Why do we think of the kleptomaniac as being usually a woman, and why do we find her so alluring?

Blithe (“It amuses me”), yet shockingly honest (“I am a plain downright thief”), this confession places her in a cadre of some of literature's most fascinating characters — real and fictional — who indulge an impulse most of us resist. Compulsion, by definition, makes for a fascinating read: A compulsive character must inevitably be vested with extraordinary desire – that “alchemical agent,” as Jonathan Franzen nicely terms it, “by which fiction transmutes my secret envy or my ordinary dislike of ‘bad’ people into sympathy.” Yet this desire in many ways mirrors the reader's own desire, stretched, as it were, to an uncomfortable extreme, so that we find ourselves perhaps cringing from this character’s behavior while at the same time oddly rooting for it. MacLane's memoir, offering legions of young women the opportunity to see a visceral and uncensored version of themselves in her depictions, became an instant sensation.

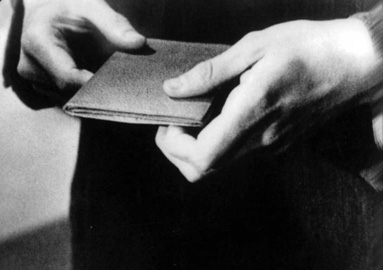

More than a hundred years after MacLane, Jennifer Egan opened A Visit from the Goon Squad with Sasha, one of the novel's protagonists, eyeing an untended bag in a public restroom. In it, barely visible, lay a pale green wallet. “It was easy for Sasha to recognize, looking back, that the peeing woman's blind trust had provoked her,” Egan writes. “It made her want to teach the woman a lesson. But this wish only camouflaged the deeper feeling Sasha always had: that fat, tender wallet, offering itself to her hand — it seemed so dull, so life-as-usual to just leave it there.” The appeal for Sasha isn't the monetary value of the wallet or the contents inside. She seizes it out of an arbitrary need; the wallet could just as easily have been something else. In her home, Sasha keeps a pile of the other objects she's stolen over the years. Random, trite, useless, these include a screwdriver, bath salts, binoculars, pens, keys, and a child's scarf.

This wish to acquire for the sake of acquiring, and not out of need or necessity, is of course markedly different from the way in which Daniel Defoe's Moll Flanders, perhaps the most celebrated female thief of the written word, starts out. Left to fend for herself after her husband dies and leaves her penniless, Moll is wandering in the street one night when she spots an untended package. Tempted by the sight, she believes the Devil placed it there in order to bait her into a life of crime: “'Twas like a Voice spoken to me over my Shoulder, ‘Take the Bundle; be quick; do it this Moment.’” To her “horror,” Moll finds herself taking it. Yet Moll continues to steal even after her financial situation improves. “I cast off all remorse and repentance,” she assures us, before boasting: “I grew the greatest Artist of my time.” And so it happens that the first modern English novel also features the first shoplifting heroine whose penchant for making off with “Flanders lace” gains her notoriety— as well as a new surname. You can’t steal, Defoe implies, without stealing becoming an intrinsic part of your identity.

The psychoanalyst Melanie Klein explained this impulse to take what doesn’t belong to us as incubating in childhood. The drive plays out in children's fears of the “burglar under the bed,” which, Klein claimed, partly emanate from the “child's own fears of their own desires to break into their mother's body.” And feminist readings have, over the years, laid claim to the act of stealing as the weak’s rightful appropriation of what they’ve been denied: In 1987, the scholar Alicia Ostriker suggested that “women writers have always tried to steal the language” because, throughout history, a woman “had to state her self-definitions in code form, disguising passion as piety, rebellion as obedience.”

Like Moll Flanders, the first real-life trial of a shoplifter also involved lace, when, in England, in 1800, a discerning store-owner caught a gentlewoman stepping out with more of the pretty threadwork than she’d paid for. The criminal was none other than Jane Leigh Perrot, the well-connected aunt of Jane Austen, whose social status helped her land a swift acquittal. A few years after her famous trial, however, Leigh Perrot was spotted leaving a gardening shop carrying a secreted plant. Her lawyer later confessed that, in his opinion, “Mrs. L.P. was a kleptomaniac.” The lenience granted to Leigh Perrot wasn’t unusual. The courts of both Victorian England and Gilded Age America consistently allowed upper-middle class offenders to walk free while working-class criminals were imprisoned, and often hanged, for the same transgressions. In 1896, the anarchist Emma Goldman denounced this phenomenon in a speech. The law of “Thou Shalt not Steal,” she argued, had “come to be applied only to a certain class.” The distinction? “If a rich woman is caught shoplifting the wealthy court has a new word for her and says she is afflicted with 'kleptomania' and pities her.”

