As the Republican tax bill, which President Trump signed into law on December 22, wound its way through the legislative process, Congressional negotiators backtracked on a number of provisions that would have been devastating for higher education. The original version of the tax bill passed by the House, for example, included provisions that would have taxed graduate-student tuition waivers and eliminated the Lifetime Learning Credit, but these provisions were cut from the final bill as the House and Senate versions were merged. Whereas the original bills generated a great deal of concern—not to mention nationwide protests—the removal of these provisions gave way to the strange sort of coverage into which partisan politics tends to congeal, and as such we find the Washington Post calling the final bill “good for graduate students and university employees” but “not so good” for colleges. (Remaining in place are certain provisions that would, for example, tax some college endowments, limit philanthropic donations, and possibly lead to cuts to state funding.)

Higher-education reporting can helpfully run the numbers and calculate “winners and losers” in a bill like this. But it often has trouble explaining the crisis of higher education and how things got to this point. The tax bill, after all, is only the latest move in a much longer history of restructuring that began decades ago. After so many years of rising tuition and declining state funding, it is worth taking a step back and mapping out the current state of higher education in order to clarify what the future could hold. For this sort of analysis, we need to look away from the twists and turns of partisan politics, however mesmerizing, and start somewhere else.

Just a few days after the Senate passed its version of the tax bill, the credit rating agency Moody’s released a report revising its outlook for the higher-education sector from “stable” to “negative.” The higher-education press framed this story primarily in relation to the tax bill, but the report’s implications go far beyond the proposed changes to federal policy. Its key finding is that, over the next 12 to 18 months, revenues will grow more slowly than expenses, especially though not strictly at public institutions. “The annual change in aggregate operating revenue for four-year colleges and universities will soften to about 3.5% and will not keep pace with expense growth, which we expect to be almost 4.0%.” The report goes through every revenue stream—student tuition, state appropriations, research funding, patient care, endowments, and gifts—and finds that in nearly every case growth will decline.

These days, tuition is the most important revenue stream for colleges and universities. Tuition at both public and private colleges and universities has been rising for decades, at a much higher rate than inflation. Skyrocketing tuition helps account for the fact that student debt in the U.S., currently valued at over $1.3 trillion, has overtaken all other sources of consumer debt besides mortgages. Rising tuition has also generated a backlash, not only by students and families, who are increasingly reluctant to pay (which would commonly require them to go into tens of thousands of dollars of debt), but also by politicians, who have responded by implementing tuition freezes or ceilings. It probably also contributed to the return of the culture wars during the Trump campaign by reinforcing the narrative of academia as “elitist” and “out of touch.”

The usual story about tuition hikes goes something like this: As state governments have cut funding for higher education, public colleges and universities have raised tuition to make up for these budget cuts. University administrators like this story because it allows them to wash their hands of responsibility, blaming politicians (especially Republicans) for leaving them no choice but to take such action. But this story gets some important things wrong. For example, it can’t explain why private universities—which aren’t subject to the same funding pressures from states—have raised their tuition at similar rates over the same period. Most importantly, however, the usual story gets this history exactly backwards. As Chris Newfield explains in his new book The Great Mistake, “Tuition hikes preceded and were independent of the most serious cuts. Public colleges and universities raised tuition about 50 percent during the 1980s in constant dollars and another 38 percent in the 1990s, when real state funding actually increased slightly.” How, then, do we explain rising tuition?

A better explanation focuses on the restricted or unrestricted quality of different revenue streams. In very broad strokes, colleges and universities have four main revenue streams: state appropriations, research funding, gifts and endowments, and student tuition. The first three come with serious restrictions regarding their use. Generally speaking, state appropriations can only be used for educational expenses, research funding is largely spent on specific research projects, and endowments go toward the pet projects of wealthy donors. Only student tuition can be used for anything university administrators want—construction projects, real estate, interest payments, administrative salaries, football coaches. In recent decades, university administrators have sought, like all entrepreneurial institutions, to maximize their revenues, but they have sought above all to maximize their unrestricted revenues—and have even been willing to sacrifice state funding in order to bring in more tuition. And as Newfield observes, as administrators made tuition increasingly central in their budgets, state governments have been more and more willing to cut university funding.

