As the alarm clock rang, she briefly saw the contours of a gushing hole through the window, which was staring back at her. She turned her face back into the nook of her arm, inhaling the faintest amount of air, hoping that this lack of oxygen would make her, if not numb, at least sleepy again. But someone—perhaps her mother—flushed the toilet, waking her completely and providing an explanation for the previous image in the window, which appeared before her anew. For days it had seemed as if the rain would never come to an end, but in the enclosed bedroom, the rain was inaudible.

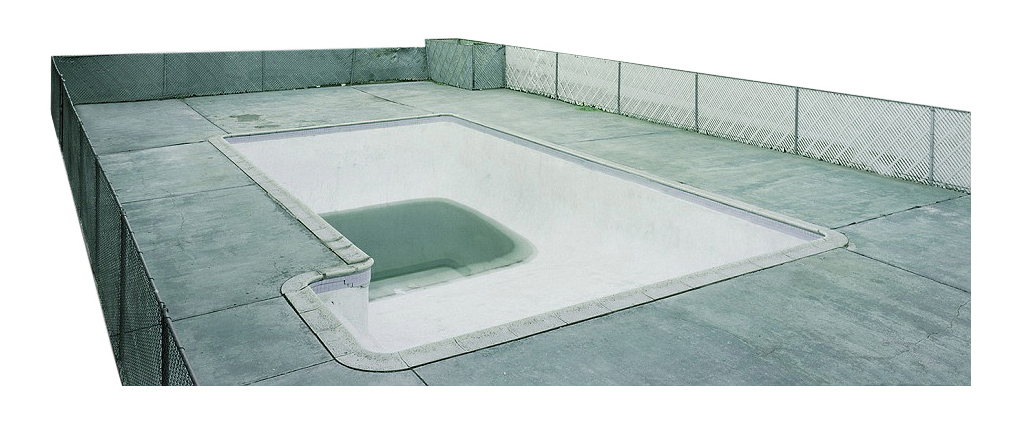

Over the past few months, an area meant for a medium-size swimming pool had been excavated in the backyard. After a leveling machine was brought in, the diameter of the area expanded continuously and then, for security reasons, was enclosed by a metal fence. It seemed the property management had run out of money since the construction workers had ceased work indefinitely a few weeks ago. Because of the recurring cascades, the inner walls of the basin started to show wear. She had noticed for the first time this morning a growing hole, proportionate to that of a human head, which gargled like a clogged drain. There was no notification for the tenants at the house’s entrance, but sometimes she considered writing one herself.

It was 2003, but also 20 years later. In the meantime, some circumstances had not changed. Her parents had moved out of the apartment above her, and were replaced by someone or rather a “group of someones” who made the same reassuring sounds in the mornings, with the exact same predictable uniformity, sounds that she could still remember from childhood.

“Where is the table tennis table from the backyard?” She could never think of anything better than that and the question was seriously getting old by now. The desire to write a note for her neighbors had become somewhat automated, like how she looked at the clock without really taking note of the time. The further she slipped into a waking state, the more she was plagued by a recurring if not compulsive thought that emerged for the first time when she spotted the April ’99 issue of the American Rolling Stone in the Berlin department store KaDeWe. At that point she was 11 years old and emotionally blackmailing her mother into buying the magazine with the proviso that it would improve her English comprehension. The cover girl was Britney Spears, then only 6 years older than herself, lying across pink satin sheets, dressed in pajama shorts and an unbuttoned top exposing her black bra. Britney held a telephone receiver in one hand and a purple Teletubby in the other. Only two out of the five headlines encircling her overlapped her figure: “Britney Spears—Inside the Heart, Mind & Bedroom Of a Teen Dream” and the seemingly ill-considered “Lost Tribes Of the Amazon.” Instead of wondering about her daughter’s choice and tastes, her mother burst out laughing: “If he would have liked that better?” She was still at an age where questioning one’s parents came from a place of genuine curiosity. From that moment on, the story of he and her mother’s guilt started to unfold. During the same car ride in spring ’99 with the magazine open across her knees, she was confronted with her own entanglement with the myth for the very first time.

