The famous photograph by Étienne Carjat, taken in December 1871. A grainy image, the contrast between the black and white simplifies the face, posterizes it, popifies it. It is a portrait that almost begs for the Andy Warhol or the Roy Lichtenstein treatment.

The poet is 17 years old. He wears a dandy’s cravat and a shabby suit. His expression—with its insolent pout and vacant, sociopathic stare—cannot obscure the feminine delicacy of his nose and the soft curve of his boyish cheeks.

No one who meets Rimbaud during this period fails to mention his cherubic face, which enters posterity through this image. This is the face of the original enfant terrible, the face that will hypnotize Jim Morrison and Patti Smith into poetry, the face heartthrobs Leonardo DiCaprio and Ben Whitshaw will be hired to resemble in Total Eclipse and I’m Not There. But by framing the shot around the head and shoulders, Carjat hides from the viewer the freakishly adult body beneath: all six feet of it, lanky, with ruddy skin, terminating in a pair of monstrous hands. The choice is deliberate. Carjat’s photographs are every bit as caricatured as his satirical drawings for the feuilletons; he is not so much interested in capturing the poet’s likeness as creating his myth, and to create a myth requires excision just surely as it does embellishment.

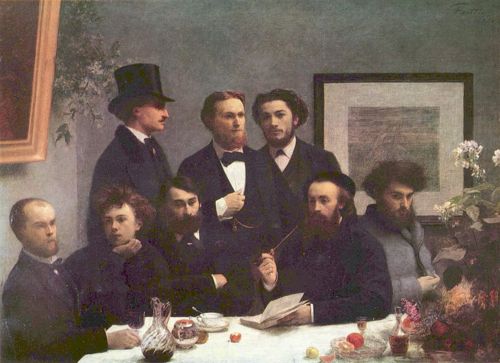

To the same end, Henri Fantin-Latour’s 1872 group portrait Un Coin de Table only gives us a half-length Rimbaud. Second from the left in the portrait, Rimbaud is sitting down. Once again he stares off into the distance; his cheek rests dreamily on the heel of his palm, in an obvious reference to the cherub in Raphael’s Sistine Madonna. Angelic as it was, the face of the real Rimbaud was just up the neck from the body of a farmer; though boyish, it was attached to the body of a man. At 17, less than a year before he writes the first of the Illuminations, a collection of 40 poems in prose and two in free verse that will change world literature forever, he is already a walking contradiction, a centaur.

***

Carjat’s photo is the one that adorns my copy of Illuminations, a New Directions paperback translated by Louise Varèse, which I discovered as a 14-year-old boy, browsing the shelves of the Bodhi Tree Bookstore in Los Angeles. A detail from the same image also appears in triplicate on the cover of John Ashbery’s new translation. Framed tightly around the poet’s eyes, the cropping is even more in thrall than the original to Rimbaud’s legend, which has only multiplied in the 120 years since his death.

My adolescent reading of Rimbaud was typically romantic and, though I’m not proud to admit it, aspirational. Well did I remember my school librarian’s pointed observation that, unlike in mathematics, music, and chess, there were no prodigies in literature. Here, I thought, hiding a petulant sneer with my copy of Illuminations, were two exceptions! How could I have known that the same scene was repeating itself in study halls across the world?

As a result, I missed the poems for the poet. Opening to the text of “Cities (I)” or “Anguish” or “Genie” I saw only the boy genius, the tragic lover of the poet Paul Verlaine, the scourge of bourgeois morality, the alchemical experimenter with art and life, the synthesis of dirty angel and devil immaculate.

What impressed me most, though, was not what Rimbaud had written but his decision, at the age of 20 and at the height of his poetic powers, to renounce Paris and poetry for an obscure life as a coffee merchant, gunrunner and adventurer in the Orient: in the Dutch East Indies, in Yemen, in Abyssinia, returning to France only to die, at the age of 37. Why did he do it? The question kept me up at night, as it did, I would later discover, legions of biographers, critics, academics, and poets.

Naturally, the answer I preferred was the one that put the most heroic spin on Rimbaud’s behavior. Like Wittgenstein and Beckett, whose writings I was also discovering at the time, Rimbaud practiced what Susan Sontag called “the aesthetics of silence.” On this interpretation, his poetic experiments led him beyond the limits of language, where he came to see the vanity of writing itself -- how, as Auden would remark 70 years later, “poetry makes nothing happen.” And so he hung the mask of the man of letters back in the gallery of history where he had found it and took in its place the mask of the man of action. “Enough seen…Enough had…Enough known,” he writes with sublime world-weariness in a poem fittingly titled “Departure.” Far from marking the end of his career as a poet, I considered Rimbaud’s escape from Europe his greatest masterpiece. To me, his life in the Orient was nothing less than an “immense opus” in which his mind spent its “illustrious retirement” (“Lives”).

Only now do I see that this interpretation was one that befitted the aura that emanates from a famous photograph rather than one gleaned from an understanding of a flesh-and-blood human being. Adolescence may have been Rimbaud’s great theme, but when I first encountered his poetry, I was too young to realize that he was already writing from the other side, as one who had crossed over into adulthood, a strange land whose geography I could not yet envision. I did not notice that Rimbaud surreptitiously dedicated Illuminations to “the adolescent I was” (“Devotions”). Rereading the poems a lifetime later, I am struck not so much by Rimbaud’s devil-may-care swagger or even his precocious genius, but by the bitter pathos with which he mourns childhood’s end.