***

Kleptomania, or, as it was initially called, klopemania (borrowing from the Greek words for stealing and insanity), was coined in 1816 by André Matthey, a Swiss doctor who defined it as both a “desire for theft” and “theft without need.” In her brilliant 2011 book The Steal, which provides an exhaustively researched historical survey of the culture of shoplifting, Rachel Shteir documents how the term has since evolved: In the mid-19th century, kleptomania was linked to melancholy and observed to be accompanied by a sense of dread; around the same time, with the construction in France of the first department stores, kleptomania came to be viewed primarily as a women's disease — a reputation it hasn't been able to shirk since. The female shoplifter, Shteir writes, became known in those years as “the madwoman in the store”— one who is “forced” into stealing by the temptations of the modern world.

Kleptomaniacs proliferated in books of the period, including Emile Zola's 1883 novel, The Ladies' Paradise, in which he writes, of Madame de Boves: “She stole for the pleasure of stealing, as one loves for the pleasure of loving, goaded on by desire.” According to Shteir, the rise of criminal anthropology toward the end of the 19th century codified the notion that kleptomaniacs “were born to steal.” The term was further elaborated by Freud's disciples, who traced the condition to female sexual repression. Wilhelm Stekel, a former protégé of Freud who was later disparaged by his mentor (“Stekel is going his own way”), wrote in a controversial 1910 essay titled The Sexual Root of Kleptomania that the disorder was caused by “ungratified sexual instinct.” Later, with the onset of World War I, Shteir notes that kleptomania underwent yet another revolution, with psychoanalysts moving away from an examination of its sexual roots, and instead explaining it as “the behavior of traumatized groups.” Compulsive stealing came to be seen as the acting out of mass trauma; at times it was equated — quite literally — with the period's frenzied territorial conquest.

Over time, the connection between kleptomania and sexual repression dissipated. When the American Psychiatric Association published its first listing of mental disorders (known as the DSM) in 1952, kleptomania wasn't even included. By the 1970s, it was no longer treated as a disorder but as an ideology: The hip, rebellious (typically male) shoplifter had been invented — both in real life and on the page.

Consider, for example, Augie March, Saul Bellow's drifter protagonist, who makes a point of stealing only books. “It was a big Jowett's Plato that I took,” he explains. “But I was severe with myself to finish the experiment. I checked the book in a dime locker of the Illinois Central station ... and immediately went after another, and then I made good progress and became quite cool about it.” As if to prove a moral high ground, he adds: “It never entered my mind to branch out and steal other stuff as well.” There’s also a book-lifter in Roberto Bolaño's Savage Detectives. (“One of the inconveniences of stealing books — especially for a novice like myself — is that sometimes you have to take what you can get.”) To this day, the book-lifter is often seen as a romantic sub-species of the kleptomaniac: he doesn't steal so much as reclaim what rightfully belongs to the people. Note the unequivocal “he.” Unlike the “madwoman in the store” cliché, the book-lifter, as well as, it turns out, the writers whose books are being stolen, is predominantly male.

***

But if the radical book-lifter is primarily male, is it true that the kleptomaniac is mostly female? Look into almost any definition of the disorder and you’ll usually find some variation of the following distinction: “more common among women.” Just as women are more susceptible to have body dysmorphia or to become compulsive buyers, so the thinking goes, they are also more prone to develop an uncontrollable impulse to steal. Shteir theorizes that “people who feel excluded in one way or another are most likely to steal.” Yet the slipperiness of the boundary between stealing and shoplifting, and between shoplifting and kleptomania, also attests to a possible gender bias: Why do we call a woman who repeatedly steals a kleptomaniac but call a man who does a serial thief? Why are we so quick to internalize the woman’s transgression but externalize the man’s?

Though popular culture often conflates kleptomaniacs and shoplifters, clinically there has been an attempt to distinguish between them: Most estimates suggest that the former group represents only between 0-8 percent of the latter. The shame and embarrassment associated with the disorder, however, could mean that the numbers are actually much higher. In fact, kleptomania does not only go untreated in many cases, but there's also no consensus among experts on just how to treat it. While antidepressants are known to help some kleptomaniacs, the results are not definitive. In many cases, kleptomania is linked to a host of other mental illnesses, such as bipolar and anxiety disorders, eating disorders, depression, or substance abuse. Finding a cure for the disorder has long been considered impossible.

