Mortie is a darling girl. She never stops smiling. In her little yellow Mary Janes and her little yellow dress, Mortie is a little yellow speck of sunshine on any rainy day. She likes to go for strolls. We do not know where she comes from. We do not know where she goes. But under her big blue umbrella, perfect-porcelain, blonde-bobbed Mortie hums along, in song.

Jess Day is also a darling girl. She never stops smiling. She never stops singing. She wears bright little flats and bright little dresses. Like Mortie, we do not know where she comes from. Nor do we know where she goes.

They sure are cute, these bright-eyed gals. They convince us that we like them without doing much at all. Darling Mortie has lived on the Morton Salt cylinders forever. Jess on the other hand, is supposedly a leading lady. Played by Zooey Deschanel, she is the heroine of Fox’s sitcom New Girl. Jess Day is certainly spunky, and yet, after the past six episodes, that seems to be all we know. For a show that some critics have lauded as the best new sitcom on television, Jess is a stunted character that too closely resembles her two-dimensional salt-box counterpart.

The premise of New Girl is simple. After discovering that her boyfriend is cheating, Jess moves her bespectacled, doe-eyed broken heart in with three dudes she finds on Craigslist. She’s zany, requires constant attention, and looks cute when she cries. As Jess wreaks girlie-quirk havoc on the dudes, focus-group-tested hilarity ensues. The show has its laughable moments, but most episodes are 20-minute cringefests. My primary problem with New Girl is not Jess’s other-dimensional, spaced-out personality. It’s the fact that we don’t know why it’s a part of her. Actually, we know surprisingly little about Jess at all.

That’s not entirely true. Right away, we learn that Jess is a girl of many quirks. She love, love, loooooves to sing. She carries a talking stick. She never tones down a timbre that connotes a pretty girl’s Steve Urkel impression. Regarding her breakup, she tells the guys, “I’m a little emotional right now, so I’ll probably be watching Dirty Dancing six or seven times. A day.” Getting angry or confronting her tool of an ex-boyfriend won’t help. Instead, Patrick Swayze and the infectious beats of ’80s tunes quell her woes. The roomies smirk and shrug. No one cares that Jess’s behavior consistently flirts with the edge of psychosis. After all, “Boys will be boys. Jess will be Jess,” suggest the advertisements. Despite her unfortunate situation, Jess stoically plunders through each episode on her singular ability to remain “simply adorkable.” Thank goodness.

It’s nonsensical. How did someone acquire so many quirks in the first place? Take away the funky glasses, colorful dresses, and bursts of song, and Jess Day ends up having more in common with a naked paper doll than her TV-sitcom predecessors or viewers.

While sitcoms generally lack the narrative space to pad characters with substantial histories, Jess truly seems to have appeared out of thin air. That she’s clueless isn’t the issue. She’s blank. And until the fourth episode, when the show’s rating’s plummeted by 19 percent, blank seemed to be what viewers liked.

There’s a term for girls like Jess. She is what Bailey Doogan calls a “Logo Girl.” Ten years ago, Doogan, an American artist, wrote of her experience creating Mortie, who, after numerous tweaks and Frankensteinian adjustments, “ended up with the requisite cuteness” to fall in line with the other little logo girls we inexplicably know, love, and tattoo on our arms. Logo girls like Mortie or the Coppertone Sun Tan Lotion Girl represent the “small, cute, and plucky” tendencies in the grown-ups who buy the products. They possess “a guilelessness bordering on consciousness, an unconsciousness bordering on stupidity.”

If Mortie could talk, Doogan writes in an essay about logo girls, the umbrella’d cutie might say, “I’m strolling through a torrential downpour with an upside-down, opened, leaking box of salt, and I don’t have a clue!”

Sounds like someone else I know.

With each episode, we watch Jess flex that ever bulging quirk muscle while the sitcom’s writers neglect to define qualities that might make her a sympathetic character. Initially, viewers might relate on surface level, but how long are we expected to connect to someone by way of bangs, kooky songs, and an overplayedDirty Dancing DVD? Showing a version of Jess that is anything other than awkwardly cute is out of the question. Yet, being anything other-than-cute is exactly what she needs in order to lift off the page.