***

The poems of Illuminations are like a surreal metropolis that has descended into anarchy after all the adults have fled or been murdered; it is a city populated by beggar children, fairies, barbarians, genies, utopian dreamers, and “princesses of tyrannical gate and costume.” Surrounding the city is nothing but hostile terrain, asphalt deserts, ice floes, and polar rubble. The sense of doom is pervasive. The poet promises to “massacre logical rebellions!” (“Democracy”). He prays to “Waters and sorrows” that they may “rise and revive the Floods” (“After the Deluge”) and wonders whether it is possible to “become ecstatic amidst destruction, rejuvenate oneself through cruelty” (“Tale”).

Apocalyptic thinking combines fear and desire in equal measure. From the time of John of Patmos to the present day, it represents the inability to imagine what the future will look like and a last-ditch effort to universalize one’s own mortality. Like Saint John, Rimbaud was an apocalypticist in all senses of the word—a seer or visionary, a receiver of revelation, one who prophesizes the end of the world. But for Rimbaud, the apocalyptic moment is not his death or the decline of his nation or culture but the passing of his youth. “It can only be the end of the world as you move forward,” he wistfully writes in “Childhood.”

Few people experience the rupture of growing up as profoundly as Rimbaud did; the normally porous transition between childhood and adulthood was for him a radical dislocation. Poetry and adolescence were synonymous in his mind; when the latter came to an end, so too did the former.

Poetry did indeed fail Rimbaud, but in a more mundane manner than I previously thought. In his essay on the uncanny, Freud observes that writers, like children and primitive peoples, engage in magical thinking; they sustain much longer than their peers the illusion that their words have the capacity to bend reality to their will. Magical thinking was at the heart of Rimbaud’s theory of the visionary, whereby through an “alchemy of the word,” one could hallucinate factories into mosques, drummers into angels, and whole salons at the bottoms of lakes (A Season in Hell).

Reality, however, proved “too prickly for [his] lavish personality” (“Bottom”). It appeared in the form of a bullet, fired at him by Verlaine, in a dingy hotel room in Brussels. Verlaine, who would compile Illuminations into their present form long after Rimbaud had already fled Europe, is the unnamed center of the book. He is the genie whose face makes promises “of a multiple and complex love! Of an unspeakable, even unbearable love!” (“Tale”); his is the heart that “beats in the belly where the double sex sleeps” (“Antique”); he is “the enchanted rack on which [Rimbaud was] stretched” (“Morning of Drunkenness”).

But neither Rimbaud’s poetry nor his body, which had held Verlaine captive for four years, was ultimately capable of persuading Verlaine to leave his wife, let alone of making the Bacchic projectile fly from its course, as it had for Orpheus. The shot only slightly wounded Rimbaud, but the incident inaugurated what he called “the time of the assassins” (“Morning of Drunkenness”). Verlaine, now known to be an alcoholic and sodomite, underwent involuntary psychiatric examination and spent two years in jail, where he, to the younger poet’s great disappointment, converted to Roman Catholicism, though not to sobriety. The failure of their “pure love,” a common enough experience for adolescents everywhere, prompted Rimbaud’s own conversion: from the most gifted poet of his age to a “lord of silence” (“Childhood”).

***

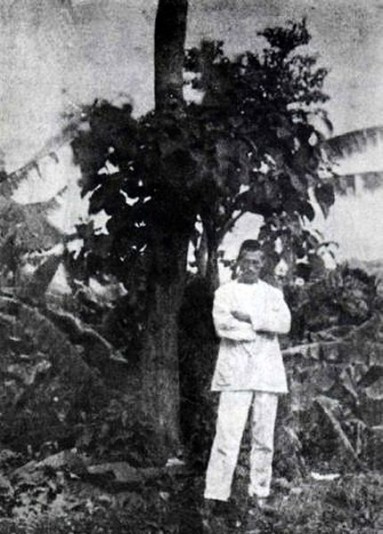

Harar, 1883. The coffee merchant sets up a camera and takes a self-portrait. He stands in front of a tree, wearing a simple white tunic and white trousers. He wears his hair short, in a military style. His arms are folded across his broad chest. The full-length portrait gives us a good indication of his height, but it obscures the one thing that all the previous photos of him take special pains to emphasize: his face, which here is nothing more than an ill-defined smudge.

The personality of the adult Rimbaud, who writes letters home to his mother detailing and bewailing the state of his finances, is so different from that of the adolescent poète maudit that it seems improbable that the two belonged to the same person. Then again, Rimbaud, like us all, was always full of contradictions. No one has so perfectly captured the alienating feeling of being on the threshold between childhood and adulthood than the 16-year-old Rimbaud who wrote, “I is someone else.” That quite natural sentiment was no doubt exacerbated by his arrival in the literary world of Paris, which would insist on treating him as a myth rather than as a man.

The dissolution of self and personality that characterizes his last poems and the Harar self-portrait are not so much a prefiguration of the “death of the author” thesis—as many, including Ashbery in the introduction to his translation of the Illuminations, have claimed. Rather, the poems tell a more mundane story: Rimbaud realized that adulthood would not accommodate the persistence of his art. In his case, the death of the author was nothing more than the birth of the man. If we have difficulty seeing that, it’s because whenever we’ve looked at Rimbaud, we’ve never gotten the full picture.