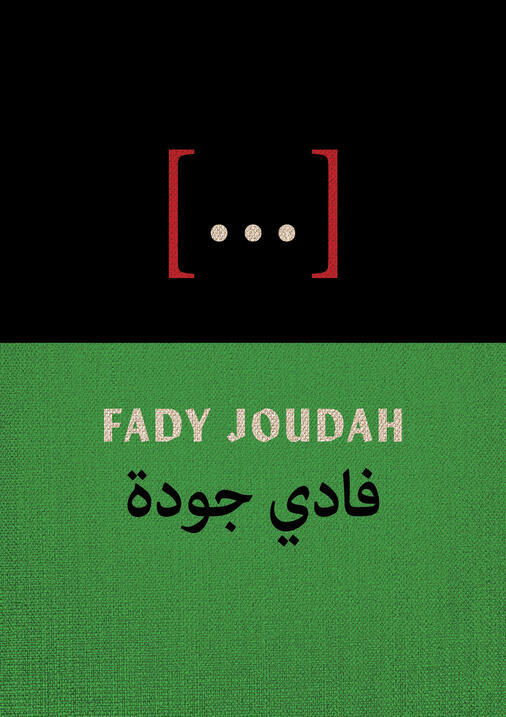

Fady Joudah’s poems are exquisite yet ungovernable, rebelliously innovative yet attuned to a broad range of traditions. They spoke to me long before I had the pleasure of meeting their author or the honor to call him a friend. I have worked with Fady as an editor on several occasions, saving our exchanges—both in my files and in my mind—as private lessons not only in the verbal arts he and I both practice, but also in the art of conducting oneself in the world with uncompromising dignity. His latest collection, […], was composed over three brutal months of Israel’s war on the Palestinians of Gaza, but it is far more than a record of brutality. Fady’s responses to my questions below indicate the richness of the poems he has given us and of the humanity they mourn and celebrate. - Boris

BORIS DRALYUK: If I were to isolate the most prominent device in these poems, it would be repetition. And the use of that device in itself seems a statement. None of this is new, the forms of these poems remind us. None of this is news. And yet each repetition is marked by a subtle change that often carries radical implications. The voice of these poems knows that “[r]epetition won’t guarantee wisdom,” yet it does repeat “cease now,” knowing—or hoping—that each context is different. You and I have corresponded and checked in on each other often, over the years, when history repeats itself. How do you manage to remain undefeated by historic repetition? And what can poetic repetition offer us?

FADY JOUDAH: There is no life without repetition, beginning at the molecular, even particle level. There is no art without life. To remain viable, art, inseparable from the circularity of the human condition, also repeats. What is a life without memory? And what is memory if not repetition. But not all repetition guarantees what we call progress, a euphemism for wisdom. Repetition with reproducible results, for example, is a foundational concept of the scientific method. Yet science can be an instrument for the destruction of life as for its preservation. This suggests to me that repetition in art is our unconscious memory at work: art mimics the repetition of the life force within us. All art is a translation of life. Take Jackson Pollock’s so-called action painting. What is it if not a rhythm of a life force in all of us? In those paintings, the pattern is recognizable yet unnamable. It’s like watching electrons bounce off each other. The canvas contains entropy. We understand this at a cellular or quantum level.

But what of Palestinian art? What repetition in it do we reject or turn away from, and why? What of Samia Halabi’s work that the state of Indiana prohibited from being shown? What of Suleiman Mansour’s life in art? Does Israel destroy art in Gaza or steal it as well? And how many Palmyras did Israel destroy in Gaza? The Church of Saint Porphyrius. The Omari mosque. These, too, are questions of repetition. It bears repeating that love is a human right. Yet we have far less access to love as such than most of us are willing to admit.

Some of these poems take the form of a dialogue with or an apostrophe to the “aggressor.” One begins, “You, who remove me from my house.” At the start of another, the speaker suggests, “Why don’t you denounce / what you ask me to denounce. / We can do it together on the count of three.” There is, in this dialogue, a great deal of pain, but there is also humor and understanding, or at least an attempt to understand. The speaker urges the “aggressor” to “[l]isten,” even promises to “lick [their] ears against revenge.” Do you believe the attempt to understand can ever be mutual? Are these poems, at least in part, an expression of hope that it can be?

“Aggressors also grieve,” I write in another poem in […].Yes, understanding is not meaningful if it happens in a void. It must involve others, and requires touch. The timing of understanding is another story. When will I understand you, as you need me to understand you? How long will it take? Will you subjugate me through this process or will you rise toward equality? This is why humor is necessary, because one of the marks of totalitarianism or fascism is the erosion of humor. To what extent is the US totalitarian in its foreign affairs? Does the US have any capacity for self-deprecation vis-à-vis Palestine? What might that sound like?

