Wow, at the BRIC Arts & Media House in Brooklyn Jan. 30 through Feb. 1, retells the tale of Milli Vanilli's rise and fall as multimedia opera

“For the sign to be pure, it has to duplicate itself: it is the duplication of the sign that destroys its meaning.”

—Jean Baudrillard, Simulations

I’ve listened to Milli Vanilli more than any other music I own. Girl You Know It’s True was released when I was 11, and in those intervening years of adolescent unselfconsciousness I played it so often, the ink on the cassette dissolved and the tape inside warped from wear. I could always identify it in my collection because it was the one that was completely clear.

Director David Levine has contributed greatly to the ennoblement of this fact with his newest work, Wow, an opera based on the brief and deceptive musical life of the world’s most famous lip-synchers. (After a CD skipped during a televised "live" concert performance in 1989, the band's career began its precipitous decline, culminating in 27 lawsuits against the performers and the label for consumer fraud.) Created in collaboration with composer Joe Diebes and poet Christian Hawkey, Wow is being performed at Brooklyn’s BRIC Arts & Media House as a work-in-progress. I spoke with David about our mutual interest in the band and the cultural forces that both produced and destroyed it.

MIKE THOMSEN: It always struck me as strange that we can't accept the idea of a front person as a symbolic, emotional conduit. A violinist in an opera is basically just emoting someone else’s work. But the sort of emoting Milli Vanilli did, arguably no less persuasive or important, was unacceptable because it had no classical skill behind it.

DAVID LEVINE: It’s an interesting parallel; it’s not one we’d discussed explicitly. The Faust thing was pretty clear from the get-go. We were talking about Wagner and his inescapability in opera, and Die Meistersinger von Nürnberg, being the least “Wagnerian” of his works, is really about that — not only the composition of the perfect popular song but also the mastery of formula. There are all these formulas you have to follow to write a master song — it’s not about genius, it’s about your ability to play within the rules. The metaphor is built into Wagner’s opera.

It comes up a lot in various late 19th century anti-Semitic discussions of musical performance, that Jews could be great interpreters but they couldn’t be good composers, they couldn’t do anything primary. Once that role of interpreter gets written into our scale of genius, it’s interesting what happens.

We try not to resolve the question of who’s more of a genius, the composer or the performer, but there’s a space for instrumentalists to move between interpretative and creative roles. Yet there’s no allotted space for a master lip-syncher to do that, so we implicitly say it’s not valid.

But you have to ask why. These guys were incredibly convincing performers and very talented lip synchers. If your body is your instrument, we believe you have creative skill if you can speak. Sound winds up being the determinant. Are you or are you not producing sound? If you’re not producing sound, then you’re out.

That distinction between being responsible for making sound versus feeling seems to highlight a rooted shame in the audience. Awareness of how an emotion is produced makes us kind of ashamed at how susceptible we are to manipulation. It’s interesting to note where we’ll allow ourselves to be vulnerable and where we won’t.

We can watch America’s Next Top Model and go through this hyper-articulate evaluation of what makes someone a good model. You wouldn’t call that highbrow, but it’s tolerable in a way that lip-synching isn’t. But with Milli Vanilli, there really was something essential in Rob and Fab — they were a perfect conduit to bring out qualities in the music that wouldn’t have been detectable without them.

That’s especially true of rock and pop, and the role of frontman or lead singer. We assume it’s a relationship of equivalence: I am moved by this because I assume you, the singer, are moved by this. That can go from Rihanna all the way to the Dead Boys. I’m going to assume Stiv Bators is going through some shit, that’s why he sings that way. It’s not just a dumb pop relation, it’s a basic rock relation. I think there’s a threefold shame. One is being caught, two is being exposed as being dumb, and three is being seen as just a tool.

But how much more exquisite could the Stooges have been if they’d been lip-synced by Fab, and Iggy had only recorded the vocals? How limited have we been by this equation of the voice with the frontman?

Rob and Fab made their own style. We think about them in terms of the production of affect and what made them so unique—European pop and German pop, especially in the 1980s, is deeply perplexing. You think of how much of it is homegrown from there, how much of it is imported from America, and the idea of what a pop star should look like in the first place. The logic that holds these braids, these jackets, these biker shorts, these shoes — the notion of doubling, which seems totally unnecessary — this youthfulness, this effeminacy, this machismo. The only thing that holds it together are these two guys wearing it all, but you’re trying to figure out under what logic all these things make sense together, and you have no access to it.

I just don’t know who Milli Vanilli were legible to. You watch their live performances and they are studs. You can get away with not seeing it because they were also so girlish, but in concert they’re crotch grabbing in biker shorts. But they’re also wearing halter tops. All of which is to say, it’s such an exquisitely unlocated look that can take you in so many different directions. Legibility looks so monotonous beside it.

Looking back, there’s a continuity with what Frank Farian, the impresario behind Milli Vanilli, did with Boney M., taking another pastiche of West Caribbean singers, doing these electro-fied disco tunes of traditional folkish songs like “Rasputin” or “Rivers of Babylon,” and selling it to a primarily white, German audience. It reminds me of music I heard from the Danish side of my family and the pop aesthetics that come out of socialism, this à la carte plucking of cultural affects from around the world, scraping away history and context, and preserving only the most superficial affects for an audience that believed it had solved their historical problems and retreated into a tiny little bubble.

