Jean-Michel Basquiat had a professional career that lasted just nine years, but in that time he managed to make himself one of the most significant painters of the 20th century and an enduring cultural icon. Basquiat was a bundle of contradictions; he made art from the streets, yet his work appeared in galleries throughout the U.S. and Europe. He was among the first black artists to be internationally acclaimed, but was completely unschooled and nontraditional in his methods.

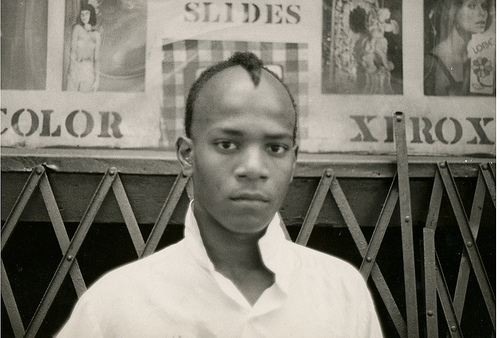

The painter epitomized cool with his confident and nonchalant aura, his eccentric wardrobe, and of course, his hair. Basquiat’s hair went through many different stages throughout his professional career, but aside from the time he spent as SAMO (immediately upon moving to New York, see above), all his hairstyles follow more or less the same silhouette: the faux dreadlock that somehow suspends itself straight up in the air.

Twenty-three years after his death, Basquiat remains culturally salient, not only for his art but for his persona and visual aesthetic. After all, he is the guy who painted in Armani suits. These days, his visual legacy may be as important as his contributions to fine art. So much of Basquiat’s involvement with the art world is framed within the context of his public reception. He was their “noble savage” — the untrained, uncouth native artist, an urban black male who approached art intuitively, going against the Western canons and traditions. This relation appears in his rough-and-ready approach to painting, his juxtaposition of African bushmen art with text from Gray’s Anatomy, and his graffiti-centric themes and painting style. But the image most readily available for dissection by the mainstream was his own aesthetic. To the world his art was prefaced by his style, a black man with the hair and wardrobe of a savage, engaging in the world of the artistic elite.

With this in mind, it makes sense that Basquiat’s aesthetic seems to be shaping the grooming choices of the U.S.’s artsy, urban black males. Peer at the domes of some of the most recognizable young men in today’s street style scene: Joshua Kissi of Street Etiquette. Jean Lebrun and Eaddy from the Jersey Street Klan. Kadeem Johnson of KJohnlaSoul. That steezy model from Très Bien. And those are just the guys I know about. The cutting edge of contemporary black male style still plays with variations on what Basquiat sported for so many years.

[r]Jean Lebrun and Kadeem Johnson (from The Aveder Outfit)[/r]

All the aforementioned “new school” models, bloggers, and photographers occupy the ironic context of the refined black man, a careful juxtaposition of intellect with traditional “savage” themes of Africanism and urbanism. As both the first black artist welcomed into the fine-art world and the one who famously never had to sell out in order to do so, Basquiat’s style appeals to a new generation looking to be acknowledged without having to be palatable. The fashion of the aughts has been very 1980s-reference heavy, and for black men there’s one figure from the ’80s art world who stands apart as worthy of aspiration and emulation.

[l]Joshua Kissi of Street Etiquette[/l]

With his influence on urban style, Afrocentric thought (black pride, racial consciousness, social awareness, etc), hip hop, and grafitti, Basquiat set the culture that the Native Tongues would inherit. He died in 1988, right as the Tongues’ most prominent group, A Tribe Called Quest, debuted. They were the next in line of the same cultural lineage that Basquiat’s work was born of, helping spread the appeal of Afrocentric imagery in both the mainstream and within the circles of the artists that would inherit their place in black culture. Black artists and intellectuals in contemporary high art and fashion are continuing the same conversation. But as Q-Tip says in his post-Tribe solo work: “Don’t you ever forget who put the pep in your step / We made it cool to wear medallions and say hotep.”

[r]Très Bien’s proprietor of steeze[/r]

By now, the trope of the intelligent and cultured black man has recurred enough that today’s black creatives can avoid a lot of the obstacles Baquiat faced. Creatively and intellectually driven in part by the African-American experience, today’s black artists focus on forging a culture that won’t allow their heritage to be burned off by the heat of growing mainstream acceptance. The result is dreadlocks and similar hair, coupled with symbols of intellectualism and cultural refinement. It’s a spectacle the industry is embracing too. There’s still an art-world awe surrounding anyone who is able to break the stereotypes concerning black intelligence and the merit of black art without losing too much of the stereotypical blackness that traditionally symbolized wildness and a lack of refinement. Dreadlocks, tribal prints, and tribal beads coupled with tailored chinos and loafers are the contemporary equivalent of African graffiti art lining the walls of an European art gallery. They’re both the brash play of traditionally irreconcilable worlds, increasingly common in modern culture, thanks to those who pushed barriers in the past.

Perhaps it’s the continued tension and awe surrounding this unapologetic Afrocentrism that sustains its commercial viability. Some of the most avant-garde cultural conversations in fashion and art can only exist within the context of this juxtaposition. Maybe the moment all of this stops being so paradoxical or novel, much of the commercial and mainstream appeal will go with it. Basquiat’s demise was due in part to the loss of his novelty within the high-art elite. It stands to reason that as cultural tones and societal values evolve over time, the manner in which blatant Afrocentric art and fashion is perceived will have to adapt with it. This productive tension will continue giving birth to new styles, new movements, and new cultural conversations.

[r]Michael dos Santos of An Educated Guess[/r]