What the Moody’s report highlights, to return to the matter at hand, is that things have changed in a crucial way: We have hit a tuition limit. Although administrators may be reluctant to admit it, students and families are less and less willing to pay ever increasing tuition bills, in spite of the so-called “wage premium” a college degree continues to confer. The tuition limit is not some absolute number, and we are certainly not claiming that tuition will not continue to rise past a given level. Rather, the tuition limit names a trend by which, after growing rapidly over the past few decades, the rate of increase in tuition has begun to decline. This trend is visible in enrollment numbers, which have declined consistently since 2011; in the politicization of tuition hikes, which has led many state governments to freeze or limit tuition growth in recent years; and in the cases of a number of schools making headlines by slashing tuition in an effort to compete for price-averse students. “Affordability remains a primary area of focus, with a market that is increasingly sensitive to higher education’s price versus perceived value,” states the Moody’s report. “Public universities will have lower growth in net tuition revenue, 2%-3%, as they face increasing political constraints, including state limits on raising tuition.”

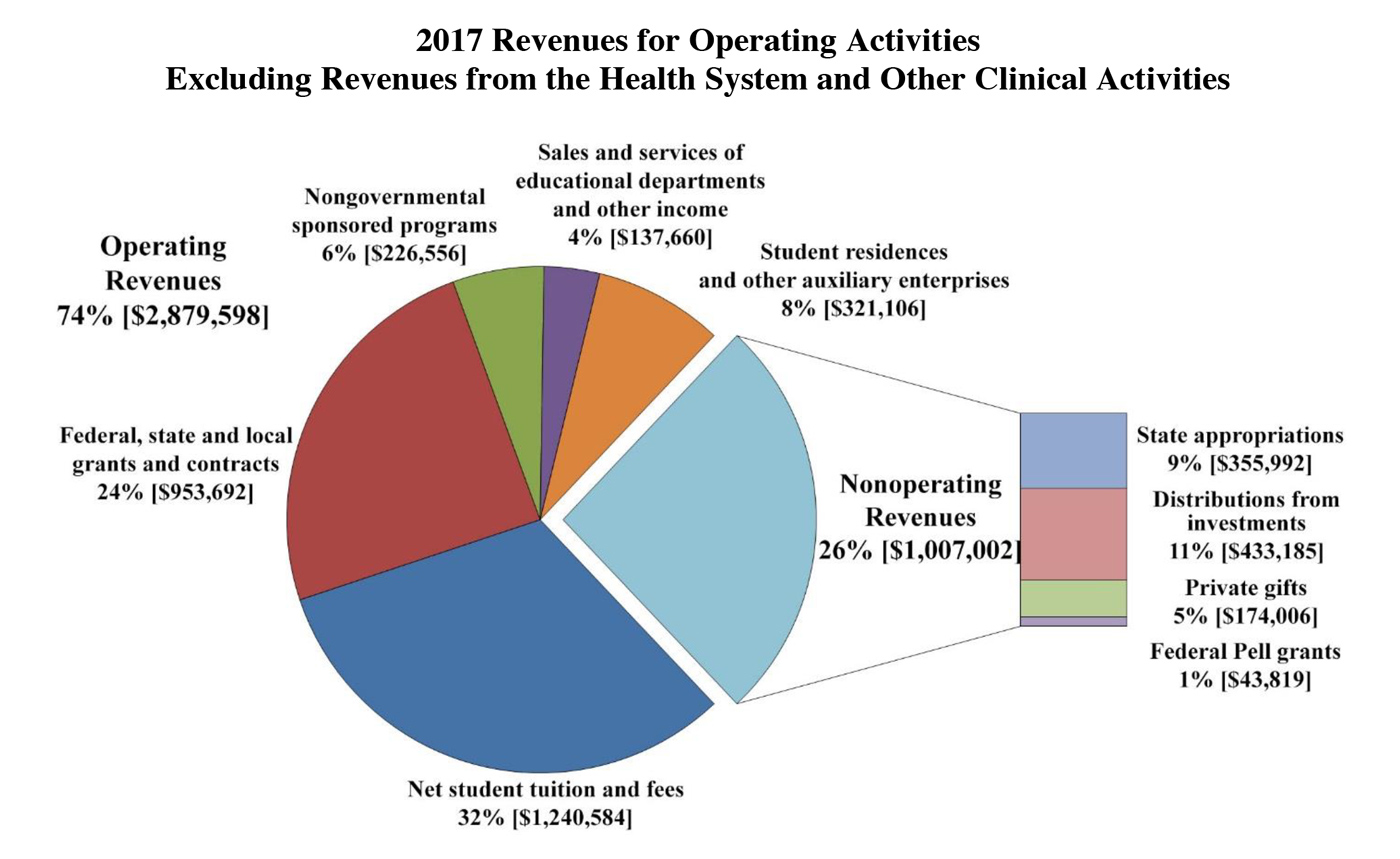

The tuition limit will have enormous consequences for higher education, though they may be slow to unfold. It will sharpen the ongoing crisis and intensify competition throughout the sector. Colleges and universities will attempt to turn to other revenue sources to replace what has until now promised unending growth in unrestricted dollars. The problem is that no other revenue source runs as deep or offers as much flexibility as tuition did during the golden age of tuition hikes. Consider the operating budget of the University of Michigan, which is often treated as a model for (public) research universities.

Breaking down these numbers, we find that net tuition and fees—net as in after financial aid has been taken out—brings in about $1.2 billion, nearly one-third of the university’s budget; and research funding from governmental and nongovernmental sources combined, another $1.2 billion. The other two main revenue flows generate nowhere near this amount: Distributions from investments, or what the massive endowment contributes to the actual running of the university, accounts for $433 