My favorite social networks were Delicious and Google Reader. Delicious was a social bookmarking site. I saved links to pages I liked and by saving them I shared the links with my network, which had about seventy artists and writers interested in media theory and internet subcultures. We introduced each other to good reads, weird sites, and sharp jokes. Google Reader, the RSS feed aggregator, used to have a button that users could click to let friends see posts from blogs they followed. My Reader network was small. I had never met most of the seventy members of my Delicious network face to face, but I knew my five Reader friends well. We commented actively on each other's posts—an activity impossible on Delicious' comment-free interface. The networks were different but I liked both kinds of communication that they fostered. Delicious was a shared research tool, hive-like and impersonal. Reader was intimate but ephemeral. If I came across something of importance there, I would open it in a new tab and tag it for Delicious.

Late in the summer of 2011 my networks disappeared. Yahoo sold Delicious and the new owner's redesign deleted the connections. I saved my links but no one could see them. To promote its new social network, Google moved the share function to G+ while keeping the feed aggregator on Reader. I would have had to rebuild my network from scratch – and prune it – to keep it distinct from my G+ feed. It was too much work. The momentum was lost. The changes to Delicious and Google Reader were abrupt reminders that my favored modes of social interaction belonged to companies. In return for my agreement with the sites' terms of service I had used their services for free—until the terms changed.

Not long after my networks disappeared, Occupy Wall Street set up camp in Zuccotti Park. The site was a back-up plan. The organizers went there when they realized that barricading Wall St. would be impossible. Zuccotti Park is managed by Brookfield Office Properties, a commercial real-estate developer who took over Liberty Plaza, a public park, with a pledge to maintain it and extend its open hours around the clock. Liberty was switched out for the surname of John Zuccotti, a former City Planning Commission chairman and now the chairman of Brookfield—a man whose professional biography describes the muddling of public and private structure that became embodied in the park that bears his name. Zuccotti Park is an example of "privately owned public space," an arcane term from a zoning law coined in the 1960s that came to wider attention with the experience of Occupy. Occupy Wall Street and similar groups around the country could not set up camp in publicly owned spaces because of the curfews inscribed in old municipal laws. But they could legally make use of the privately owned public spaces that operate in the twenty-four hour regime of contemporary urban life and global capital. For two months, Occupy Wall Street lived in Zuccotti Park, engaged in dialogue and discussion, sharing opinions and information. In the end, Brookfield Office Properties colluded with the city government to eject the camp. We learned that the owners of privately owned public spaces can change the terms, and the public has no choice but to adapt. What happened at Zuccotti Park was not wholly unlike what had happened a few months earlier on Delicious and Google Reader, which, like any social media site, can be aptly described with a fifty-year-old term from zoning law: privately owned public space.

***

In the fall of 2011 David Horvitz was at Occupy protests in New York and Oakland. He tweeted from them.

Horvitz is an artist and a wanderer. The wandering is a part of his art, which tends to inhabit forms of travel and exchange. It is about the mobility of bodies and of data, and juxtaposes them to the stillness of contemplation.

His web site used to offer visitors a variety of transactions. Pay him $1,626, and he would go to Taketomi Island in Japan and mail you an envelope of sand. Pay him $1, and he would think about you for one minute; you could pay him to take the subway to a remote spot in New York and read Anna Karenina there. In these minor economies of attention, consumers got souvenirs—envelopes of sand, emails notifying you when he began and ended his minute's thinking about you—but they were merely slender traces of what the money had bought: Horvitz's time and the contemplation that had occupied it.

Horvitz's projects often straddle channels of information and geographic space. For Public Access he traveled up the California coast, stopping at public beaches to take photographs of himself gazing into the ocean. He uploaded the photographs to Wikimedia Commons, the database of images in the public domain that are used as illustrations on Wikipedia. The articles on California's public beaches were unillustrated, so Horvitz's photographs completed them. When members of Wikipedia's editorial community noticed that images had been simultaneously added to several articles from a single IP address – all featuring the same body facing the Pacific – they discussed the matter in the public forums. Was it an attempt to standardize images? Did the presence of the body make the photographs too personal for Wikipedia's community standards of “objective data?” Was it an art project? A prank? Some of Horvitz's images were removed from the commons. Others were cropped and kept: the body was removed, and only the water and sand remained.

