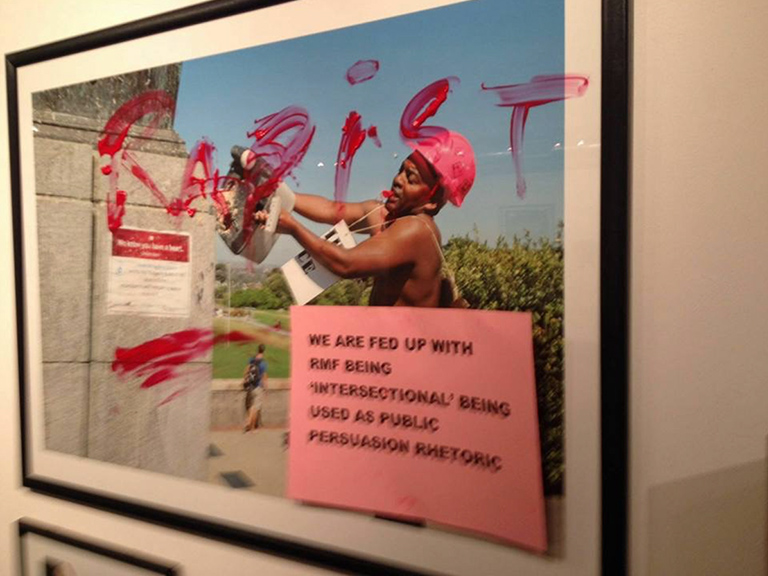

ON March 10 of this year, a photo exhibition staged by the University of Cape Town’s Rhodes Must Fall student movement underwent some surprise alterations. Paint was smeared on the subjects depicted, who were all members of the movement. The disruption came in response to the fact that for a year certain members had deliberately excluded and antagonized transgender, genderqueer, and nonbinary fellow members. Organized as the Trans Collective, an autonomous group, these latter members made critical contributions to campus movement politics, calling for the elimination of violent colonial, patriarchal, and white supremacist practices from the institution. Yet for their effort they received little recognition or respect. A mere three of the one hundred images featured in the exhibition were those of trans individuals.

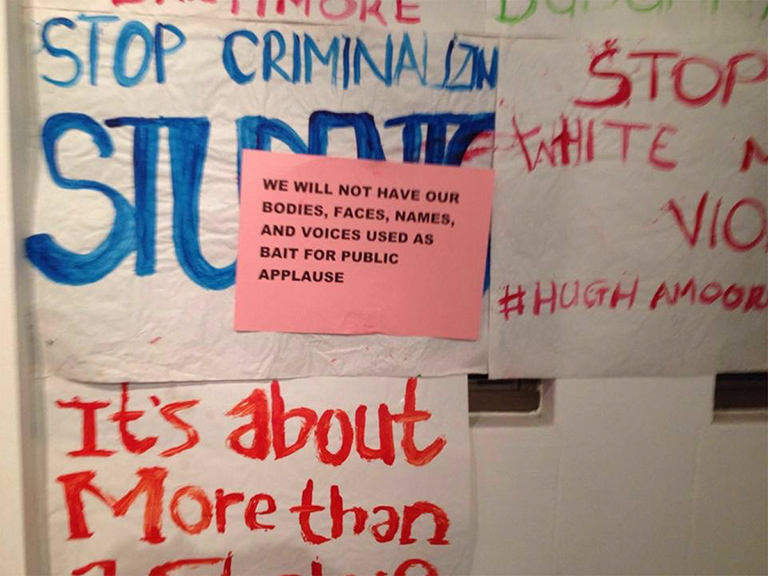

In addition to altering the exhibition in protest, the Trans Collective issued a statement: “It is disingenuous to include trans people in a public gallery when you have made no effort to include them in the private,” it read.

It is a lie to include trans people when the world is watching, but to erase and antagonize them when the world no longer cares.… We will not have our bodies, faces, names, and voices used as bait for public applause. We are tired of being expected to put our bodies on the line for people who refuse to do the same for us.

Critical regard of the theft of land means little if it is unaccompanied in black consciousness by critical regard of what discourses of gender and race do to black bodies. A black body politic may eagerly gobble up contributions by trans comrades while still failing to protect, affirm, acknowledge, and humanize them. Even a movement anchored and led by women—such as the celebrated imbokodo (Zulu for “rock” or “foundation”), which was immortalized by the hashtag #ImbokodoLead—often fails to acknowledge that transgender women are deliberately denied access to womanhood. Cisgender black women may demand a voice in a movement even as they silence black transgender women who also wish to speak. Casting off the shackles of colonized black identities may prove impossible if the effort has behind it no acknowledgement of the fact that a gender binary renders nonbinary and genderqueer black individuals functionally nonexistent.

Black revolutionary energies in the past have deliberately excluded and discriminated against cisgender women as well as queer and transgender individuals. And, sadly, they continue to do so. Community solidarity is presumed to be the exclusive province of cisgender, heterosexual black men because narratives around various forms of state violence tend to be gendered male.