The only humor available to extreme oppression is in dehumanizing others they’d like to dominate, eradicate. Of course, this is not humor. It is pathologic deception and sadism. For me, the capacity to laugh at oneself and at one’s oppressor is to leave a window open for understanding. It is an offering I make. A hope, as you say. Hope as a life force, a force of eros, not a death force.

Zionism has no sense of humor left, if it had any to begin with. All it has left to stand on two legs is radical violence, preemptive and reactionary destruction. The Palestinian American comedian Sammy Obeid insists on humor in dark times. Palestine is all over his set. His humor breaks taboos. The laughter makes us kinder as we feel simultaneously daring, liberated, if momentarily. Extremism, on the other hand, is unimaginatively vulgar.

It is impossible to ignore the double erasure figured by the title of the book and of many of its individual poems: an ellipsis, bracketed. I can fill in the blank with any number of words, but the blankness appears to be the point. “Daily you wake up to the killing of my people,” you write, and then ask, “Do you?” Could you speak about the silence, or the silencing, the title indicates?

Once I begin to speak about the silence that remains, it is no longer a silence. My translation work on Ghassan Zaqtan’s selected poems, The Silence that Remains, honors this. “I am not your translator” is another line in […]. It is an echo of Baldwin’s “I am not your Negro.” As a Palestinian in English, I am not a cultural bridge between the vanquisher and the vanquished. Perhaps […], too, is an exercise in listening. Listening to the Palestinian in English does not mean that the Palestinian is always talking. We also need to learn how to listen in silence to the Palestinian in their silence. So far, when a Palestinian goes silent, it means they are dead or violable, digestible, liable for further erasure or dispossession. English has not begun imagining the Palestinian speaking, let alone understanding Palestinian silence.

Speaking of an exercise in listening, one of the longer poems in the book is a sequence of ten maqams, “I Seem as If I Am.” As I understand it, the maqam is a system of microtonal musical scales not easily annotated using Western models. To learn the scales, one must listen and listen. Your poem, too, insists on our listening; few lines, even the most aphoristic, deliver the entirety of their meanings in isolation. Enjambment and recontextualized refrains unlock layers upon layers of nuance. One line, however, is too aphoristic not to quote: “A free heart within a caged chest is free.” I have long stood in awe of your ability to defend the freedom of your heart, despite all attempts, even well-intentioned ones, to cage it. Could you speak about the maqam as a form, and perhaps of the role it has played in helping your heart remain free?

So, “maqam” also means a place of standing, a position of being, whether social, historical, or spiritual, physical or metaphysical. A maqam is also where the departed have stood, have established their presence, and have compelled us to commemorate them. What these meanings share with music is a conversation with and a journey through time. The music rises, descends, pauses, between the note and the scale, the singular and the plural. It positions itself in relation to the performer and the audience. And repeats.

Ultimately, a musical maqam aspires to “Tarab,” a word that lacks an equivalent in English and other Western European languages. Tarab is the state of ecstasy, even if sorrowful, that one reaches through music or song. The concept exists in all cultures, of course. But in Arabic, this sensorial arrival, concurrently a departure, has a specific word. In the maqams in […], I aim to correspond with Arabo-Islamic concepts as art and not as didacticism or hoary exoticism. Stereotyping is nothing other than a dead language, which may lend itself to the death of what and whom it speaks. “Barzakh,” for example, is a very complex concept. It has been discussed for centuries. I am not compelled to explain it. Instead, I join the conversation through art. The same for the maqam poems. “Maqam for a Green Silence” does not need to explain Moses’s encounter with al-Khidr. And no Wikipedia page will suffice.

One of the poems in this book shares a title with an earlier poem of yours, from Alight (2013). In that first poem titled “Mimesis,” the speaker’s daughter rejects his advice to tear down the web of a spider that prevents her from taking her bike out for a ride. “She said that’s how others,” the speaker reports, “Become refugees isn’t it?” In this new iteration of “Mimesis,” an “inch-long baby frog” enters the speaker’s home “during the extermination / of human animals live on TV.” In another poem in this volume, the speaker predicts that his deceased diabetic dog will be reincarnated “as a person who can’t afford their insulin.” Could you reflect for us on the relationship between the human and the animal in your poems? Has your training and experience as a physician affected your view of that relationship?

One doesn’t need to be a physician to understand what it means to be unable to afford insulin. Our relationship to animals and other creatures is one of dominance. So that when they are our best friends or the recipients of our magnanimity, we are still in control, and they are our subject and metaphor. It is immense not to kill a spider out of empathy for the displaced. And yet how many spiders have we killed since that poem. I wanted to counter the popularity of the first “Mimesis” with the second one. I wanted to ask questions about the empathy of convenience, the silken kingdom of eureka. “Eureka” itself was a pronouncement of the law of displacement. The displacement of others activates empathy until genocide exposes that empathy for what it had been all along: an idea. Still, I respect that idea when it takes root in the heart.

