The disappearing work-life divide and the feminization of abstract labor in Sleeping Beauty

In the opening scene of Julia Leigh’s debut film Sleeping Beauty, Lucy (Emily Browning), our beautiful college-student protagonist, serves as a medical test subject. She leans her head back as the doctor slowly threads a tube down her throat, then fills a balloon in her chest with air while she holds the tube in place. Lucy cooperates excellently and leaves with an envelope of money and a smile.

Her still, submissive choking and gagging lend the scene a heavy erotic charge, an allusion to the sex work the viewer may already know is to come from reviews and trailers. In this first scene, Lucy is already selling her body; the distinction between this and prostitution is a symbolic technicality.

What’s most off-putting in this scene is Lucy’s ability to hold a smile on her face throughout the ordeal. If Lucy’s remaining still while holding the tube down her airway as her body jerks around isn’t work, then I don’t know what is.

Though she usually wears the uniform of an Anthropologie model and often seems to be doing not much at all — there are a few scenes of her cleaning up a coffee shop after working a closing shift and others of her biding her time in the copy room of the office where she’s an assistant — almost all of what we see Lucy do in the film is work. We know she’s working, but she hardly looks like a worker.

But what does a worker look like? Even the most traditional economic models, as well as revolutionary counter-currents, had to deal with changes over time in the character of what they called labor. In the Introduction to The Critique of Political Economy, Marx comments on Smith’s use of the term:

The indifference as to the particular kind of labor implies the existence of a highly developed aggregate of different species of concrete labor, none of which is any longer the predominant one. So do the most general abstractions commonly arise only where there is the highest concrete development, where one feature appears to be jointly possessed by many, and to be common to all. Then it cannot be thought of any longer in one particular form.

An undifferentiated worker isn’t just a farmer or a bricklayer or a Slurpee-machine mechanic, labor is a composite picture of different forms of human activity that we group under the term. But this aggregate isn’t stable, it exists in thought and appearance. What we come to understand as a general laborer is based on this “concrete development” of bodies in motion, but also on what Marx called the “preexisting abstraction”: the way we talk about labor in the first place. In this proudly contradictory formula, we tell the story of labor twice: first with our bodies, but only after we use our words. Sleeping Beauty is a film most of all about labor, what it means to work. The categories destabilize as the viewer begins to recognize what Lucy does with her time as work.

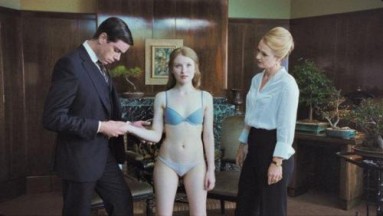

Despite her three paid jobs, Lucy still can’t make rent. This is what prompts Lucy to answer an ad in the school paper for a sort of catering gig: waiting on private parties while dressed in lingerie. She brings the same perfect submission to the interview that she showed in the first scene with the doctor. She lies about her drug use and submits to being poked and prodded by the madam Clara (Rachael Blake) and her assistant. It is her full body that is to be put to work, her full body that must be examined.

When Clara calls to tell Lucy that she’s been hired for some jobs, for which she’ll be paid exorbitantly, she cautions Lucy not to treat the income as stable. “Think of it as a windfall,” Clara says. “Pay off some student loans.”

There’s a remarkably open acknowledgment here that Lucy is in debt to a third party. The modern labor relation is not supposed to include employees’ consumer debt; whether they have credit cards is not the boss’s concern. A worker’s indebtedness is supposed to come up as a source of employer leverage only in shady criminal dealings when it’s owed to the boss: drugs and immigrant smuggling, or in the sharecropping fields and company towns we learn about in history class. But with student debt so prevalent, young workers are assumed (known) to have loans they’re compelled to pay, making them even more vulnerable on the market.

Unlike mortgage or credit-card debt, student debt is premised specifically on the value of the debtor’s body. The exorbitant size of U.S. college debt is justified by the students’ imagined future productivity; if you take out tens of thousands of dollars in loans for school, it’s because the debt will enable you to command enough on the labor market to pay it back. But when lots of workers need jobs, employers need any particular worker much less. In a sick twist, the known size of the general debt keeps wages down and young workers desperate, making their personal debt even harder to pay back, making them even more desperate, and so on until the wage goes literally negative in the form of unpaid internships. Sleeping Beauty dramatizes this debtor relationship: The old men who sleep with her might as well be the banks holding Lucy’s loans, taking payment in time with her flesh.

Lucy’s new boss tells her to maintain another dependable job, but which job could be dependable in the way Clara imagines? The cobbling together of part-time contracts leaves the precarious worker without any one thing to fall back on. Under earlier capitalist labor relations, workers’ ability to get another job gave them leverage on bosses to extract benefits. But under conditions of precarity, workers need more than one job to survive and to be constantly interviewing for new ones. Employers feel no responsibility to provide the means for workers to get what they need in order to live. With high unemployment and so much of job training moved to colleges, they’re easily replaceable.

This change affects workers’ ability to organize their lives around their jobs. The elements of the social democratic good-life fantasy — job security, health and retirement benefits, steady hours, a living wage, vacation, weekly nonwork time, among others — are available to fewer and fewer workers even as a realistic aspiration. These features are no longer even “common” (known) to all; many young workers now would have no idea how retirement or health benefits work, having never been offered them.