After German philosopher Theodor W. Adorno refused to write a favorable assessment for the leaflets of the political commune, Kommune 1, that was wrongly accused of having been encouraging students to commit arson, he accepted an invitation by the German department of the Freie Universität to hold a previously scheduled lecture. Instead of giving in to the demands of the SDS (the Socialist German Student Union) and engaging the students in a serious political debate, possibly explaining his refusal to comment on the pamphlets, he presented them “On the Classicism of Goethe's Iphigenia” on July 7, 1967. At that point Fritz Teufel, a founder of Kommune 1, was still in preventive detention. Outraged students camped in the foyer of the auditorium distributing flyers, which took offense at the professor’s inconsistency. The murder of university student Benno Ohnesorg hadn't been that long ago. Among other things, the flyers read, “Adorno does not take place in the revolution. May his words rot in his mouth.” Her mother still kept those flyers in a cardboard box at the bottom of the laundry cabinet at home. She could still recite some paragraphs by heart, and often in the most unsuitable situations. Nothing in her voice gave away her former impatience toward Adorno's theories; there was no trace left of any despair or urgency. She didn’t let any of that Actionism out, not even by throwing pudding powder at parents' evening at her daughter’s school. Retelling that story now, she sounded more like someone who would have loved to be Adorno’s muse, Arlette Pielmann, in secret.

The protesting students not only attempted to undermine Adorno's speech in the days before but also disturbed the lecture while it was taking place. Although some of the disruptors left the auditorium in protest after an appeasing introduction at the beginning of the event, others decided to unfurl banners as soon as Adorno opened his mouth. Her mother, too, was among those involved, possibly holding a sign that read,“Berlin’s left-wing fascists greet Teddy the classicist!” or something to that effect. She imagined this headline on the cover of Rolling Stone. But to be entirely accurate, she only knew the slogan from one of the footnotes of a rather thin blue book by literary scholar Péter Szondi dealing with the students at the Freie Universität, who were protesting its technocratic university reform back in the 1970s. The explanation that “Teddy” was Adorno's nickname used by his good friends was only found in the small print. None of the banners described in the book were in her mother's cardboard box, nor were any excerpts or cutouts from newspaper articles stashed away. In fact, there was nothing that dealt with this one particular incident, just the slim book and the original flyers. The reason may not be that they were shameful but maybe that the memories simply did not exist at all.

One day, however, her mother told her the story of her own mother’s hidden memorabilia, which she found accidentally as a young adult. At that naive age, she burned them and tried to get rid of the few remains by washing them down the toilet—those ashes and metal pieces that were unwilling to melt. Unfortunately, the pipe clogged and caused a small flood, for which she was slapped in the face. Not much later she moved out and began her studies, sneaking around and following Adorno, but deep down just mistaking him for Herbert Marcuse. After that, the incident was not talked about anymore. The smart blue book did not reveal any of this. The only valuable plot point worth printing outlined the minor discrepancies between the students in the auditorium, during which some of the banners were destroyed. Her mother made her grand appearance shortly after the lecture. Back in 1999 she told her for the first time how she tried to give an inflated red rubber teddy to Adorno as a gift. During the act a fellow student hit it out of her hand, before Adorno could even react to that carefully rehearsed provocation. In About the Freie [viz. free] Universität, this part of the story was worth a font size 6 or even less; her mother was nameless and her role was summarized in two sentences. “This is an act of barbarism!”—or something very close to that—was how Adorno commented on the scene. Of course, this comment fit perfectly into his previous interpretation of Goethe's Iphigenia in Tauris, emphasizing less the heroine as an embodiment of a humanistic ideal of its time, nor placing the fantasy of the thoroughly pure and transformative soul in the center of his reasoning, but shedding a light on the barbarian King Thoas.

“The song that put Spears on top is a strutting statement of intent called ‘...Baby One More Time’—and that ellipsis tells a tale. The three dots mask a chorus hook line—‘Hit me, baby’—that some have taken as a masochistic come-on. ‘It doesn't mean physically hit me,’ says Spears. ‘It means just give me a sign, basically. I think it's kind of funny that people would actually think that's what it meant.’”

She could only understand about half of what that English article was going on about, but she was too impatient to wait for a calmer setting to dive into it. Not caring about the slight car sickness she started to feel building up in her stomach, bits and pieces of her mom's continuously flowing monologue oozed into her subconscious.

When she decided to call her mother as the newly released music video for “Oops!... I Did It Again” played on television in 2000, she quickly became disillusioned. While her mom's identification with the Rolling Stone cover photo surfaced very quickly, the correlation between the red teddy made of rubber and the strange latex outfit of the pop icon was not immediately obvious. Returning to her work desk, after only shaking her head, the mother deemed every attempted explanation from her daughter impossible. Still fixated on the screen and canceling out her mother’s exit, an important reality slowly dawned on her: Only she would be able to piece the smallest parts of the myth back together.