million, or 11 percent of the budget; and state appropriations for $356 million, just 9 percent of the budget. The only revenue stream that seems capable of matching tuition is research funding, but research is not a growth strategy, because it can be used only to support particular research projects (and some of the overhead that such projects require). Moreover, Newfield’s work shows that research funding in fact acts as a drain on university resources, since grants only support part of the costs. For their part, endowments and state appropriations lag far behind the two biggest revenue sources, and the Moody’s report projects that both will slow in the coming years, with “weaker investment performance in fiscal 2018 and 2019, which could add pressure to endowment spending” and higher education budgets extremely “vulnerable to reductions as states prioritize their spending.”

What all of this means is that the higher-education sector, which is facing, at all levels, a tuition limit, appears to be entering a period of sustained crisis. From the vantage point of the present, we see at least four possible trends and responses to this crisis that we imagine will intensify in the coming years.

First, universities will attempt to restructure their revenue streams. These attempts will for the most part be unsuccessful, for the reasons we explained above. It is instructive to look at the case of UC Berkeley, which recently released a new, “revenue-driven” budget in an attempt to deal with a $150 million budget deficit. (Of course, new revenue streams would be paired with budget cuts.) During a presentation to the academic senate last November, the chancellor outlined six revenue streams that would be emphasized under the plan: “non-degree enrollment (such as UC Berkeley extension or summer sessions), self-supporting degree programs, increased contract and grant activity, increased entrepreneurial activity, monetization of real estate and philanthropy.” More tuition, more research grants, more philanthropy—there’s little untapped potential here. Furthermore, the possibilities for growth in these areas are extremely limited, and such efforts will confront universities with a series of even more difficult choices, like whether to dramatically cut health-care and labor costs and how best to force competing institutions out of the industry in order to position themselves more favorably in the search for student enrollment and state and federal aid.

