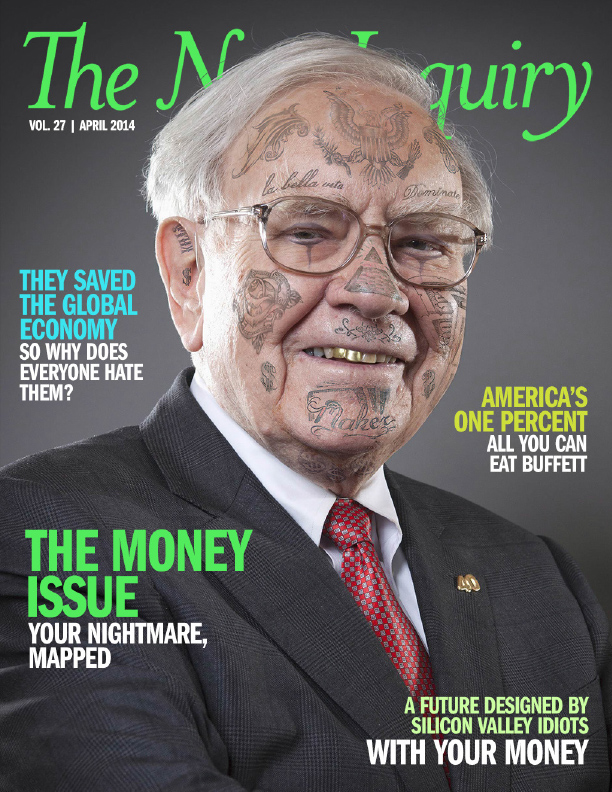

Money

Editors' Note

Money: free for those who can afford it, very expensive for those who can’t. The purported measure of all things and the most powerful of our mass delusions, money is imaginary and unlimited, as any central banker will tell you. And yet that never seems to help anyone get their hands on enough of it. Nowhere is the contradiction between something being a socially constructed fiction and material determinant of the world around us so strong as it is in a dollar bill. It’s obviously fake and yet oh so real.

This contradiction wasn’t always so extreme: In 1896, William Jennings Bryan propelled himself to presidential nominee purely through an impassioned convention speech likening the gold standard, the original austerity policy, to a “crown of thorns” being pressed down on the “brow of labor.” But in the ensuing century, the idea of a monetary policy open to populist debate and democratic control has become a joke, swinging from a lived reality at the turn of the 20th century to a weirdo fringe in the 21st screaming “End the Fed.”

In the fallout from the 2008 crisis, that fringe has been moving toward the center. From Modern Monetary Theorists arguing that fiat money emerges from the policeman’s truncheon to Glenn Beck–inspired gold bugs stacking bullion in their air-raid shelters, money itself, and not just its distribution, is once again a prominent object of contention. The premise of the end of history was that money had finally won out over politics—but the crisis required a hell of a lot of politics to shore up the monetary system.

So what is money? Is it the true innovation of statecraft, the thing that enables and justifies coercion through taxation, as Rebecca Rojer notes in her account of MMT? Is it financial engineering’s raw material, or its necessary fiction? Is it a claim on future production, or does it warp the future by dragging it into the present? Is it a social construction that delinks debt from reciprocal social obligations, making industrialization, massive urbanism, alienation, and possessive individualism possible? Is the beginning or the end of trust? Does it remake quality as quantity, and substitute insecurity and artificial scarcity for natural satiety? Is it the root of all evil, or the solution to all of our problems? Should we redistribute it or abolish it? Can we have some?

Money doesn’t grow on trees, we’re told, but it does grow in bodies. Moira Donegan takes us through the world of paid surrogates in “Over Easy,” where it turns out it’s not good enough to be fertile. To sell your eggs you have to sell yourself as a success first and amass human capital. Mike Konczal details how human capital has a future in the futures market, in which the lives of graduates might be subject to the same sorts of detailed scrutiny and specification as a delivery of pork bellies. Jason Huff looks at Amazon’s MTurk service, labor clearinghouse for microtasks in which workers are treated as largely interchangeable and human capital becomes negligible, if not extinguished.

The fate of human capital in crowdsourced labor markets may mirror the fate of capital itself in what Izabella Kaminska describes as an increasingly “postcapital world,” in which the overabundance of capital demands alternative approaches to investment and industrial policy, with China leading the way. In “The Paper Chase,” Rob Trump tours the history of American alternative currencies, finding that the value of value can shift with a system’s, well, values. In “Disgorge the Cash,” J.W. Mason argues that the financial sector isn’t about putting value into the economy but extracting it. And that no matter how difficult radical struggles are, he argues, it’s nothing compared to “the Sisyphean task faced by the other side, of constantly transforming the existing organization of production into capitalism.” Money is a boulder that never stops rolling down the mountain. It flattens everyone and everything.

Money is often mistaken for liberty, when it typically functions as a mechanism of control. Steve Randy Waldman considers its role in linking capitalism to freedom, arguing that the purpose of markets is to nurture illusions of political choice and depersonalizing the behavioral limits we place on one another. But of all the illusions sustained by money, perhaps the most dangerous is that everything should have a price, even the privilege of being not for sale.

Featuring

-

Vol. 27 Editors' Note: Money

-

Disgorge the Cash

-

M and A

-

The Postcapital Economy

-

Buying the Future

-

No Choice but Freedom

-

The World According to Modern Monetary Theory

-

The Paper Chase

-

Over Easy

-

No Purchase Necessary

-

Serf Boards

-

We Have Met the Enemy