Just recently she had finished her assignment to read Goethe's Iphigenia in Tauris during her summer holidays for her literature class. According to the curriculum the students would learn how to contrast one of the many adaptations of the tragedy with the original written by Euripides. Sensitized by her mother's fate, she began digging around the footnotes and epilogues of various editions. It was here that she discovered the kernel that Goethe had used for creating his ideal female image of self-determined humanity. Even the diary entry of the German poet was cut and compressed into merely two sentences, doomed to be found in the small-printed lettering of the footnotes.

On his famous journey to Italy, Goethe discovered an image of St. Agatha in the Palace of Ranuzzi that struck him as a steadfast virginal portrayal. He was impressed by his observation of the religious painting insofar as it managed to appear without any coldness or brutality. Goethe had wrongly attributed the painting to Raphael. To this day, she was still unsure of the exact slogan her mother was waving around during Adorno's lecture, so she was willing to forgive Goethe’s s misjudgment. But when she went to the biggest public library in the city to browse around for pictures of the saint, she ended up being startled by Goethe's choice of words to describe the saint. They seemed misleading since Agatha did not really look conservative or demure. Either she smiled slightly and glanced over a bowl filled with two breasts, which she balanced casually—or she was clutching and wrapping sheets stained with blood around her upper body. Agatha expressed a state of agony that didn't fail to estrange her.

She had just turned 13 and was filling her own shoebox already. Layering third-rate music magazines, school notes, and ripped-out pages on top of one another, information on Britney, Iphigenia, and now Agatha of Catania was piling up fast.

According to the legend, Agatha, like Iphigenia, also rejected a courtship. In the saint's case, the romantic persuader was the pagan Roman prefect Quintianus, who, upon dismissal, threatened and persecuted her for practicing Christian faith. Soon after, he had her hung up by her hands from a wooden beam, ripping her breasts with pincers before burning and cutting them off. After various tortures she was saved by an earthquake interpreted as a sign by the enraged citizens of Catania, before Quintianus had the chance to burn her at the stake. She was sent to prison, where she died her fictitious death around 250 AD. One year later those citizens stopped the lava flow of the erupting Mount Etna using the veil of the martyr. In remembrance of her, the citizens of Catania bake little buns in the shape of breasts. The so-called “Saint Agatha's bread” is said to have a soothing effect on different variations of burning chest pains, which Iphigenia experienced plenty across the dramatic texts.

At the age of 14, the daughter began to read hagiographic literature in her free time, simultaneously trying to pick up some Italian. Soon discouraged, she stopped not long after starting, still being 14 years of age, as Agatha was when she refused Quintianus. When she consequently decided to recruit friends from school to train, instead, in archery, her parents felt they had to put their foot down to stop their daughter from delving into the abysses of Amazonian cults and customs. In her mother’s opinion, those interests went too far.

“Those who only let dear Adorno decide will uphold capitalism all their life.”

Strangely enough, she found many newspaper articles dealing with convenient explanations for Adorno's sudden death. The snippets involved a lot of finger-pointing that surfaced when she was rummaging through her mother's drawers. She knew that this was at the core of everything she had carefully reassembled by then. About two years after the incident at the Freie Universität on the April 22, 1968, three women wearing leather jackets stormed into Adorno's lecture called “Introduction to Dialectical Thinking.” They encircled him and attempted to kiss him while exposing their breasts and sprinkling blossoms of roses and tulips about. He tried to shield himself and ward them off with a briefcase, but eventually he broke down and fled the auditorium crying. Because of the continuous student riots, which were becoming increasingly violent, he was forced to put his lectures and seminars on hold. “Introduction to Dialectical Thinking” was the last one he gave in front of his students before his death in 1969.

It is again 20 years after 2003. She was breathing a bit heavier now and leaned half her body out of bed to reach the handle of her balcony door, tilting it open to let some fresh air in. If her mother would have been one of the three participants involved in the “breast incident,” her own hagiography would maybe match up.

For days now, the rain had pressed down on her, refusing to stop. The drain hole in the wall of the pool was no longer frothing up, but appeared veiled and obscured. Just one hour had passed; it was seven o'clock. However, she was twisting and turning, thinking back and forth, recounting and recalling anew the relationship between her and her mother. There was indeed an ellipsis that told that tale.