Wikipedia is a privately owned public space. Its articles are managed and manicured as carefully as the flora of Zuccotti Park. Just as Wikipedia is groomed for smooth and sensible data retrieval, the privately owned public park is a place for white-collar workers to savor a moment of relaxation so they can return to the bustle of the office feeling refreshed. Zuccotti Park and Wikipedia both make sense in the framework of a neoliberal worldview that understands public spaces—in the city and online—as sites of discrete actions and transactions, as links in logical chains of cause and effect. They are not places so much as they are conduits of productive movement. Ersatz urban environments are built along this principle: the Silicon Valley offices of Google and Facebook eschew cubicles for plazas and promenades, in the belief that shared spaces of locomotion generate productivity and innovation.

But can public space be thought of in another way? Horvitz's images in Public Access depicted public beaches as spaces for doing nothing: for gazing into emptiness, contemplating or dreaming, open to glances of others and chance encounters with people and things. Deliberately or not, Wikipedia's volunteer editors rejected that idea of public space by deleting or cropping his images. They have no control over what people do on the beach, of course, but they can maintain their Commons as a channel for the clean and rapid harvesting of information, unimpeded by extraneous bodies and personalities.

Officials from New York's municipal government and police department will readily tell you that Zuccotti Park is available for protests and other forms of public speech—of course it is! But they must occupy a discrete period of time and be clear about their agenda. With triumphant spite, critics of Occupy pointed to the homeless at the camp as delegitimizing the occupation—as proof that the Zuccotti protesters were not members of a principled opposition, but vagrants and vermin. More than anything else, these criticisms revealed the understanding of space as a channel for motion, and the translatability of those terms into the realm of political speech. "Perhaps the best thing about Occupy Wall Street is its reluctance to make demands," Mackenzie Wark wrote in an early commentary. "What's left of pseudo-politics in the United States is full of demands. To reduce the debt, to cut taxes, to abolish regulations." While Wark does not draw an explicit connection, the spatial metaphor of the public sphere and the notion of demands and consequence has enveloped the role of public space in the urban environment. Occupy illuminates this through its inversion of the idea of the political movement. "An occupation is conceptually the opposite of a movement," Wark continues. "A movement aimed for some internal consistency within itself but used space just as a place to park its ranks. An occupation has no internal consistency in its ranks but chooses meaningful spaces which have significant resonance into the abstract terrain of symbolic geography."

Occupy's rejection of the familiar channels of activism is a mutant revival of medieval debates about the relative virtues of vita activa and vita contemplativa. Boris Groys invokes that dyad in an analysis of contemporary art and media culture, where he describes the proliferation of artworks that unfold in time—from film and video to durational performance—as an implicit affirmation of modernism's bias toward the active life. "The ideology of modernity—in all of its forms—was directed against contemplation, against spectatorship, against the passivity of the masses paralyzed by the spectacle of modern life," Groys writes. "Throughout modernity we can identify this conflict between passive consumption of mass culture and an activist opposition to it—political, aesthetic, or a mixture of the two." The paradox of film—that the moving image plays out before a spectator whose body remains still -—troubled Eisenstein, Brecht, and other directors of theater and film who wanted to agitate the viewer toward political action. Groys finds a resolution to this problem in contemporary art exhibitions which include so many hours of video works that the spectator feels relieved of the burden to take them all in, instead actively moving from one gallery to the next. Groys further relates display practices in art institutions to social media platformswhich encourage users to produce images and text. With the flair of exaggeration, he concludes: "If contemporary society is, therefore, still a society of spectacle, then it seems to be a spectacle without spectators."

Art can not only be active in form but also activist in orientation. The pseudo-academic conferences encountered at biennials and nonprofit art spaces continually pose the question: Does activist art affect social change? Does it make a difference to its phantom communities? The answer is always no. But the real problem is the question: it defeats itself when asked because it is hitched to the Newtonian gearwork of liberal democracy, the push-pull of the bourgeois public sphere as it emerged in the early modern age. As a cog in that mechanism, art can't change a thing.