No one, for example, questions Jess’s obvious discomfort when it comes to her sex life. She releases a childlike squeal when she walks in on one housemate naked in his room. Jess wants to talk about what happened, but at the same time she refuses to say the names of sexual organs. “I accidentally saw Nick’s peepee and his bubbles,” she chirps. For someone who just broke up with a live-in boyfriend, Jess’s reaction resembles genital phobia, not humorous roommate awkwardness. By the end, penis enters her vocabulary, but Jess makes no connections to how she might grow from her past experiences. And the fact that she still refers to her vagina as a “gum-buh-bot” is just hilarious! Rather than illuminating a complicated and potentially compelling hang-up about sex and guys, Jess’s quirks remain the cause and excuse for all of her behavior.

In its first six episodes, New Girl reveals one detail about Jess that sheds light on who she is as a person. Jess Day is a teacher. Of what, we don’t know, but it might explain why she talks like a whiny child to the grown-ups in her life. Her bashfulness towards sexuality could be a result of teaching students all day. Still, it’s difficult to believe that Jess manages a classroom full of kids when she relies on her roommates and friends to take care of her. Cece—her hot, model BFF—plays the role of Jess’s mother, offering her friend constant tokens of model wisdom and outfits. When Jess gets a date, Cece doesn’t wait for the call; she knows to come over because silly Jess can’t dress herself. How adorable.

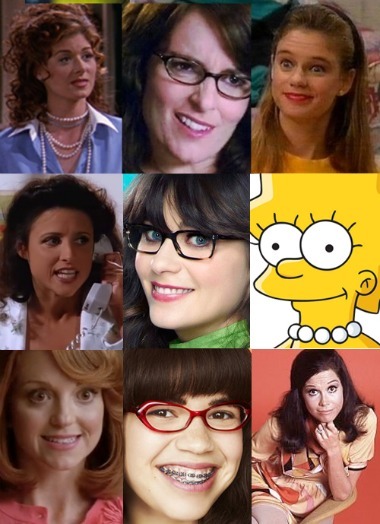

But it doesn’t add up, for the simple fact that TV girls like Jess, who are this clueless in all of life’s intricacies, do not have hair that looks that good. At least those other TV girls develop. Prime time has had its share of truly hilarious female supporting and leading ladies who exude varying degrees of weirdness. But oddball riffs are just one aspect of their character development. Jess Day’s one-sided personality relies on an assortment of quirks, which causes New Girl to fail at fostering a game-changing leading nerdy girl.

Iconic logos do not appear from thin air. They have histories, and the logo you see at any given moment is probably not how it began. A timeline of Starbucks logos visualizes the brand’s evolution and also the stripping away of Melusine, the twin-tailed siren who graced the original cups. Over time, the company has cropped and stylized the original, sexually powerful image so that it no longer connotes mythology but instead evokes instant craving. She becomes asexual without losing the lust factor.

The idea translates quite well to television. Doogan writes, “Point of purchase has moved off the shelves and become the logo incarnate. We know them. We crave them. The more we consume them, the more they waste away.” The real-life woman who plays Jess has made a business of cultivating oddities to the point where quirkiness is a quantifiable measure of uniqueness. New Girl—along with Zooey Deschanel’s recent media venture, Hello Giggles, and a Twitter feed set to constant quirky-hiccup mode—works as a convenient storefront for broadcasting a logo of her own.

Despite the fact that Deschanel has said she identifies with the character, Jess is not a logo girl for the actress. Deschanel may say some weird shit, but history tells us the writer-singer-actress-publisher-feminine-feminist is a talented eccentric whose quirks have carved her a place in Hollywood. However, the reasons behind Jess Day’s idiosyncrasies are subordinate to how she or show’s writers choose to visually represent them. Her cabinet of quirky curiosities is a commodity that serves as an acceptable substitute for originality.

Without her own history (despite the show’s few contextless flashbacks to an adolescent but equally zany Jess; we don’t know where she comes from or even how her quirks transpired), Jess Day cannot be an original character. Nor does she fit the mold of a Manic Pixie Dream Girl; unlike MPDGs (another Zooey speciality), Jess’s story doesn’t support the development of the dudes in her life. She exists to be the supported, yet the attention from others amounts to little in her depth of character. If she represents commoditized twee-weirdness, she must be the accepted substitute for something else.

But what—or whom—does she replace? She had to come from somewhere. The question of where is actually posed in New Girl’s title song, written by Deschanel,who cites The Mary Tyler Moore Show as inspiration. But Jess isn’t quite the stripped-down substitute for Mary Richards, a favorite of feminist TV junkies.

