Heavy footsteps from behind. Authority in each step, the march forward to the photograph on the wall making the gallery floorboards creak. Commanding feet break silence, thunderous steps claim space. The white, manicured index finger points to the photograph on the wall, aiming, directing, identifying. The sweet, exuberantly sweet, cooing and coddling voice saying to a child locked around arms, “Look, David, it’s a clock.” There in a sentence, the direct address, a mother, holding her toddler, points to the Wojnarowicz photograph on display, Untitled (Time and Money), reducing it to but an object in photographic stillness, the finger pointing to piece after piece in this retrospective at the Whitney Museum, David Wojnarowicz: History Keeps Me Awake at Night.

Yes, I see it too. A clock. Photographed simply, in black and white, mounted to the wall to be viewed by the paying customer. That is what it is, after all, a clock with its hands telling time; surely, that is what it is not, just a clock, a measure of time, a school-day lesson to be learned. Maybe the babysitter had the day off. Maybe daddy needed the day off. Maybe this mother thought a day out at the art museum pointing to the clocks and the flowers and the dinosaurs in the artworks of queer artist and AIDS activist David Wojnarowicz was a nice way to spend this Saturday. How does one respond to the art of AIDS? To the AIDS-informed art produced by Wojnarowicz? With seriousness, with mourning, with pleasure, with the pointing of a finger?

I share this morning here at the Whitney with this mother and child, keen to their presence. How could I not be? Her heavy steps, the squeaking of the stroller wheels, the child’s screaming. My mounting frustration over how easy she can point, how easy she can reduce a painting, how easy it is for her to move through this exhibition when I, at every turn, at every viewing, am upended, enraged, and destitute over my inability to imagine AIDS, its reaches, its depths, its power. The urgency of AIDS, as inscribed in the various pieces in the retrospective, is historically specific, and to account for that urgency, to remotely grasp or fathom it in our current context is something a lot harder to do. ACT UP New York staged protests here at the Whitney to curb such cultural amnesia about AIDS, which the Whitney’s curatorial schema was reproducing. AIDS as something of the past, ACT UP was contesting, AIDS as something that is over and done with. In response the Whitney updated the placards to highlight ongoing HIV/AIDS activism and how the disease still matters today. Is this amnesia, this ignorance of AIDS’s relevance, what explains the movement of the mother across the space? Is that what accounts for my immobilization at almost each and every piece? The unimaginability that is AIDS?

I watch as she strides past the section of the gallery where photographs have superimposed text, textual excerpts from the many essays Wojnarowicz writes. Untitled (When I Put My Hands on Your Body), 1990, is a photograph of the bones of indigenous people that were once on display in the Dickson Mounds Museum in Illinois, which Wojnarowicz visited. “When I put my hands on your body on your flesh I feel the history of that body,” begins the first line of the superimposed text, a paragraph or so of Wojnarowicz’s sensuous writing, explicit in its queerness, explicit in its erotics. In one of his better-known pieces, Untitled (One Day This Kid…), is an image of Wojnarowicz as a child with text bisecting around him. Each sentence begins with, “One day this kid will…” and concludes with the queerness that the young boy will grow into, the queerness that will be political, the queerness that will be met with violence.

“Look, David, it’s a flower,” so she says, pointing, as she does, as she wills, at the painting Americans Can’t Deal with Death. This part of the gallery features several of Wojnarowicz’s flower paintings, paintings that also incorporate text with and as image. The canvas she points to is painted with a pinkish-white flower against a backdrop of green leaves. Two smaller, square images, depicting someone wearing a hazmat suit and the indigenous bones from the earlier photograph, are sewn into the bottom-right corner of the canvas with the signature red yarn featured in much of Wojnarowicz’s work. Two textual blocks taken from his essays are on the upper-left and upper-right side of the canvas. In I Feel A Vague Nausea, another flower painting, the concluding sentence of one of the textual blocks goes as follows: “I’m the robotic kid, the human motor-works, and surveying the scene before me I wonder: What can these feet level? What can these feet pound and flatten? What can these hands raise?” If she pointed to that sentence, one of the many sentences in Wojnarowicz’s pieces that detail the rage of living with AIDS as a queer person, if she read it to her child, what would that have done? What conversations might she have had beyond the discourse that this is a clock, that is a flower, these, David, are pieces of art?

There’s no mothers or children at the exhibition of Wojnarowicz’s installations on display over at P·P·O·W. The gallery, situated as it is on the far corners of the west side, near the piers where Wojnarowicz once cruised, though now in 2018 they’re nothing like the piers Wojnarowicz once cruised. The Chelsea piers in this present day are littered with cutesy white families on the lawns picnicking, white gay men jogging, and the white European tourists taking hundreds of selfies with the polluted Hudson. The piers today are rather tomb-like. Few people share the space with me as I walk through the various installations. Map-collaged skulls of animals, a papier-mâché head covered with newspaper clippings on the Catholic Church’s positions on AIDS, and a short film where Wojnarowicz plays an abusive head of household are displayed across the gallery. The varying politics and themes Wojnarowicz conjured throughout his oeuvre, the failings of the United States on behalf of minoritized peoples, homophobia, the hypocrisy of the Catholic Church, and the attention to mortality and death, are manifest.

