This is the editorial note to The New Inquiry Magazine, Vol. 21: Witches. View the full table of contents here.

Subscribe to TNI for $2 and get Witches (as well as free access to our archive of back issues) today.

***

A French pamphlet called “The Rioter and the Witch,” composed in the wake of the 2005 unrest, reminds us that “like every magic ritual, a riot is a fleeting moment of perception of the invisible.” The opposite is equally true: Every magic ritual is a fleeting moment of perception of the invisible riot. Which is to say the witch is also an Amazon, a figure of female war.

The war continues. Silvia Federici, in Caliban and the Witch, pointed out the thread linking the witch and her sisters, “the heretic, the healer, the disobedient wife, the woman who dared to live alone, the obeah woman who poisoned the master’s food and inspired the slaves to revolt,” to the grand sorcerer, capital. Though the witching hour of history may have passed, there is always the promise of another midnight.

In a male-supremacist society, female power must logically appear illogical, mysterious, intimate, threatening. “Witch” stands for all those unnamable shadow acts of disappearance and withdrawal, self-cultivation and self-medication, that elude the social and sexual order.

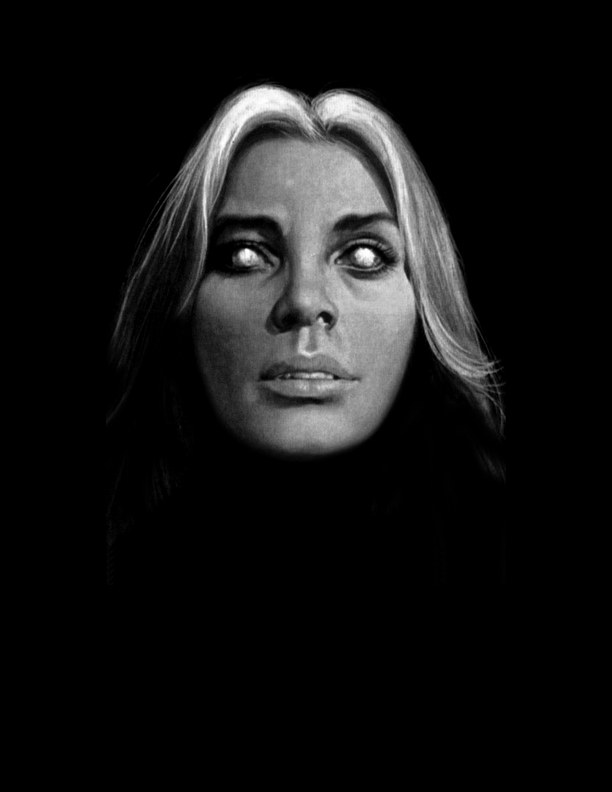

In serving as an effigy of everything that must burn, the witch takes on a dizzying number of meanings: She is action at a distance and she is an addict; she is ambition or enchantment but also incantation and melancholic attachment; she is both a Mercedes Elegance and artisanal production. She is beauty itself, and she is left over. She is resourceful, cunning, practical, and she stands for excess, obscenity, and repetition compulsion. She is female friendship and solidarity, but also inscrutable solitude, banishment, and exile. She is a succubus but a withered crone. She is such a woman that she isn’t.

These days, of course, safely banished, the witch pops up again deep in domesticity: kitchen magic, beauty magic, bedroom magic, parenting magic. Autumn Whitefield-Madrano finds kinship with witchcraft in the word glamour, with its etymological links to both grammar and grimoire, and the rules beauty magazines lay down for the occult arts of physical charm. Durga Chew-Bose sees spells demoted to success recipes in Nicole Kidman’s Hollywood witch vehicles, Practical Magic and Bewitched. Whether brazen or calculating, her witches pour their power into snagging men and modern housewares—on credit, no less.

Domesticity isn’t solely the social control of women, though. Through the domestic, women can also assert control over the social. The hearth is her harp before even becoming hausfrau. Christine Baumgarthuber traces slumber-party covens back to virginal rites of man-trap baking in Hex Before Marriage. And Fiona Duncan collects an oral history of The Craft, and of our adolescent ardor for four outcast girls who transform the slights of high school into Wiccan supremacy. Moira Weigel watches women in China hunted and punished as shengnü, a name for “leftover women” that originated in horror stories of maidens melting into bone-white crones. Colin Dickey acquaints us with Montague Summers, the last great defender of Europe’s witch hunts.

Black magic also now finds a home in the gray market. Witches in today’s economy bill their clients for medical or financial consultation, albeit unlicensed and vernacular. Alireza Doostdar discovers that in Iran, nothing limits one upwardly-aspirant Tehrani witch, whose penned grimoires take cues from self-help classic The Secret in order to satisfy government-backed dreams of social mobility. Nic Cavell writes of Witch House, the circa-2010 music genre that “made a subject of the Internet’s emotional implications.” And Karla Cornejo Villavicencio outlines how botanicas—the community pharmacies, repositories of syncretic Christianity, and primary-care facilities for some of the 50 million Latinos who live in the U.S.—will be impacted by Obamacare. Botanicas’ popularity “points to the failure of the church to properly provide for its own, highlighting its postcolonial fractures,” she writes.

Is magic a route to the radical imagination, or simply a shortcut to conventional acquisitions, commercial and domestic? What separates the witch’s foretelling from the capitalist’s risk analysis, her spellbinding from public relations? “Are you a good witch, or a bad witch?”

But ultimately it’s beside the point to question the morality of a witch’s existence. A witch summons hidden forces to castrate the social order, poison the hearth, and fly above her “natural” station. She presides over irrepressible antagonisms, drawing on the bottomless caldron of resistance. Her power is real.