Not that we’ll need to learn. The precarious retort to the classic pro-union bumper sticker “The people who brought you the weekend” is “What the fuck is a weekend?” This insecurity is no longer an exceptional condition; it is a developed set of practices with features of its own. We still use the concept of undifferentiated labor, but precarious conditions come with different rules and different assumptions of what a generic worker can be expected to do. It’s more important that a worker know how not to ask for a raise, more desirable that she be adaptable than cutthroat. An employee without an office is always at work. The possibility that a worker might leave at some point due to pregnancy isn’t a drawback; it’s a good reason not to offer benefits or a path for advancement.

When we look at Lucy, we have a picture of the precarious subject: indebted, insecure, vulnerable. After a few successful nights as a server at parties for the rich, old, and distinguished, Clara asks Lucy to do a different kind of work. She’ll be put to sleep with a nontoxic drug, stripped naked, and left in a bed where men will pay to use her. Lucy will wake up with no memory of what happened, but the no-penetration rule will apply. She agrees.

These are the hardest scenes in the movie to stand. Watching the old men strip naked alone in a room with a beautiful young unconscious woman is disturbing enough. We peer beneath the tailored suits to their frames, either frail or bloated, but their dicks always recede into the shadows of impotence. These scenes lack the intersubjectivity of rape. One client just wants to snuggle with Lucy as he would with a giant doll. Another violently slaps her around in a sickening display. During this scene, viewers are acutely aware they are watching a beautiful young actress going through the exact experience depicted, except while conscious and on film. The physicality of these scenes breaks the movie’s narrative and exposes Browning’s acting as intensive labor. The flexibility that characterizes precarious work becomes literal, passing into limp. Lucy must be as flexible as a rag doll when a client throws her body around the room.

Clara’s firm assertion to Lucy that she won’t be vaginally penetrated plays with the viewer’s preconceived positions on prostitution, but also has a ring of truth to it. The combination of Craigslist personals, high debt, and the comparatively light stigma on paraphilic sex work has created a supply of mostly young women willing to freelance in the fetish business as long as it’s sufficiently distinguished symbolically from traditional prostitution. It’s certainly better paid than the medical testing, and less invasive.

It’s impossible to write about precarity without writing about gender because undifferentiated labor is reforming along these lines. Lucy’s passivity and her eagerness to please, her vulnerability and blank demeanor would look incredibly strange on a young man. Her willingness to keep treading water without the promise of anything better to come, her ability to communicate nonthreateningly and stay quiet at the right times are parts of what Nina Power describes in the chapter “The Feminization of Labor” in One Dimensional Woman:

All work has become women’s work, even that of men. No wonder the young professional woman beams down at us from real estate billboards as the paradigmatic image of achievement … At this point in economic time, those character traits [of precarious professionality] are remarkably feminine, which is why the pragmatic, enthusiastic professional woman is the symbol of the world or work as a whole.

Sometimes Lucy looks like she could be on one of those billboards, or at least the ones for community colleges, but the film is about the other times as well. It turns out the models in the pictures only own one set of clothing. Lucy persists and survives using what Lauren Berlant describes in her book on precarity, Cruel Optimism, as “durable norms of adaptation,” repeating the play of control and submission that characterizes precarity but under circumstances of her choosing. Whether Lucy is fucking guys at the bar based on the fall of a coin, taking drugs from strangers, or repeating ironic formalities (“And how are you miss?” “Oh very well, very well. And you sir?”) over glasses of vodka with a terminally self-destructive friend, she finds ways to make her being in the world sting less. Or the right amount. This is a nonrevolutionary enduring, a body’s holding together in a sea of dismembering tugs.

Sometimes Lucy looks like she could be on one of those billboards, or at least the ones for community colleges, but the film is about the other times as well. It turns out the models in the pictures only own one set of clothing. Lucy persists and survives using what Lauren Berlant describes in her book on precarity, Cruel Optimism, as “durable norms of adaptation,” repeating the play of control and submission that characterizes precarity but under circumstances of her choosing. Whether Lucy is fucking guys at the bar based on the fall of a coin, taking drugs from strangers, or repeating ironic formalities (“And how are you miss?” “Oh very well, very well. And you sir?”) over glasses of vodka with a terminally self-destructive friend, she finds ways to make her being in the world sting less. Or the right amount. This is a nonrevolutionary enduring, a body’s holding together in a sea of dismembering tugs.

Lucy shows she can endure, at least for now, but can she do more? Can the flexible resist?

If our conception of what it means to be a worker relies on having a bargaining place at the table with the boss — that is, with certain classical notion of workers’ power — then Lucy isn’t a worker. She isn’t a worker, even though all she ever does is work, as in the four stills from the film above. She’s not going to unionize her coffee shop, nor her fellow sex workers, nor the assistants at her office (from which she’s fired), nor the other medical subjects, and certainly not the students. If she tried, she’d be terminated or worse: Clara threatens her with vague but menacing consequences if she misbehaves. And what does the doctor care if she goes on strike? He’ll pay someone else and stick a tube down her throat. A strategy of resistance against precarious wage labor can’t be “unionize your Starbucks,” as valiantly as the Wobblies have tried.

I don’t know exactly what a successful strategy looks like, but I think it has something to do with the penultimate shot in Sleeping Beauty. Lucy wakes prematurely after a dangerous drug interaction to find an old man’s naked corpse in bed with her — a client who paid to die there. She opens her eyes with a kiss of CPR breathing from Clara, and sits up like the princess from whom the film draws its name.

She opens her eyes and she screams and she doesn’t stop.