Second, faced with these difficulties in reshaping revenue streams, universities will begin to compete on price, something the industry has resisted while increased student debt loads have been able to circumvent, for a time and to some extent, the effects of skyrocketing tuition. There is already some evidence that is happening in the out-of-state student market. A recent article found significant cuts in tuition prices at smaller universities and colleges in North Carolina, but also notes that lower tuition prices did not lower school revenues, meaning that institutions were cutting aid offered at the same time. However, as this example illustrates, competing on price by lowering tuition runs the risks of exacerbating rather than solving the revenue problem. What this suggests is that the era of price competition will be complicated and potentially bloody. Smaller schools and institutions with high debt loads will be forced to cut first, and one can imagine a scenario where larger institutions try to wait out the price war until enough competitors go under. While it is unclear how price competition will play out, one result will certainly be the intensification of already existing racial and economic disparities, as racial minorities are disproportionally served by for-profit institutions and smaller community colleges.

Third, as a consequence of these processes the sector will be subject to a wave of school failures, closings, and mergers. In 2015, Moody’s predicted that the rate of closure of small colleges and universities would triple by the end of 2017. While that prediction has not been borne out, closures are up significantly in both the for-profit and nonprofit sectors. Between 2015-2016 and 2016-2017, the number of aid-eligible institutions in the United States—one way of measuring the total number of college and university closures—fell by 5.6 percent, the fourth straight year of decline. This trend seems poised to continue, making the only question how rapidly closures and mergers will accelerate. On a political and discursive level, an important part of this process will be a debate over the extent to which these closures are the result of excess capacity (measured either in terms of the number of institutions nationally or compared with the available student body). Both the centrist/liberal press and right-wing think tanks have begun to advance arguments that there are simply “too many colleges” and that there has been a “massive public overinvestment” in higher education.

What these kinds of arguments leave out is that the crisis of university enrollments was created not by overinvestment but by price increases at many times the rate of inflation and the requirement to take on massive debt loads to access these institutions. It is not difficult to imagine that if college were free, classrooms would be overflowing, as the problem for many students is not a desire to attend but a means. Arguments about the need to reduce the number and size of universities will play a part in naturalizing the coming “new normal” of higher education as an elite or upper-middle-class activity. Furthermore, debates over excess capacity will be particularly important for the way they dovetail with the educational agendas of hard-line conservative and/or techno-libertarians to push students into technical, manufacturing, or health-care training programs or to “disrupt” or “unbundle” the university by replacing it with professional or technical certificates. The “fact” of excess capacity will have many potential uses.

Fourth, as the crisis of higher education intensifies over the coming years, the kinds of crisis-based experimentation reflected in the recent tax-bill negotiations will intensify as well, remaking the university in ways that today we can barely begin to imagine. The crisis will give a toehold to the most extreme, fringe ideas about how best to “disrupt” higher education—the disastrous 2012 wave of MOOCs and online education will seem tame in comparison to the “solutions” that will be rolled out as more and more parts of the system are put into play. Whatever form they might take, these “disruptions” will most likely find traction in a part of the system fighting for survival and from there spread outward. They will “succeed” as long as the administrators who created this crisis and the unsustainable model of debt-financed education into which it has congealed remain in power and no alternative social force—other than those of far-right disruption—emerges to confront the coming revenue crisis and debt crunch.

To those wishing to resist such transformations, the battle will clearly be an uphill one. Still, there are certain opportunities to be found, for example, in the fact that as profit margins narrow, so too will managers’ room for error, maneuver, and cooptation. This means that campus-based struggles by students and workers—whether through recognized unions or voluntary associations—could be able to exercise greater leverage on administrations and perhaps put additional elements of the system into play. Any such struggles, of course, will require a great deal of organizing, but they could also force an expanded conversation about what a truly autonomous university might look like. As the very idea of the university as a social institution of mass democracy comes under attack, those on the left will have to name for themselves a future university or infrastructure of education and knowledge production worth fighting for.