Occupy Wall Street got caught in the American legal machine when it was forced to shift from an occupation to a struggle for the right to occupy. It moved to the channels of older social justice and civil rights movements: court actions against police and municipal authorities to defend the protesters' safety as they exercised their rights speech and assembly. This shift was accompanied by the sort of image production that Groys identified as the apotheosis of vita activa: the protests began to center around the documentation of police abuse and the circulation of these documents in social media—the staging of a spectacle for those who were making it.

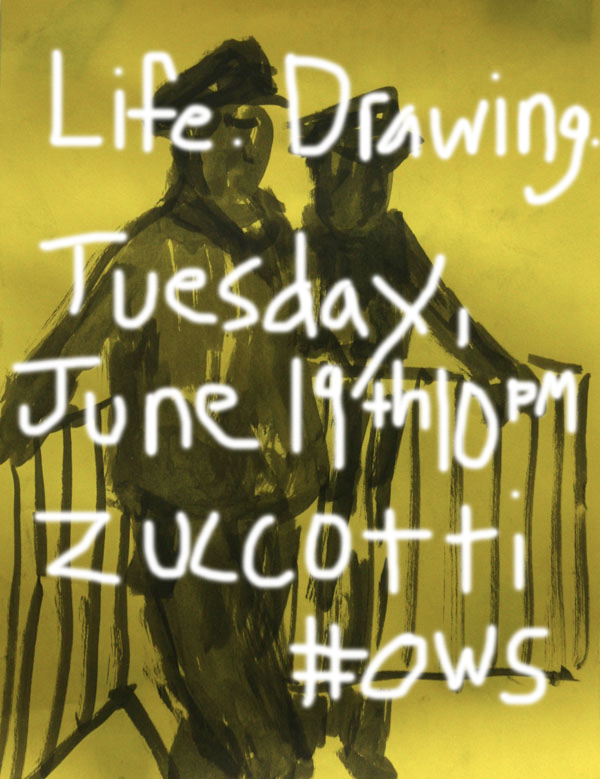

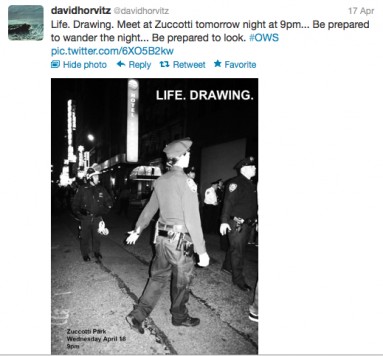

On April 17—seven months after Zuccotti Park was first occupied, five months after the camp was dispersed—David Horvitz tweeted: "Life. Drawing. Meet at Zuccotti tomorrow night at 9pm... Be prepared to wander the night... Be prepared to look." The group assembled, and with paper and colored pencils they observed the police presence in Zuccotti and drew it, working by streetlamps and studying the shadows to produce figure drawings of the police in the park. Life Drawing inverted protest activity by creating images that were not intended as documentation for immediate upload and circulation, but as a study of bodies in space. This involved viewing the policeman as an embodied subject rather than a mechanized apparatus in the system of struggle. Horvitz used Occupy as a wedge for rethinking forms of attention in public space. In doing so he found an aesthetic form for the occupation: a way of making images that openly eschews activism and embraces deliberative presence in public space.

***

Are the internet's privately owned public spaces available for contemplation? Or does the speed of information and the constant movement of data make that impossible? This summer a friend told me about how much he loved using his Kindle. "I always used to think reading was a waste of time," he said. "But now that I can highlight things on the Kindle and share them on my Amazon page, I feel like I'm actually doing something." His experience was different from my own. I am a student, and I read to accomplish the tasks assigned by a course syllabus. Sharing information—as I used to do with Delicious and Google Reader, and now do with Twitter—does not yield a feeling of "actually doing something." It is the weave of social being in the fabric of my everyday life.