That’s one of the things that’s so weird about it. Milli appeared post–Michael Jackson and Run-DMC on MTV, and it was just at the start of MTV Raps, so there was still this weird uncertainty about race and aesthetics. I feel like there was this golden age of German and Scandinavian bands on MTV, like A-Ha, Falco, Nena, Golden Earring — and after Milli Vanilli that was just wiped out. Milli Vanilli were pop musicians who were held up to operatic standards, in a way. There is this need in music to have at least some tiny, original kernel of creativity coming from inside the performer, otherwise the whole structure makes no sense.

It destroys the foundation of music as a consumable good. There’s a sense of scarcity and specialization underneath vocal ability and playing instruments that supports the notion of music as worth paying for, but when you’re just buying enthusiasm, the whole commercial market starts to seem like a farce, like you’re paying for something that you could probably do just as well on your own. Which reveals how nauseatingly passive being a music fan actually is.

That’s interesting — what I thought you were going to say was one of the things that was so excruciating about Milli Vanilli was that they revealed that spectatorship had always been more active. We go to venues and pay money because we want the act, but the band was really just a veil. And on one side of it is the means of musical production, and on the other side are the consumers; and actually, we’re kissing each other through the veil. All this time we thought of ourselves as just receiving, just consuming!

Thinking of yourself as a passive spectators is a way of reducing your own complicity. If you really dream of an active spectatorship, you have to face up to the fact you may have been active the whole time, deep-kissing this industry. And then you have to ask that same question of every frontman. Was it all just this artificial kiss?

The framing of the whole performance almost as a critical-essay format, with a narrator guiding the audience both through the technical procedures and also analyzing the plot as it unfolds — it creates a comforting sense of deconstruction around the whole thing: The audience can offload the work of judging to the narrator and go a little further out in actually sympathizing with Rob and Fab.

Yeah. I tend to be super-mistrustful of relying on symbolism or silence in staging things, I think it can be really inefficient. It’s not necessarily like the audience would have condemned them as villains, but it’s the funny thing about having a narrator, especially a casual narrator because she’s mostly ad-libbing from this general structure on the iPad she carries with her. If we had presented the story in a statelier and more distanced way, it would have become an allegory and implied our repudiation of them as characters. We wanted to create a much more intimate, supportive, and less haughty relationship between the spectacle and its protagonists.

If you’ve got a casually critical, essayistic narrator weaving the whole thing together — which you’d think would increase the distance and formality — it actually does the opposite by knitting everything together through familiarity. I think it goes back to spectator ethics and relationships. You — the audience — can get the high-culture, experimental kind of experience if you just hang out in that first room, which is very cold and very '80s, early '90s avant-garde performance art. Or you can go to these other rooms and see these tawdry, kind of tongue-in-cheek pop stunts performed. So the internal opposition between opera and pop gets played out spatially. You can be one kind of audience or the other, and the narrator becomes a bridge between those two.

The performance moves through a lot of different rooms in the theater and breaks down a lot of the traditional structures separating performers and audience. I kept wondering if I was consuming it in the right way. When the crowd moves en masse from one side of the room to the other, or when they all follow the performers into the hallway or foyer — you’re also able to stay behind and keep watching through a video feed. There’s a poetic sort of stress about where to go for the authentic experience.

Early on, I was like zero-degree artifice, let’s just use the spaces as they are. We decided there was no point to trying to make the space look like anything other than what it is. They have a weird rehearsal studio — I’m sure Rob and Fab used a rehearsal studio. They had an art gallery — one of their videos is set in an art gallery. They had stadium seating in one area — we decided to do a stadium scene.

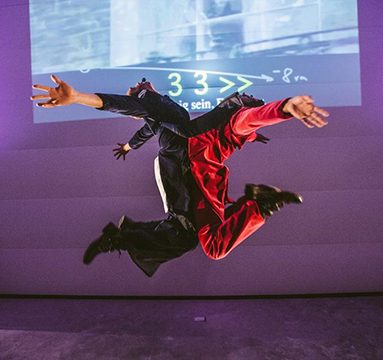

We talked a lot about having scenes alternate between talking and lip synching. We knew it was going to start very close to dance, and as it went on it would get closer and closer to opera. But the idea was that since you could always see the performance actually being produced or generated, it would move through all these instantiations. Opera as backup music for dancing. Opera as two-channel audio installation. Opera as big performance moment. Opera as press conference. Opera relies on having the kind of stage you can throw things at.

One of the things we could try out was experimenting with different spectator behaviors in different settings: How do you behave when you’re in a gallery? How do you behave when you’re in a hallway? How do you behave at the opera? How do you behave at a shitty downtown studio? It reveals the conditions of your spectatorship — what makes you watch in a certain way. Opera really kind of encourages one kind of fandom and discourages another, because it disavows its own relationship with camp. One thing we really wanted to do with this was to test opera and its relationship to how its produced, its relationship to virtuosity, to genius, its relationship to history.

What I like about that first room is there’s so much you could be watching. You could be watching the score, you could be watching the orchestra, you could be watching the singers, you could be watching the lip-syncing dancers who play Rob and Fab, you could be watching the video being projected on the wall—which is all stuff shot on site, intercut with Milli Vanilli videos. But what we noticed was that if we didn’t insist on watching any particular thing, people would always favor following the lip-synchers out of the room instead of watching the production of sound.

And that should, if anything, absolve Rob and Fab, because we set it up so that you can choose: You knew going in it was fake, and you still chose to follow those guys. You can have your cake and eat it too, but it turns out you don’t actually want to have your cake. You just want to eat it.