China’s command-like economy may be better suited to cope with technologically driven abundance

For years, China’s country’s growing spare capacity and rising investment have worried outsiders like me about the sustainability of its growth model. The idea that Chinese demand for resources—which were ultimately being used as much for manufacturing for the export market as domestic-based consumption—was indicative of a competitive and sustainable global bid for goods and output seemed to me unconvincing. Especially without evidence that any rebalancing from investment and export-driven growth to consumption-based growth was really happening.

Two things have since led me to adjust my opinion.

The first was an encounter with a Chinese fund manager in Geneva about two years ago. Ever mindful of not being brainwashed, I came prepared with what I considered an extremely convincing argument for the case against the Chinese investment case. But rather than have my case knocked down, the fund manager never hesitated to agree with every point. It was confusing.

“How can you justify the case for Chinese investment when excess capacity in the building sector is running at the rates it is?” I would ask. Analysts have anecdotally reported overcapacity in China’s industrial, building and manufacturing areas since the crisis began.

“You can’t,” he would answer.

“And what about the untold volumes of encumbered commodities masquerading as demand?” Official data is hard to come by, but Chinese financialized commodity stockpiles, mostly used to raise cheap collateralized funding that is then reinvested in higher yielding Chinese wealth-management products, have been reported in everything from copper and aluminum to cotton and consumer goods.

“Yes, this is definitely happening,” he would agree.

“And investments in risky Chinese wealth-management products and overall credit intensity in the economy?”

“Yes, all of this is true,” he’d happily agree.

“So how do you justify the case for China? Why don’t you think it will overheat or suffer a dangerous credit implosion?” I volleyed back.

The answer, which at the time seemed to me unconvincing, was simply, “Because China is different, and foreigners don’t really understand how. It is a different mentality you are dealing with.”

This corresponds with the second incident that led me to adjust my opinion: a research note by James White, a little known Australian analyst at Colonial Asset Management.

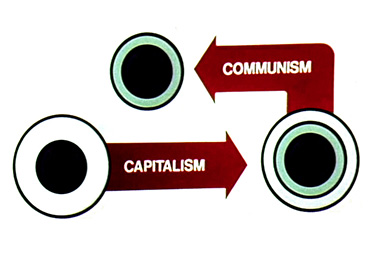

His argument was simple: What western investors forget about China is that it doesn’t operate according to the standard rules of capitalism. It is to some degree a postcapital or “proto-post-capital” economy. This one fact helps China defy doomsayers’ predictions time and time again.

His research arrived as I was re-evaluating my understanding of my causation of the 2008 global financial crisis—distancing myself from the idea that subprime loans were to blame and moving toward a more general thesis that the roots of the crisis lay in the dotcom bust of 2001, a surplus of investible capital, and the Western capital system’s general struggle with technological abundance.

One need only to think about how you put a value on abundant air to understand the problem. Values in the capitalist system are set by marginal availability, not utility. As technology leads to greater abundance of goods and resources and displaces the need for conventional labor with it, this has the habit of devaluing capital. At this point, the more capital is invested in capacity, the more the system is flooded with goods and output that can’t be fought over in the traditional competitive manner that drives prices. It is consequently only by spreading wealth around without any return conditionality attached to it at all, or investing without a fear of loss or even break-even return as can be done in China, that you can stimulate the sort of consumption that can keep prices supported.

What White was saying fit that picture perfectly. China was able to succeed where Western economies couldn’t precisely because it valued and understood capital differently. For China, capital was just one component of a much bigger economic game that was ultimately focused on raising living standards of all households irrespective of capital returns.

Overinvestment and default risk were for China by and large irrelevant. Indeed, China could tap spare capital by the 1990s, because conventional return to capital in the West was already lacking and the People’s Republic, unlike Western economies, was prepared to deploy and underwrite investment without fear of any risks of unprofitability. China’s epic stimulus programs after the 2008 crisis, enacted without hesitation, show the nation’s readiness to socialize losses when it matters for the economy.