Kevin Bewersdorf is an artist who theorized the internet as a space for spiritual mediation. His essays—recently collected and published as a free PDF by critic and curator Domenico Quaranta—consider the active mobility of digital images and the potential of the open space they occupy for contemplation.

Bewersdorf came of age as an artist about a decade ago, at the dawn of the Department of Homeland Security, social media, and the attendant anxiety over privacy and surveillance. One of his essays recounts his experience taking photos with his digital camera at a skate park, where an outraged mother demanded that he delete every photo of her son and the other boys. He insisted that he had no intention of exploiting the children and reminded her that they were in a public space and he had a right to make images there. "How dare you claim to have rights over a child!" the woman shrieked in reply. "This is exploitation of kids, and that makes you a bad human being." When public space is understood as a site of gainful, goal-oriented action, photographic images can only be made for a purpose, and that purpose is assumed to be surveillance and exposure.

Bewersdorf wonders what would have happened if he had set up an easel and made a realist painting of the children instead. "This woman would have certainly showered my painting with compliments," he writes. "Maybe she would have offered to buy it." He could have made the painting, too. As he reveals in another essay, he paid for his education by painting decorative murals. His last mural contract was at an asset management company where he was employed to bring a touch of Tuscany to the lunchroom where employees microwaved their leftovers. While taking a lunch break on the office park's lawn, he began to take photos of the building, "paying attention to the way the glass ark flattened itself with its own reflection." Until a pair of security guards pulled up in a van and stopped him. Bewersdorf was so disgusted by the corporate environment's aesthetic values—the esteem for painting, the fear of the digital image—that he decided never to paint again.

His frustration pushed him to articulate the spiritual qualities of the digital image on the internet. He divided internet users into two camps: INFObrats and INFOmonks. "INFObrats are on the web for obligations in their material and practical lives," he writes in a manifesto. "They shop, instant message, pay bills, relay practical data, and consume." INFOmonks pursue information for the sake of celebrating it, and share it for free. With a group of like-minded monks Bewersdorf started a group blog called Spirit Surfers. They posted found media artifacts and responses to these, removing the images from the flow of data and suspending them in the resonance of a diptych.

Bewersdorf is no longer online. If he is, he has cloaked himself in total anonymity. He removed his texts and images from his old portfolio site—as though the digital image had become too easy to understand and regulate as a commodity, and had begun to repulse him as much as painting—and visitors were redirected to purekev.com, a blue monochrome web page. The blue gradually faded away, until the visitor was gazing at nothing but a void of the browser's default white.

I won't valorize Bewersdorf's choice to disappear. I will criticize it, though I'm reluctant to do so. I know he won't read my words, and even if he does, his off-the-grid hermitage makes dialogue impossible. His work has worth; his spiritual vision of web surfing has influenced and inspired many other artists. But his radicalized understandings of action and contemplation, consumption and spirituality belong to a romantic mindset that has been easily appropriated by corporate mystification.

Consistency is for brands. A quest for purity makes you a product. I suspect that Bewersdorf became frustrated with the paradox inherent to his project and he decided his only way out was invisibility. But invisibility suits the marketplace fine. A good neoliberal subject is not online, he's just LinkedIn, moving smoothly through the channels of the marketplace without enough of a presence to disturb them. There is nothing outside those channels. The only way to oppose yourself to them is to resist the gainful movement within them. Horvitz is a good foil to Bewersdorf because he contaminates transactions with contemplations. He is brat and monk at once. He does not just use the digital image to pay homage to information—he puts his body inside it to record the relationship of information to the people who use it.

“Space” is a discourse of phenomena, the “public” is a discourse of politics. Private ownership is a discourse of economics that warps the others to accommodate the habits of using things and abstractions. It constructs protocols that make space and public as ephemeral as money. Communities can take shape around these protocols but they grow their own, unarticulated systems of interaction and affinity that change more subtly and unpredictably than terms of service and zoning laws. The latter are brittle. Communities—even the minimal communions that are established between two people, or between one person and an image or object of contemplation—adapt easily to new conditions, and thrive in discourses beyond those of the marketplace. There aren't enough terms of service to manage all the publics and space in the world, or the people who live in them.