In The Lazaretto: An Installation About the Current Status of the AIDS Crisis, an installation first displayed in 1990, the importance of the textual and the visual once again emerges. Macabre in style, the installation is a mazelike experience, walls made of black trash bags with white posters in black marker presenting testimonies of people living with AIDS. In the center of the installation is a TV that shows footage taken from the first time the installation was presented, and on the surrounding walls are statistics on AIDS. The installation in 2018 is a condensed version of the one presented in 1990, missing several components featured in the original, like Yvonne’s room. Yvonne’s room, based on collaborator Paul Marcus’s experience working with a young Hispanic woman named Yvonne, displayed a bedroom with a decomposing body lying on a bed, pill bottles and garbage thrown around her. Text, written in what appears to be blood, is on the walls, detailing the injustices done to minoritized peoples by government officials. Governmental negligence—the disposability of deviant bodies—is front and center within Lazaretto.

The statistics on AIDS, the scrawl in blood on the walls, and the testimonies lining the black trash-bag walls, among other textual elements, once again combine the textual and the visual. The viewer must contend with the fact that the installation, as medium, and art, as genre, are indistinguishable from the statistic, the report, the testimony. The art of AIDS is the art of text is the art of the statistic. The realities these kinds of facts and truths hail are inseparable from, inextricable from, and, as Wojnarowicz highlights, constitutive of the process of making art and the intention of art when it reaches its final form. In turn, the statistic must be reckoned with in aesthetic judgment, as a component of the art, unavoidably present. Taken from its typical context of grudging realism—the report on the CDC’s website, a PowerPoint presentation from a professor of sociology, the five o’clock news—the statistic, as number and text, is placed within the domain of art in Lazaretto. There in the installation, now as art, the statistic becomes unfamiliar, perhaps more shocking, more appalling, more enticing than it would be if encountered on a website, in a classroom, a report, a tweet. The statistic eats away at the sensibility of those who expect their art to behave in the abstract, the conceptual, the disembodied, the depoliticized, the art for Art’s sake. The art of the statistic is sublime in its horrifyingly mundane, grotesquely ordinary, presentation.

I lose track of the mother and child towards the middle of the exhibition at the Whitney. The pieces I dwell over are saturated in the politics of AIDS and queerness, saturated in a visuality and textuality that cannot be simplified and commodified into one word, a pointed-finger naming. Three photographs on the white wall depict artist, and friend of Wojnarowicz, Peter Hujar a few hours after dying from AIDS. The first is a shot of his face. The mouth is open, cheeks gaunt and exasperated, a sideways glance with lifeless eyes. A face with nothing left to suffer over. The second photograph is of his hands. The nails discolored, the fingers loose, unflexed, untightened, at last in peace. The final shot is of his feet. Thin and bony, somehow emaciated, as if telling us even the feet cannot escape the impact of AIDS, its ravage, its cruelty, its lonesomeness. AIDS is unavoidable in these photographs, its politics inescapable, irreducible to a pointed-finger naming. A finger aimed at naming and classifying that would be unable to articulate the queer activism of Wojnarowicz, ACT UP, and Hujar, the ashes of loved ones who died from AIDS being thrown on the White House lawn or the die-ins in St. Patrick’s Cathedral, the long days and even longer nights of AIDS activism through the decades fighting for queers to live, to love, to fuck, to exist in our fabulous excess. No finger-pointed naming, so particular a gesture as it is, belonging to the white mother, to the innocence of the white child’s knowing, could do this historical labor.