Some judged what followed as China being able to look beyond the needs of today to the very long term. As long as China was patient, the investment-led growth would be justified on account of the sheer number of people that could stand to benefit from the urbanization. Yes, there are stacks of empty houses, buildings and ghost towns in China. But the rationale is that unused capacity will eventually be demanded by China’s inland populations once they begin to benefit from urbanization and development.

But there is possibly more to it than just very long-term thinking.

Consider John Maynard Keynes’s coalmine experiment. On the theory that having people employed for no purpose at all can help to stimulate economic activity during times of demand collapse or output shock, he proposed having a government fill old bottles with banknotes, bury them in coal mines, and encouraging private enterprise to compete to dig them back up again. The process would employ many more people in jobs, albeit pointless ones, and thereby spread wealth around. Keynes argued it would naturally be more sensible to have these people employed in building houses or something else more useful. But the economic effect would be the same.

In many ways, what White is arguing is that China is actually running the greatest Keynesian coal-mine thought experiment of all time, building and producing not for the sake of what was produced but rather to take advantage of a global capital surplus. This gave China the opportunity to empower its citizens on the condition that underwriting the capital could woo it in the first place through this massive social experiment. It did so, of course, by means of foreign-exchange manipulation—an important precursor to the quantitative easing (QE) used by the U.S. Federal Reserve postcrisis—that ensured that every dollar invested in China would offer a better payoff than a dollar invested at home. It could guarantee this because not only would there always be a superior Chinese bid for the capital in question but it would be coming from the government directly.

It is only because the government is putting up the bid rather than private enterprise—which in emerging markets is thought of as risky and suffering from corruption and other principal-agent problems—that the capital suddenly becomes free-flowing to the country in question. If it wasn’t the government providing the bid, it would be seen as too risky to invest. But since the government can print money ad infinitum, and this is what Chinese currency manipulation really consists of (buying dollars with newly printed yuan), that bid remains competitive for as long as the Chinese government wants it to be.

The Western version of QE sees the Federal Reserve printing money in order to absorb underperforming assets and U.S. Treasury bonds into its coffers in a way that effectively underwrites their performance no matter what and squeezes the market at the same time. The Chinese FX manipulation version of QE saw the government printing money in order to absorb abundant dollars out of the global system, in a way that effectively kept the dollar overvalued no matter what. This meant investors could be sure that their dollar denominated investments in China would always result in real returns.

The reason the Chinese government felt comfortable underwriting bids for foreign investment, meanwhile, is probably because its socialistic disposition allowed it to see what the West couldn’t: namely, that in the West, capital was no longer scarce enough to justify a truly competitive bid for it and all China had to do was provide some sort of guarantee in order to benefit from it.

At the end of the day, the much discussed “savings glut” is just another way of saying capital surplus. For years nobody really understood what was fueling it, but more recently Larry Summers speculated that it was the first clear symptom of “secular stagnation,” a trend that arguably started in the early 1980s. In a secular-stagnated economy, we end up with a capital rather than labor bias, which sees rents and returns flow to owners of capital in favor of labor, to the detriment of the wider economy.

Unless that surplus could be redistributed to new pockets of demand, all roads consequently lead to a demand collapse, because eventually all wealth becomes concentrated in the hands of technology and capital owners rather than in labor’s hands. This creates a vicious demand circle that impoverishes the economy overall.

For China to benefit from that capital surplus, all it needed to do was draw the capital over and keep it there, creating a self-enforcing capital scarcity—or savings glut—for the world. With its socialistically minded economy that didn’t mind investing capital for public purposes regardless of return, China prevented that capital from returning to the West. This is important, because if the capital was allowed to flow back to the West, it would have less of a distributive wealth effect than it would in China, where it would make more people feel more rich. In the West, it would more than likely end up concentrating in the hands of capital owners, who would be ever keener to employ robots than human beings.