“Who’s that girl?” croons our character. “Who’s that girl?”

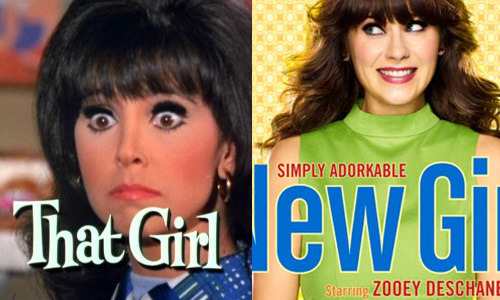

That girl is actually, well, That Girl. The American sitcom aired in 1966 and starred Marlo Thomas as Ann Marie, a fresh-faced and, yes, quirky young lady who set off on her own for the big city. That Girl was the first sitcom to feature a young woman who wasn’t married or living at home. Like Jess, she’s bubbly, brunette, and bright-eyed. In the title credits, we recognize the early sign-offs of our own little Logo Girl. Finally, Jess’s backstory begins to make sense.

Diamonds, daisies, snowflakes, / that girl / chestnuts, rainbows, springtime… / is that girl / she’s tinsel on a tree… / She’s everything that every girl should be!

Even That Girl’s theme song begins to put an original idea to the commoditization of Jess’s character. All she needs is a list of things she loves to make her who she is. Where she’s planted or where she grows is secondary to the sparkly tinsel that ices her branches.

That Girl was the first attempt to make sense of what mattered to us plucky independent gals. It almost seems forgivable that quantifiable quirks played into Ann Marie’s character, especially since viewers could at least gather that she had ambitions. Unlike Jess, Ann Marie lived with her boyfriend. Not entirely in step with today’s standards, but who’s the stronger leading lady? An adorable go-getter who lives with the boyfriend, or a stunted, twee girl-woman who depends on three guys for attention and emotional support?

In the chapter “How to Write Sitcom Characters” in Jurgen Wolff’s Successful Sitcom Writing, the first question Wolff asks is “What does the character want out of life?” That Girl wanted to make it as an actress in the Big Apple. For a single gal in 1966, she set her ambitions high and followed through. But what is Jess’s goal? In a recent episode, Jess invites her coworker-crush to Thanksgiving and reveals—finally—a tangible desire: “I want to have sex with him big time,” she shouts. “I want to take him down to Chinatown and slice him off a piece off this pumpkin pie.” How modern.

For a 21st century character, Jess is completely dependent on others perhaps because she doesn’t have a history of her own from which she can draw. This makes Jess Day today’s ironically ideal substitute for That Girl’s Ann Marie. The adorable and dorky girl—ambitions included—existed 45 years ago. But just like Mortie, Melusine, and the other logo girls, her depth has eroded. Commoditized quirkiness through FOX’s compound-word choice of qualities now suffices for real character. She’s a purely visual representation of a role that might have once been a little bit innovative. That Girl laid the foundation that has enabled New Girl to function as an acceptable substitute for substance. But weird for weird’s sake isn’t compelling. It isn’t feminine. And it isn’t feminism. It’s embarrassing.

Jess’s inability to self-actualize may not be Zooey’s fault. But perhaps the single reason New Girl has done well is that we are happy to spend 22 minutes each week watching one Logo Girl play another. In addition to voicing certain carnal urges in the Thanksgiving episode, Jess uses her body warmth to defrost a frozen turkey. At the core, viewers aren’t tuning in to be entertained by Jess’s bizarre behavior. They’ve come to watch Zooey thaw a turkey. In a Q&A before the show’s premiere, Deschanel said, “I like that [Jess] is completely herself and unabashedly emotional, but not in an obnoxious way.” Only, Jess is not emotional; she’s stunted by her single quality. And it is obnoxious.

While New Girl’s ratings are down from the first few episodes, the show still holds the attention of the 18-to-40 crowd. Admittedly, I’ll continue to pay $2.99 to download more episodes on iTunes. I’m not, however, watching for Zooey. I’m hoping for a Jess with substantial desire, and a little depth wouldn’t hurt. But with the introduction of her new love interest—Justin Long dressed up in a comparable grab bag of unexplained weirdness—I’m not holding my breath.