Did our capacity and willingness to exterminate species coincide with our practice of genocide? Probably not. It took a while for the two to go hand in hand. Arguably, the so-called modern age began with the extermination of mostly Arabs and Muslims, but also Jews, in Spain in the fifteenth and sixteenth centuries, and quickly took on the indigenous peoples of the Americas. Al-Andalus as a living civilization was decimated, erased, and whatever remained of it went into hiding, survived only in code.

By the late eighteenth century, the European colonial project began to exterminate other life forms along with humans. Now even water, a source of life, is systematically destroyed. It’s a good thing we can’t reach the sun.

We have gone from need as the mother of invention to invention as mother of need. And in surrendering to this way of life, we usher in catastrophe on a carousel, as if disaster is our only way out of our aporia, our Catch-22.

A physician holds power over the patient despite the patient’s bill of rights. I become a servant of the biopolitics of the state. Patients become my subjects, customers, etc. Our mutual humanity is governed by laws. Common decency doesn’t disappear but acquires an automated mode within the permissible machinations. On occasion, the same condition afflicts solidarity in social movements. Anyway, if the patient can’t afford insulin, it’s a question for the state to answer. If the patient receives a colonoscopy, it is not necessarily because humanity prevailed. Eventually, many patients with meagre means are referred to necropolitics, their new administrator in life. They are left to die without proper intervention from the state. They become collateral damage, and then their misfortune is, at best, transformed into an engine for change within civilization in peacetime. This says nothing of what happens in war, in genocide. Who bombs hospitals and inherits the earth?

The limitations of humankind… In some of the most haunting lines in […], the speaker describes the rescue of young girl from beneath the “manmade rubble,” whose rescuers momentarily make her feel “like a child / who lived for seven years above ground / receiving praise,” before the knowledge of “her family’s disappearance / sinks her.” You write, “All disasters are natural / including this one / because humans are natural.” There is no putting poetry aside, but it is only a side of your experience. Could you share with us how, since the beginning of this manmade natural disaster struck in Gaza, you have managed to live, day by day, as a Palestinian in this world?

I want to share but can’t. I live in America, a perpetrator of this genocide against me and the Palestinian people.

America is so well trained in parading the suffering of its vanquished. There is not enough acknowledgment in English of the debt owed to Palestinian sumud, resistance, survivance. Some solidarity with Palestine wouldn’t know what to do without Palestinians leading the way over and over again. In due time, we will look back at solidarity movements in the neo-imperial, multicultural age and see more clearly their perverse self-congratulatory aspects. Bread and bombs. Pills and prizes. In other words, there is a solidarity whose horizon is assimilation, and there is a solidarity whose horizon is liberation. The former is hierarchical to those it is in solidarity with. The latter is in community with them. The former treats them as abstraction. The latter is citational. It names those it loves.

Some of the most fascinating European minds of the 20th century were utterly blind to the plague of European colonialism and the people who were subjugated to it. Walter Benjamin and Hannah Arendt belonged to a persecuted minority, and perhaps the severity of their oppression limited their capacity to free themselves entirely from the viewpoint of their oppressors. Neither one could imagine the colonized people of the world. This is human, it can happen to anyone at any time, especially under duress. But this means that our age of solidarity has its own limitations, too.

Some expressions of solidarity in empire are fierce, led by “killjoys” who can share a laugh. Yet others feel too much like acts of self-assertion, flexing the power of the witness. This latter expression of solidarity seems tempered and vitiated by a superior moralism that panders to power through the critique of the victim. This activism is not rooted in generosity. It’s bewildering, I understand, to belong to a culture that believes that its capacity for repair is an eternal possession, granted by some providence. And look, they say, we have the historical markers to prove it. Now everyone wants to be witnessed witnessing. And so, my limitation in answering your question stems from a necessity to challenge the unrelenting audition that may or may not approve me as good material for a national product. A brand. A real competitor in the free market. The premise of this audition is false. I wonder, for example, whether the silence in […], and the foreign in that silence, are what we’re reflexively dismantling here, in the name of making the book available to a wider audience in the English that authorizes Palestinian annihilation.

What if I had no family in Gaza? Would you prefer to seek a more authentic Palestinian survivor? Who, among those in solidarity with Palestinians, imposes criteria of authenticity on the Palestinian in English?

I am far more concerned about the day after the livestreamed genocide of Palestinians stops. The day after is the longest day. And it is just as unspeakable.

A verse by Al-Mutanabbi from the tenth century: “Wretched are those who envy the wretched their lives./ There is a life worse than death.” Whatever happened to that girl’s smile? Has it returned to her face? Palestine in Arabic is always alive.