In that sense, China became to the world what the Doozers are to the Fraggles in Jim Henson’s Fraggle Rock: building and producing raddish-based constructions not out of personal or even global need but rather because it gives them purpose. Hence when the Fraggles come and consume that production, the Doozers don’t mind at all. The destruction provides them with an excuse to build some more. The more the Fraggles consume, the happier the Doozers get. The less the Fraggles consume, the more the redundant constructions the Doozers build and the more likely they are to question the point of their existence.

This is something the West, and its scarcity-focused value system, has failed to understand. Capital abundance created an investment paradox, which dictated that an economy could benefit just as much from giving capital away to anyone, be it through public investment, government spending, credit expansion through overinvestment, or even squandering capital completely—as it could do from allocating it wisely and proportionally. Those who were prepared, like China, to deploy capital for public purposes rather than have it serve the competitive bid exclusively were much more likely to stimulate their economies than those that don’t.

As White argues, this is why it’s wrong to assume that China is pursuing capitalism as we know it. Its real aim is to create a hybrid model of public investment and very aggressive market-based competition with the hope of creating consumer surpluses rather than economic rents. This would distribute wealth more widely than if it was passed exclusively to rent seekers alone.

Capital is allocated consequently not on the basis of whether the asset created can provide a return but whether it serves a greater social purpose. The Chinese government will consequently fund contractors to develop public infrastructure and other massive social projects, as well as backstop private enterprise that has potentially overinvested in private developments. Even if the projects don’t yield a monetary return, they improve the social infrastructure, Chinese mobility, and the general standard of life. By contrast, in the United States, the lack of guaranteed returns has created a major underinvestment problem in public infrastructure, which is now falling apart or becoming ever more dangerous as a result.

As White notes in a more recent report:

Success at the national level will generally come with failure at the micro level. The lack of a return in certain assets is offset by faster productivity growth which encourages activity growth. As such the returns on investment flow away from the individual capital allocators towards more productive labor enjoying faster wage growth and the government capturing the benefits of higher levels of economic activity through taxation.

Though there are a few factors to bear in mind.

First, the strategy depends on there being concentrated pools of surplus capital in the first place. Second, the strategy only works for as long as the West doesn’t figure out it too can benefit from socializing capital losses and thereby beat China at its own game. Third, capital controls and a fixed currency—which block direct investment into China, and Chinese investment outside of China—are necessary to prevent the misallocated capital being (de-)valued according to Western standards. The appointment of Janet Yellen as U.S. Federal Reserve chairman and recent policy action to widen the currency band by the People’s Bank of China suggest some of these factors are potentially being disrupted already. If that is the case, it stands to reason the benefits of unconditional capital distribution could soon start flowing to the West in lieu of China.

The consequences of such a transition would likely be stimulative and thus inflationary for Western economies. They might also end up having a profound and counterintuitive effect on commodity prices. Inflation, after all, is generally a symptom of an output shortage and thus something which makes investing in new capacity—not commodities—extremely profitable and low risk. This raises the question: Why would a rational investor forgo such an opportunity to take an unhedged position in commodities in a genuine inflationary environment? Why would you invest in commodities that change in value and can lose you money when you can invest in a bond that guarantees you your money back plus some?

If that reluctance stems from the idea that Western capacity would end up competing with Chinese capacity for a finite amount of resources, it appears logical. But if you consider that new commodity-using ventures would signal their commodity needs to the market directly anyway, that could instead provide a compelling cash-out option for opaquely hoarded Chinese commodity inventory. Western resurgence might then, instead of bidding up commodities, tempt Chinese financialized players back into Western markets—where they become much more visible and price-impactful—knocking commodity prices and/or global commodity production significantly in the process.

Ironically, this would augment the argument for yet more unconditional investment in China. This new investment would continue to expand one of the biggest social experiments in economic systems in history.