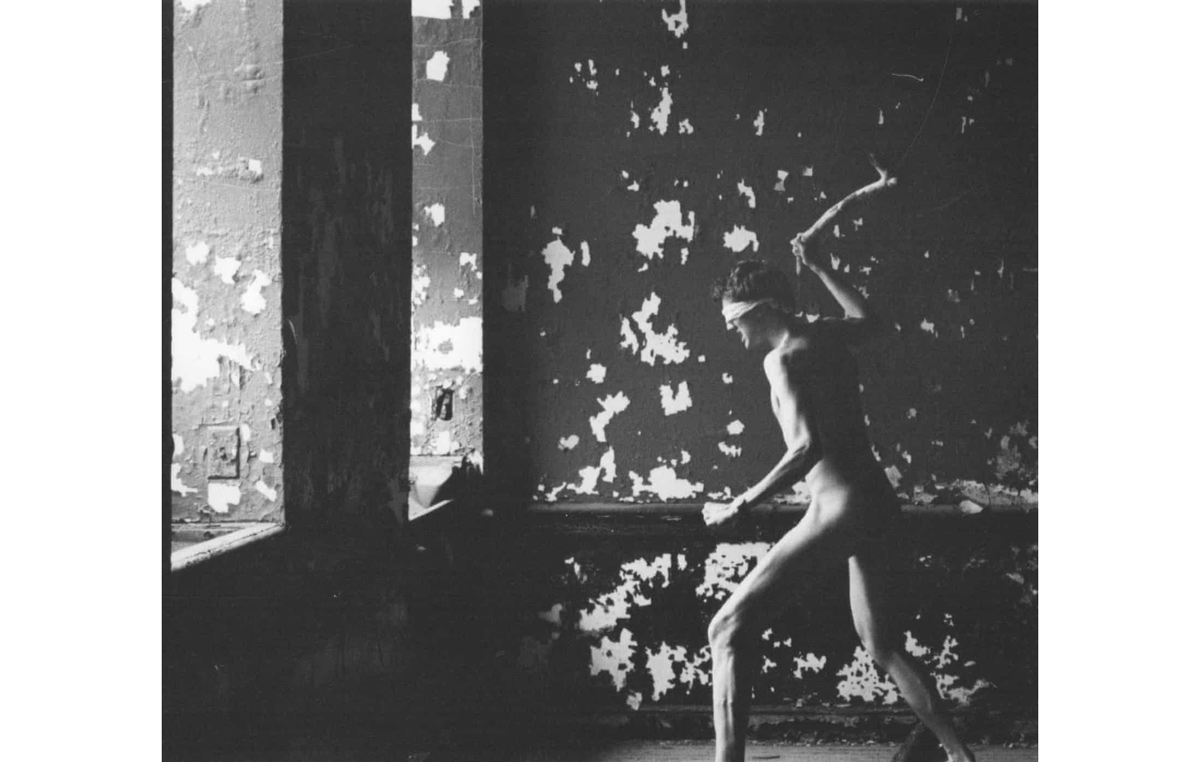

Is this the art of AIDS? The sublime that is disease and queerness? The sensory inexplicable, which Wojnarowicz captures in many of his surreal-like, hallucinogenic paintings, and even his writings. “The center is something outside of what we know as visual, more a sensation,” he writes in his essay “Being Queer in America,” where a page-length associative listing of grotesque items follows. The “huge fat clockwork of civilizations” and the “malfunctioning cannonball filled with bone and gristle and gearwheels and knives and bullets and animals rotting with skeletal remains and pistons and smokestacks pump-pumping cinders and lightning and shreds of flesh.” These extended syntactical flourishes tinged with violence are pervasive in his writings, and this is the result of the vision he sees “beneath the tiniest gesture of wiping one’s lips after a meal or observing a traffic light.” Wojnarowicz’s sensibility allows the most inconsequential, the most mundane movement to simultaneously contract and expand in meanings, across time and space, real and unreal, executed with a crisp attention to lines, shadows, colors, hue, and other elements of painting. Essays like “Being Queer in America: A Journal of Disintegration” and “In The Shadow of the American Dream: Soon All This Will Be Picturesque Ruins” demonstrate how the writer is artist, tuned in to the visual and the meticulousness of details, into the everyday surreal that transforms how we engage with the real conditions of human life like AIDS, being queer, homelessness, fighting to survive.

I stand there for a while before the photographs of Peter Hujar. I lose track of the mother and child, of the guards nearby, the other gallery viewers in their hustled pace taking photographs of every piece then promptly moving on. You could say I am contemplating what I am seeing, lost in thought there before the body dead from AIDS. This body I call mine is stiff, the facial features taut and tight, posing like this before the body dead from AIDS. I have no thoughts. I am but body, the organs and the cells and the flesh stirring, processing the images and texts entering my eyes. My tío died from AIDS, or, as his obituary states, “his illness,” but no one took pictures of his dead corpse, his diseased and queer body, his lifeless Puerto Rican cadaver. No one thought it artful enough to do so. No one thought it important enough to have a photo of a corpse on display in a family album so someone like me, a queer child like me, could point with my finger and ask what happened to my tío, what did he die from, who did he love? No one thought anybody would want to see that.

There I am in this moment framed by whiteness. Not the whiteness present within Wojnarowicz’s work, which he accounts for in his writings and artwork. Rather, it’s the unaccounted-for whiteness, the whiteness language can barely articulate, the language of whiteness something we are not supposed to articulate. The whiteness that is the nuclear family, the white child and the white mother, their white innocence that is the pointing, the expensive stroller, the one-word identifiers, the cooing voices, the authoritative steps in the art-gallery space. The whiteness that is being able to point and to name, to classify and to reduce, to know and to simplify because that is how opposition, queerness, resistance, deviance is subdued, tolerated, incorporated within the parameters of the oh so liberal, oh so progressive whiteness contained within middle- and upper-class America. The whiteness that is the art-gallery space that has catered to the bourgeois interests of white people, white culture, and white supremacy from time immemorial, where good taste and aesthetic judgment meet high culture, where whiteness has instituted itself as the whiteness we have known for so long. Yet, paradoxically, the whiteness of the gallery space is infiltrated by the whiteness of the white nuclear family. How to account for this? This whiteness against whiteness? And me standing there, this queer of color, this queer trying to grapple with AIDS in the moment Wojnarowicz is creating, in this current moment I find myself in? My body there immobilized between this whiteness clashing against whiteness?

The child crosses a line of black tape placed in front of a painting. A guard takes a step forward, hesitates, and looks at the mother alarmed. The mother, thankfully, notices this and says, “Look, David, look at the painting. Isn’t it pretty?”