I remember sitting glued to the television after news broke of Winona Ryder's shoplifting scandal. Here was an actress at the top of her career, reduced to snipping tags off Dolce & Gabbana handbags, and caught leaving a Saks Fifth Avenue store carrying six different bags she hadn't paid for. Other celebrities who have reportedly sought a five-finger discount: Lindsay Lohan, Britney Spears, Farrah Fawcett, and tennis star Jennifer Capriati. It’s hard to read about these stories and not wonder why. Why would someone willingly court public shame, and risk losing everything, for a $15 ring or some makeup from Target? There's no way of really knowing. (Buckling under outsized pressures may offer one answer.)

This air of mystery may be precisely what draws writers to examine kleptomania in the first place, and to imprint it, as a kind of scarlet letter, onto their fictional characters. But kleptomania also represents something else: Merriam-Webster defines it as “a persistent neurotic impulse to steal especially without economic motive.” According to medical dictionaries, it is an impulse control disorder that “involves the theft of objects that are seemingly worthless.” In other words, kleptomania represents the risk associated with stealing, minus the gain. The triviality of the objects that attract the kleptomaniac — their worthlessness, in short — can be seen as reflecting the kleptomaniac’s own sense of self-worthlessness. Indeed, the disorder presents writers with the perfect pathetic fallacy: What better way to signal to readers that a character deems herself without any value than to have her pocket things that are valueless, too? And what better hatchet to wield at society's excesses than someone who can't seem to ever get enough? The kleptomaniac is the nemesis of Robin Hood: She steals for purely selfish reasons, and yet her sense of self is already diminished. Which leads to kleptomania’s curious inner conflict between an utter insecurity on the one hand, and a disproportionate sense of entitlement on the other. Kleptomaniacs may suffer from low self-esteem, but, as the psychoanalyst Adam Phillips tells Shteir, they also see themselves as ultimately “stealing something that belongs to them.”

In an essay for The New Yorker, Miranda July, graceful chronicler of all things awkward, describes her own past dabbling with shoplifting — a skill at which she became increasingly good. “I discovered that stealing required a loose, casual energy, a sort of oneness with the environment, like surfing or horse-whispering. And once I knew I could do it I felt strangely obliged to. I remember feeling guilty for not stealing, as though I were wasting money.” Strangely obliged to. July’s passive tone, her sense of cordial behavior, is reminiscent of Sasha in The Goon Squad trying to “teach the woman a lesson.” Unlike the ideological shoplifter of Steal This Book, the kleptomaniac does not think of herself as subverting social order. Rather, she believes herself to be acting on society's behalf — like an outsider trying at all costs to fit in. Think of Allison in The Breakfast Club, the epitome of an outcast if ever there was one, who disappears a wallet, a knife and a lock off a locker, before undergoing an almost too-perfect makeover. (“Yeah, I always carry this much shit in my bag. You never know when you may have to jam.”)

These women appear calculated, even rational, in their compulsive stealing. There’s inner logic to the chaos of the objects they take, and ease to their method of operation, which exudes a certain grace under pressure. As Egan writes of Sasha’s stealing: “Her bony hands were spastic at most things, but she was good at this – made for it, she often thought, in the first drifty moments after lifting something.” Ironically, by being classified as kleptomaniacs, society deems these women erratic, sick, and therefore ultimately irresponsible for their actions. There’s a compassionate pardoning in this social gesture, but also an implicit condescension: Men who steal belong behind bars, we seem to be saying. But women? They can’t control themselves. They’re irrational. Literature, of course, shows us that, at its root, the impulse to steal is anything but irrational. (“I have only two stipulations,” MacLane coolly analyzes her penchant, “that the person to whom it belongs does not need it pressingly, and that there is not the smallest chance of being found out.”) What continues to puzzle readers about kleptomania, then, seems to be not the act but the triteness — the lingering gap between its high stakes and low rewards. And in that gap also lies its elusive appeal. Sasha, overcome by a desire to take a screwdriver for which she has no need, feels herself “contract” around it “in a single yawn of appetite.” The object is of course insignificant, but the reader takes Egan’s cue and imbues it with meaning. Pointlessness, after all, has a certain beauty.