When a black man is murdered by the state, the community takes to the street to mourn him. When the same state violence touches the lives of women, the community takes out handkerchiefs to grieve and sympathize with them for the loss of their men. Women whose end is the same as male victims are met with silence rather than reciprocal support. Carceral structures collapse the vast spectrum of black gendered and sexual identities to the status of criminal on the basis of the widely held assumption that it simply could not be otherwise. This criminalizing tendency affects queer and trans black individuals differently that it does cisgender heterosexual men. Non-normative gendered and sexualized bodies are not only criminal on the basis of blackness; they are also deemed wrong-bodied and deviant.

Tanisha Anderson, Rekia Boyd, Miriam Carey, Michelle Cusseaux, Shelly Frey, Kayla Moore, Yvette Smith, Yuvette Henderson, Darnisha Harris, Malissa Williams, Aiyana Stanley-Jones (a child), Tarika Wilson—the Twitter hashtag #SayHerName brought these names and others to the fore. They belong to black women and girls who, like many men before and after them, had all been killed in encounters with the police. Though the act of saying their names may appear to threaten and undermine black male dominance, it is not meant to. The names neither compete nor attempt to overshadow; they serve simply to offer a fuller picture of a community’s ongoing destruction.

A fuller picture still would be gained from saying the names Papi Edwards, Lamia Beard, Ty Underwood, Penny Proud, London Chanel, Jasmine Collins, India Clarke, Shade Schuler, Amber Monroe, Kandis Capri, Elisha Walker, Keisha Jenkins, and Zella Ziona. These belonged to trans individuals whose deaths went relatively unnoticed and unacknowledged due to the indifference to trans issues and active oppression of black trans women that characterizes a black liberation politics organized around cisgender identities. One might ask whether many popular conceptions of justice account for intracommunal gendered violence, and whether a “justice or else!” ultimatum accounts for the frustration of women unable to cope with black patriarchal structures and conventions as well as physical violence visited on them at the hands of black men.

Any collective understanding of blackness that excludes compounding identities is a violent mythology; it holds that blacks are discriminated against solely on the basis of skin color. Yet black feminist and womanist forebears have demonstrated that in determinations of blackness the violence stemming from gender and class plays a role as well. The result is what prominent black feminist Patricia Hill-Collins has termed “interlocking systems of oppression.”

Race, gender, class, and physical ability have become inextricably linked in understanding blackness and systemic oppression. Structures of whiteness certainly pre-date black chattel slavery in the United States. Nonetheless, this institution most clearly illustrates the ways in which black bodies came to be treated as commodities on the basis of methodically constructed difference. The perception was that blackness is universally subordinate to whiteness. Yet it obscured the fact that black men and women occupied different positions within slave economies on account of gender. As a result of the distinction, women endured greater sexual violence than men. They were forced to bear children, serve as wet nurses, endure sexual assault and bondage, and suffer other horrors.

Understanding the oppressive systems navigated by black people requires imagining resistance to whiteness as resistance to kyriarchy, an order predicated on interlinked modes of domination and submission. It requires recognition of the fact that black marginality stems from notions of black bodies as labor and capital. Though black men and women were both, only the bodies of cisgender women could produce new labor and capital. And they were valued for this ability. The legacy of this particularly notable form of commodification endures to the present day: black trans women are valued less because, among other reasons, they fail to adhere to essentialist conceptions of black womanhood. Of this, both white hegemony and reactionary cisnormative, queerphobic black patriarchy are guilty. A similar attitude affects queer black women; their non-normative desires and expressions, when articulated, fail to conform to particular gazes, and they are punished and corrected accordingly.

Though slave masters of the past objectified and violated black women, many present-day reactionary black patriarchs are keeping a spirit of that violence alive by romanticizing the ideal of the black “womb-man” whose sole function and duty is to mother new members of the race. For this reason alone, a masculinist politics that aspires to becoming the equivalent of an overthrown white male domination and whose fragility destroys cis and trans womanhood is as unrealistic a means of black women’s liberation as any attempt by black women to achieve equity with white women. A sexual politics that contests essentialist characterizations of bodies is necessary to liberate cis heterosexual women, cis queer women, transgender women of all sexualities, nonbinary individuals, and all possible combinations of black gender and sexuality.

Salvation lies in a black liberation politics organized around a conception of blackness that displaces cisgender heterosexual masculinity and places queer, transgender, disabled, poor, and other marginal black identities at the center. It promises to free men from the violent and hegemonic masculinities they have internalized as the most valid. It promises to inspire a collective vision of blackness free of white sexual and gender norms, one that unleashes the vibrant and dynamic potential that has always existed but has always been violently suppressed from outside of the community and policed from within.

It will be a participatory, ever-evolving labor of love that will never demand a surprise alteration.